by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Mar 30, 2023 | Management Methods

Jim Rogala

The intense transfer of materials within a tree at this time of the year makes for efficient girdling. Girdling is simply the removal of the “bark” to kill a tree. I use girdling as my go-to method for killing aspens clones. The method works best on clones where stems are at least an inch or two, although it can be used in combination with double cutting of the smaller stems (a topic for another post). It is critical to girdle all stems of a clone. I use it on a number of other species, including birch, but it doesn’t work on all species (e.g., box elder).

The key to successful girdling without using herbicide is to remove the outer layers (inner and outer bark) of the truck without injuring the innermost parts. I’ll bore you with the plant anatomy and physiology details in a later paragraph, but the details are really unneeded to accomplish the mission at this time of year. There is an obvious break between these layers when the tree is translocating a lot of materials upward, which is happening now. A person can simply run a tool between these layers around the entire circumference with a span of at least 6 inches wide. There’s no need to have clean cuts on the upper and lower ends of the separation, with the end-product often being somewhat banana-peeled looking.

There are a variety of tools that can be used to girdle, but from the description of the process above it’s obvious that a chainsaw is not one of them. For smaller trees, I often use a somewhat dull wide-bladed wood chisel. For larger trees, I use a flat pry-bar or a leaf spring cut to a manageable size and sharpened on one end. First I use the tool vertically to open an area to access the location between the layers, but this should be done without cutting too deeply into the tree. Then, put the tool between the layers horizontally and work it around the tree.

For those of you that are curious, here’s why this method works. There is a lot of specificity in the cells of a tree. There are those that transport materials upward in the inner layers (the xylem), and those that transport materials downward in the outer layer (phloem). Products stored in the roots, along with water, are sent upward. Products generated by photosynthesis in the leaves are sent downward. By removing the outer layer, the plant starves to death without the translocation of nutrients to the roots. You might be thinking that just cutting the tree might serve the same purpose. Well, that’s true for some species (such as cedars), but most trees have a strategy that includes resprouting from the base (or, like aspen, from rhizomes) when the xylem is disturbed. Be patient when looking for the results, as the tree will appear fine until the need for nutrients from the roots becomes great in the following spring. Sometimes it might take two years for the tree to die.

More information on girdling can be found by searching the web, but be careful to look for methods similar to what I’ve described here that don’t use herbicide. Tom Brock has a section on this topic on the Pleasant Valley Conservancy website (http://pleasantvalleyconservancy.org/brushandtrees.html). This method is not only effective, but minimizes the use of herbicides, which is attractive to me.

by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Oct 4, 2022 | Management Methods

