Who We AreSylvie Rising Operations Assistant...

Catching the Prairie Bug

Catching the Prairie Bug!

Photos and Story by Jonathan Rigden

This story was featured as a guest column in The La Crosse Tribune.

Zoerb Prairie in Hixon Forest in August with rough blazing star blooming in the foreground.

Do you know that prairies and oak savannas once filled much of the landscape in western Wisconsin and that only a tiny fraction remains? And that this tiny fraction is disappearing fast? Some readers may have heard of a group called The Prairie Enthusiasts. This organization is a nonprofit land trust that has chapters in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Illinois and works throughout the tristate area to save as many of these relics from the past as possible. In doing so, we hope to preserve and grow this unique ecosystem that supports an abundance of special plants and animals. The Coulee Region Chapter of the Prairie Enthusiasts includes the counties of La Crosse, Vernon, Monroe, Buffalo, Trempealeau, and Jackson.

A prairie can escape the attention of those who have never been exposed to and noticed its wonders. But something out of the blue can spark an interest, like seeing a beautiful prairie flower for the first time or colorful bees hovering over a native thistle. Then, some susceptible individuals “catch the prairie bug” and a cycle begins. They identify the flower and one of the bees. On the next hike, they see another amazing flower with a delicate butterfly feeding on its nectar, look them up, and there you have it, they’re hooked! A cascade is launched- interest leads to learning leads to knowledge leads to more interest, learning, and knowledge and so on. And a fun-filled adventure awaits!

But all the beauty of the flowers, grasses, insects, birds, and other critters on the prairie can escape our interest without a spark. Like the fires that keep the prairies healthy, something must start this process. Fire is said to need three components to become self-perpetuating- fuel, oxygen, and heat. But you can have all the fuel, oxygen, and heat in the world and there won’t be a fire until a spark ignites the system. Our hikes, work events, and educational programs might be just the spark needed to set the your cycle in motion and, as we say, “Ignites your relationship with the land”!

Many of you might have noticed the cleared and sometimes burned areas on some of the bluffs in our area, including in Hixon Forest. The Coulee Region Chapter has been involved in many of these efforts while teaming up with other groups such as Friends of the Blufflands, the Mississippi Valley Conservancy, and the Wisconsin DNR. Despite this significant progress, there is still much to be done. Many bluff prairies in the Driftless Area continue to be taken over by red cedars or invasive nonnative plants