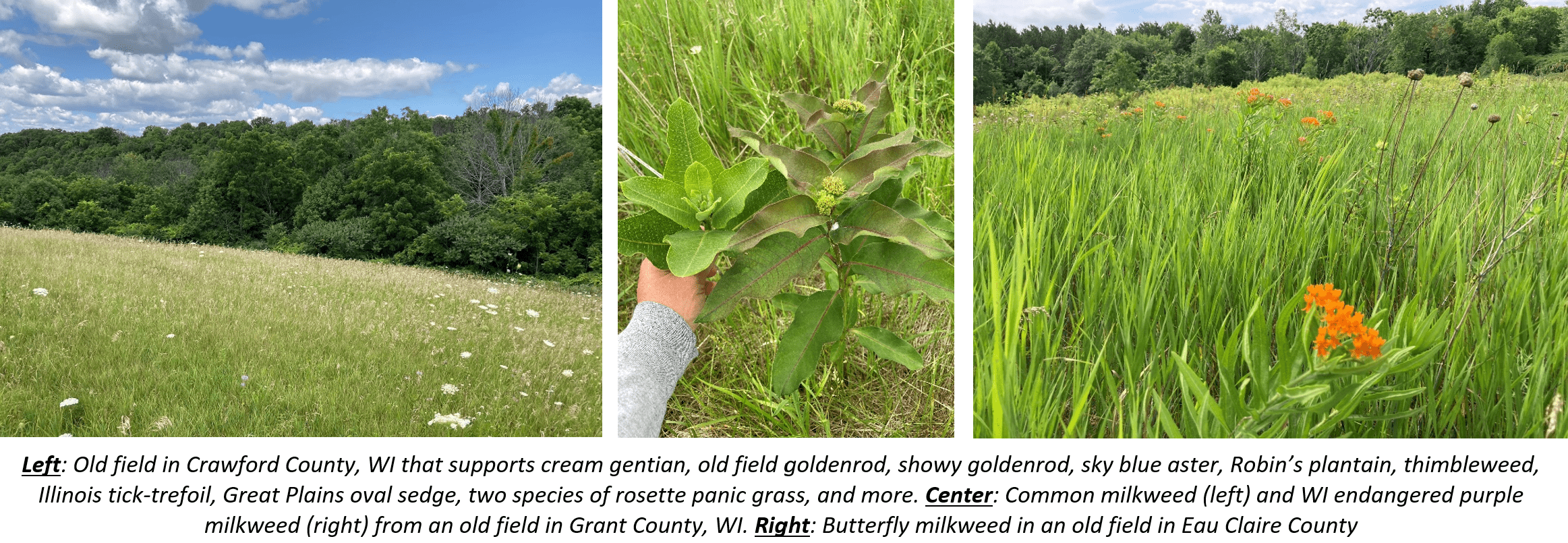

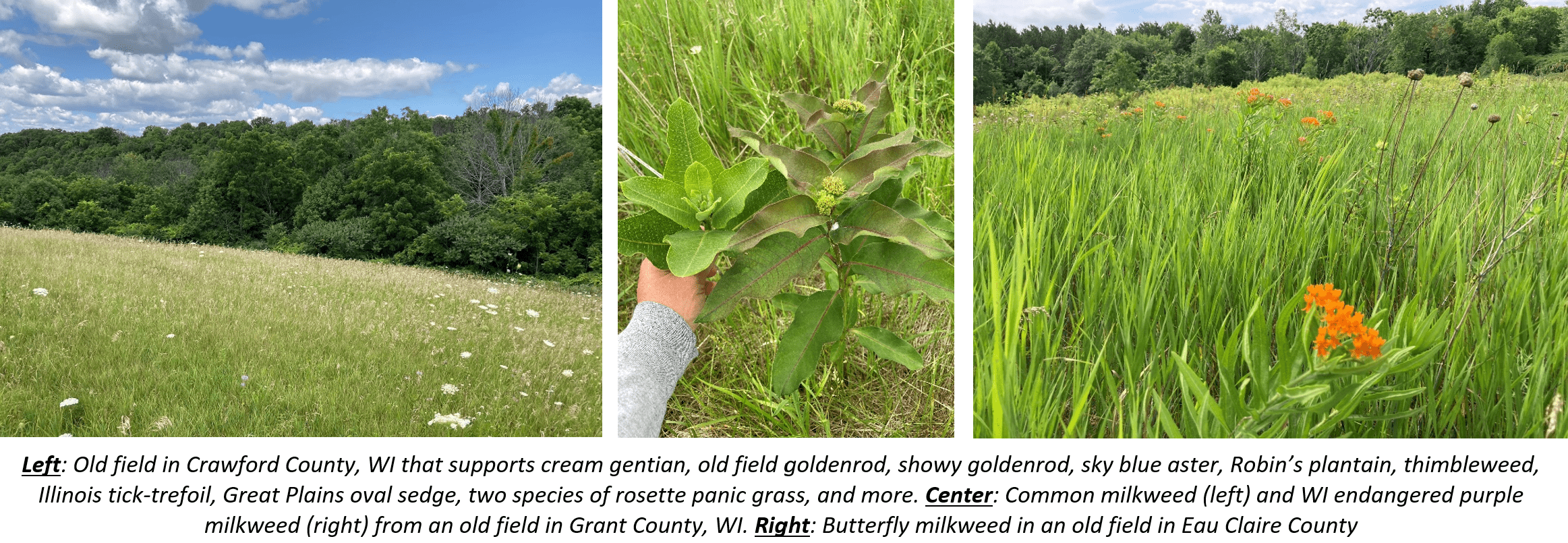

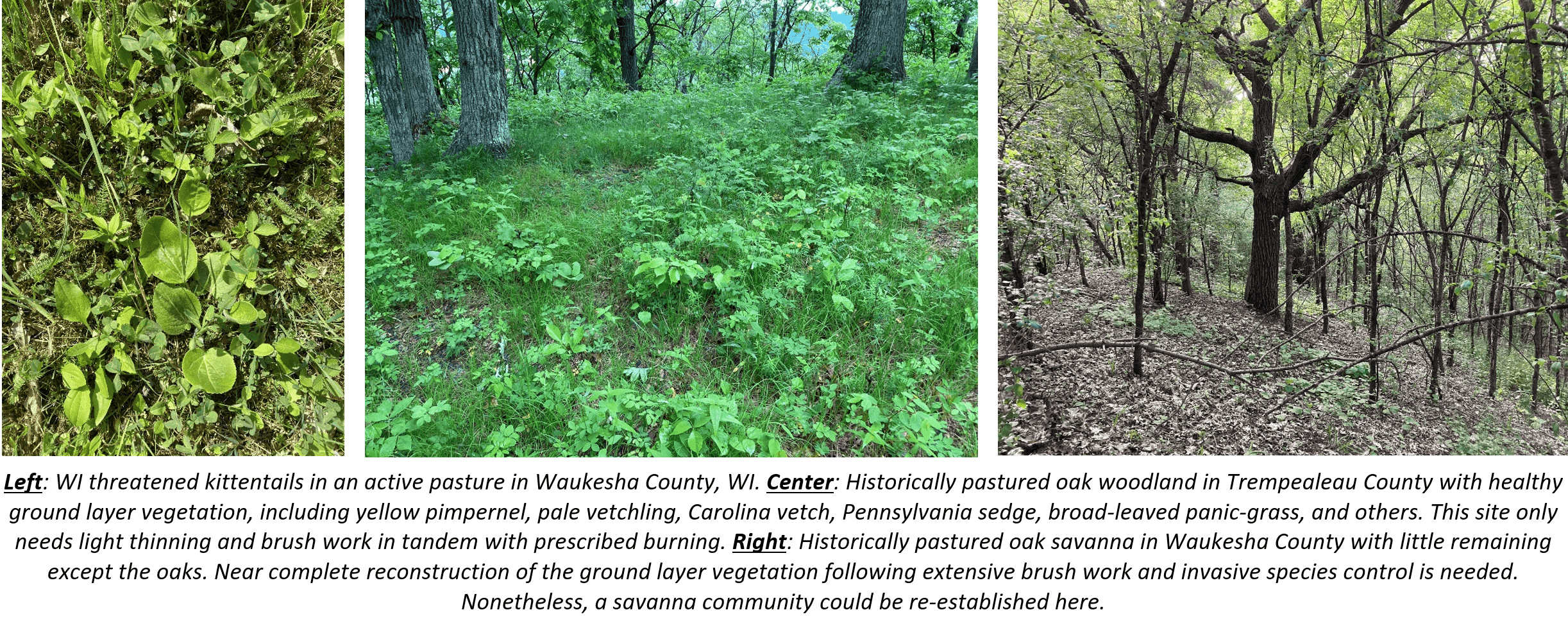

If you have an old field that you would like to plant to prairie or a stand of oak you would like to restore, don’t rush into it. Understand the history of the land and take time to observe and learn whether anything important remains. Very often degraded lands still harbor irreplaceable elements of biodiversity, and these have their own stories to tell about what a place was and could be. The tools we use in restoration can encourage these elements or extinguish them. By recognizing and preserving remnant populations of native species and their genes, we can counteract biotic homogenization[i], and sometimes we can reduce project complexity and expense in the process.

Many landowners with prairie planting projects in old fields or retired pastures already have important elements of the biodiversity they are trying to restore, many of which are commercially unavailable. Occasionally remnant populations of rare plants persist. Even areas that were formerly cultivated often support good prairie, savanna, and oak woodland species that have recolonized from the edges, or perhaps a neighboring oak savanna that has since become forest. In many cases as many desirable native species remain as would be required for a seed mix planted under a cost-share program! I have included a table with upland species often encountered in old fields and pastures; there are many more. It is not uncommon to encounter five to fifteen of these species in an old field and ten to twenty of them in a retired pasture.

In cases where there are some good things present, start by managing these areas as though they were still prairie. Selectively control encroaching woody vegetation and any patches of broad-leaved herbaceous weeds. Burn for a couple consecutive years during the dormant season to encourage anything good that might be suppressed by the thatch. See what happens and go from there, which will usually mean integrating inter-seeding, a lot of burning, and patience.

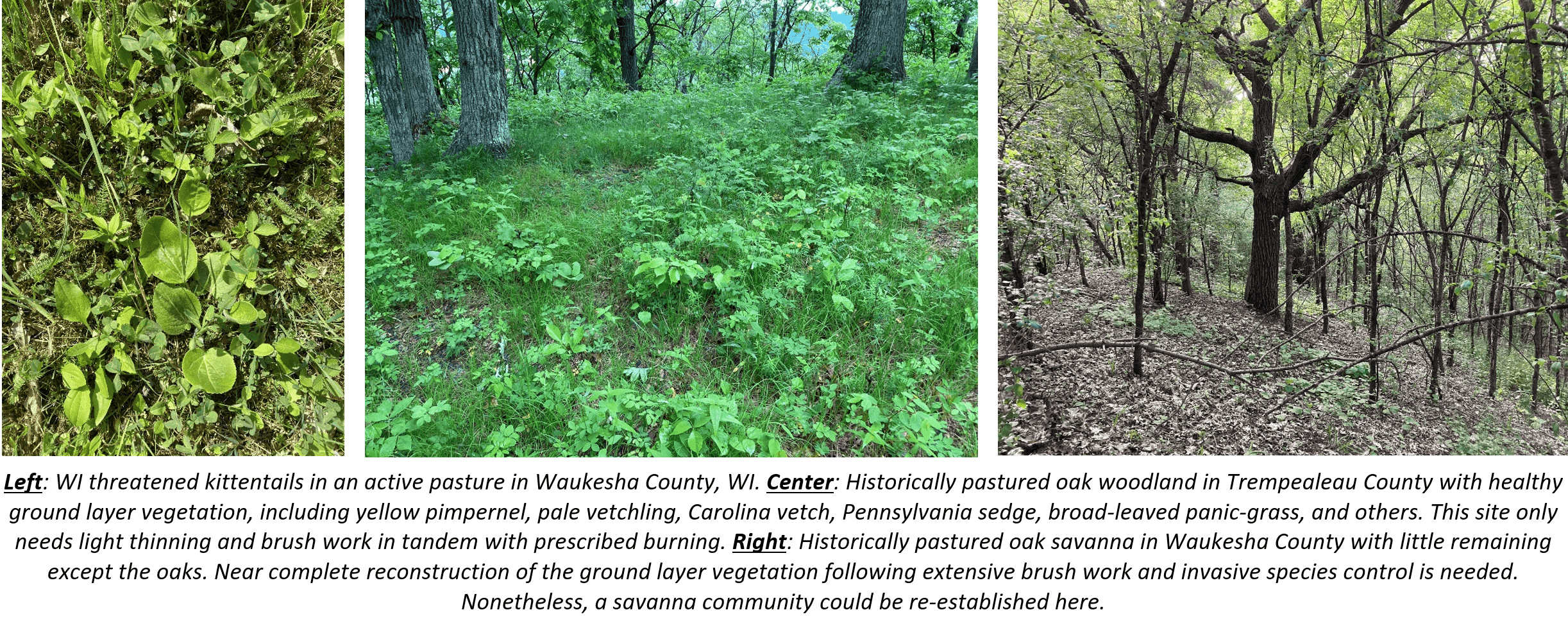

Many landowners with wooded ground have land that was once oak woodland, oak savanna, or oak barrens. Oak woodlands are conservation-worthy and rare, but they are sometimes mistaken for forests or inappropriately treated as savannas[i] or barrens. It is far more common to encounter structurally intact ground layer vegetation in heretofore unrestored woodlands than open savannas. In oak woodlands, good cover of Pennsylvania sedge or dry-spiked sedge often remains, and species that tend to favor dappled light vs. deep shade or full sun—poke milkweed, pale vetchling, yellow pimpernel, broad-leaved panic-grass, bearded shorthusk, purple Joe-pye weed, Carolina vetch, etcetera—are often still present. Even where oak woodlands have become shadier, that change has usually been more gradual and less in degree than in savannas. This has allowed more of the woodland vegetation to hang on. Where a low sedgy or grassy ground layer remains, restoration might only involve modest brush work, removal non-oak understory hardwoods, non-oak overstory thinning/girdling, restoration of fire, and modest inter-seeding of missing species over time. Savanna restoration is critically important where true opportunities still exist, but good opportunities to restore oak woodland seem to be more common than savanna.

If you have an open area of cool-season grass or a stand of oak, I encourage you to take a closer look. You might discover there is more opportunity, or a different opportunity, than you initially thought. If you are looking for cost-share, go shopping for assistance that helps to build on what remains. Doing so should result in projects that conserve more community, species, and genetic diversity on the landscape.

Rich Henderson’s presentation “Converting Pasture to Prairie” on YouTube is an excellent resource.

______

i- Biotic homogenization is the process by which spatially separate ecological communities become more similar over time as the result of extinctions and invasions (or introductions).

ii- I use ‘savanna’ here in place of ‘oak opening’ for relatively open communities with mostly widely spaced, open-grown oak trees with prairie vegetation in-between.

______

| Species |

Common Name and Notes |

| Andropogon gerardii |

Big bluestem |

| Antenneria spp. |

Pussytoes |

| Aristida spp. |

Three-awn grasses |

| Asclepias amplexicaulis |

Clasping-leaf milkweed, sandy sites |

| Asclepias syriaca |

Common milkweed |

| Asclepias tuberosa |

Butterfly milkweed, sandy sites |

| Asclepias verticillata |

Whorled milkweed |

| Besseya bullii |

Kittentails, P |

| Bouteloua spp. |

Gramma grasses, P |

| Carex brevior |

Great Plains oval sedge |

| Carex gravida |

Heavy sedge |

| Carex normalis |

Greater straw sedge |

| Carex umbellata |

Parasol sedge |

| Cirsium discolor |

Prairie thistle |

| Crocanthemum spp. |

Frostweeds, sandy sites |

| Desmodium canadense |

Showy tick-trefoil |

| Desmodium illinoense |

Illinois tick-trefoil |

| Dichanthelium spp. |

Rosette panic-grasses |

| Erigeron pulchellus |

Robin’s plantain |

| Fragaria virginiana |

Virginia wild strawberry |

| Gentiana alba |

Cream gentian |

| Lathyrus venosus |

Veiny Pea, P |

| Lechea spp. |

Pinweeds, sandy sites |

| Lespedeza capitata |

Round-headed bushclover |

| Lithospermum caroliniense |

Hairy puccoon, sandy sites |

| Lobelia spicata |

Pale-spiked lobelia, P |

| Lysimachia lanceolata |

Lance-leaved loosestrife, sandy sites |

| Monarda fistulosa |

Bergamot |

| Oenothera perennis |

Small sundrops, P |

| Packera paupercula |

Balsam ragwort, P |

| Penstemon gracilis |

Lilac beardtongue, sandy sites |

| Primula meadia |

Midland shooting star, P |

| Pycnanthemum virginianum |

Mountain mint |

| Ranunculus fascicularis |

Early buttercup, P |

| Ratibida pinnata |

Yellow coneflower |

| Rudbeckia hirta |

Black-eyed Susan |

| Schizachyrium scoparium |

Little bluestem |

| Solidago juncea |

Early goldenrod |

| Solidago nemoralis |

Old field goldenrod |

| Solidago rigida |

Stiff goldenrod |

| Solidago speciosa |

Showy goldenrod |

| Sorghastrum nutans |

Indiangrass |

| Symphyotrichum oolentangiense |

Sky-blue aster, P |

| Tradescantia ohiensis |

Ohio spiderwort |

| Verbena stricta |

Hoary vervain |

| Viola sagittata |

Arrow-leaved violet |

‘P’ used for species more often found in pastures than old fields

[i] I use ‘savanna’ here in place of ‘oak opening’ for relatively open communities with mostly widely spaced, open-grown oak trees with prairie vegetation in-between.

by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Mar 26, 2021 | Management Methods

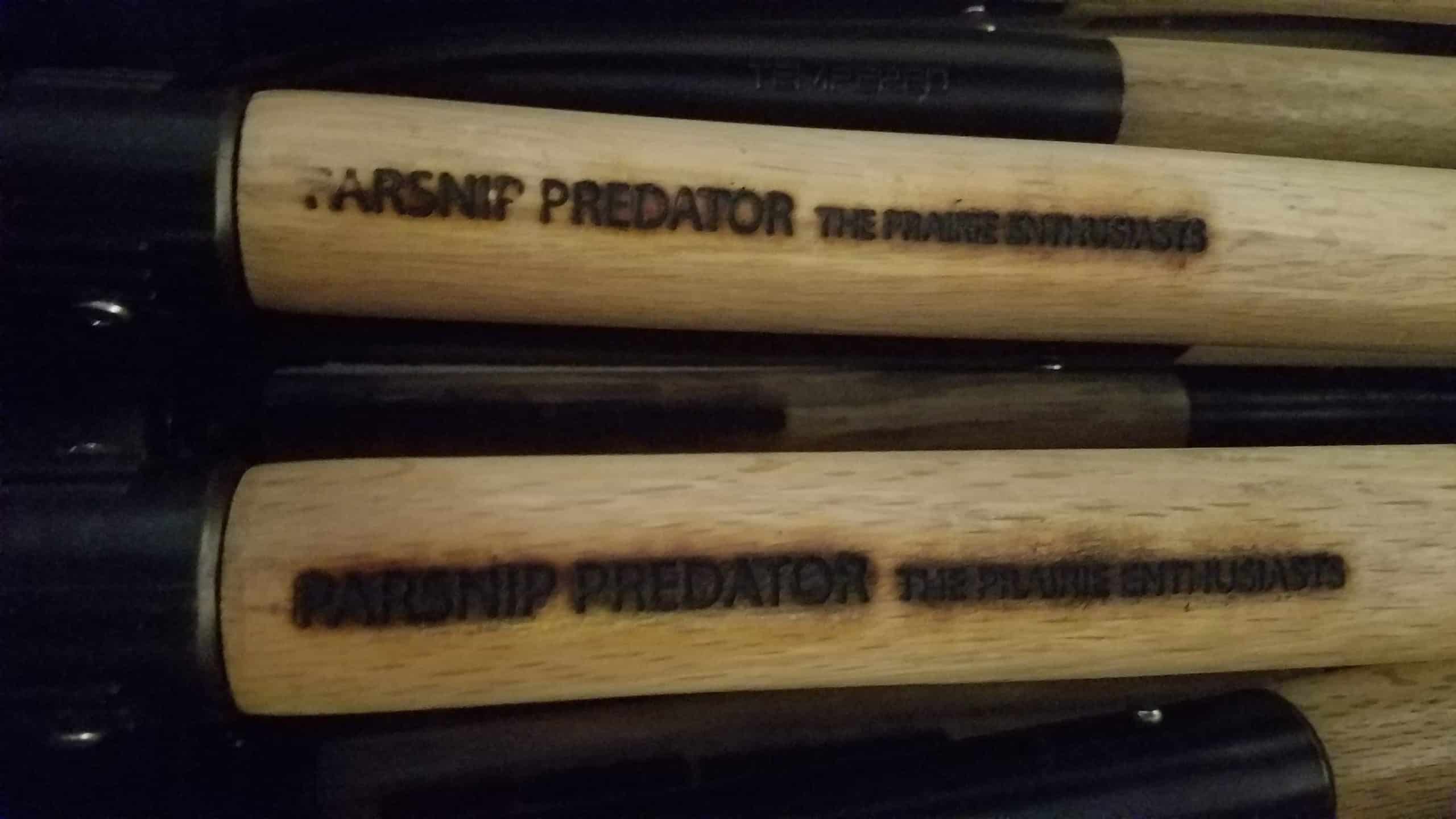

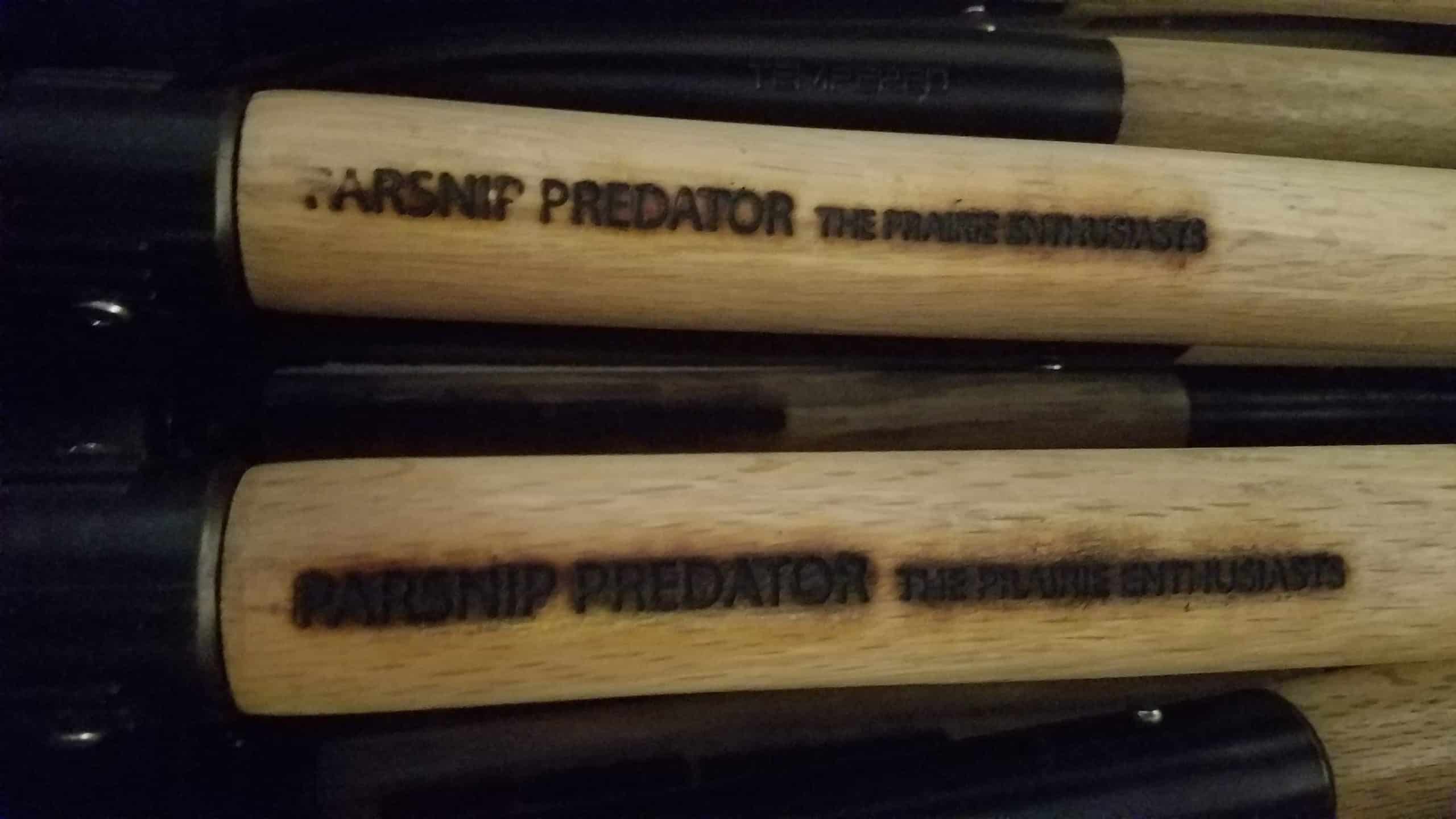

If you’re not familiar with the Parsnip Predator, you’re missing out!

Invented and produced by members of TPE’s Prairie Bluff Chapter, the Parsnip Predator is a tool designed for prairie invaders like wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) and burdock (Arctium minus). It has gone through a few changes over the years, but it’s still just as useful for tackling taproots.

Now’s the time to “gear up” for another season of restoring healthy prairies. Visit our eStore and get your own Predator in time for the first wave of parsnip!

Thanks to TPE volunteer Nick Faessler for the use of his workshop to create these useful tools, and for these photos showing the process.

Volunteer Gary Kleppe sharpens the notched blade of a Predator.

Once the Predators are branded, they’re ready to go!

by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Nov 19, 2020 | Management Methods

This article was a collaboration with Jeb Barzen.

Interested in pitching in to save our fire-dependent ecosystems? TPE’s next prescribed burn crew training will be an online-only class on February 23, 2021 (the day before our TPE Online Conference). Instructors Rob Baller, Scott Fulton, and Andy Sleger from the Empire-Sauk Chapter will lead this all-day event. Visit the conference page to learn more.

—–

More fire safely — and effectively — on the ground.

That’s the wish of educator and Wisconsin Prescribed Fire Council member Jeb Barzen. “In Wisconsin we are currently burning 5-10% of our fire-adapted communities that require periodic fire management,” notes Jeb, who is also a site steward for TPE. “The longevity of these remnant ecosystems, that intelligent tinkerers wish to save, is vanishing. Concurrently, we have more landowners (both private and public) that want burning to be done than we have resources to respond.”

To develop more trained fire ecologists, Jeb and co-instructors Rob Nurre, Rob Baller, and Scott Fulton have organized a series of annual prescribed burn classes over the last five years. This year, TPE’s Prairie Sands Chapter sponsored two basic burn training sessions in October and November. Despite the unusual circumstances, both classes were a success.

Each class was held outside and followed TPE’s guidelines for events during COVID-19. Class sizes were limited to eight masked students representing a range of ages and backgrounds. The students took notes from lawn chairs spaced apart in the grass while the instructors taught at a distance, using a whiteboard to diagram burn scenarios. Interspersed with these lectures were field explorations of how fuel types relate to fire behavior and weather. Whether or not the weather would allow actual fire was a lesson in itself.

Outdoor lecture. Photo by Rob Baller

Friends and members of TPE generously offered the use of their private properties for these classes. The October 31 class convened at Cassell Savanna in Sauk County. On this cold and windy Halloween day, the students wore thick hats and long underwear. By the time the second class (at Prairie Hill Farm in Marquette County) rolled around a week later, the weather had changed to 70°F with all sunshine.

Field training at Cassell Savanna. Photo by Rob Baller

Despite the difference in temperature, both weekends were made more complicated by high winds. Live fire was at a minimum; only the students in the second class could practice burning breaks, and only in the shelter of the woods. Even so, the students remained engaged, socially distant, and open to the lessons that these conditions provided. Students later described the class as “interesting, engaging, enjoyable” and even “the best of the [burn classes] that I’ve taken”.

Nevertheless, two small classes alone won’t solve the problems facing fire ecologists. More frequent and widespread training is required. “Just a few unsafe fires can greatly inhibit our overall ability to burn because the public will not support risky ventures,” Jeb observes. “Ineffective fires also waste limited resources that we can ill-afford to squander… Sponsors of prescribed burn courses provide both fire practitioners and pyroecologists the very basis necessary to succeed at conservation. We need to do more.”

Field training at Prairie Hill Farm. Photo by Rob Baller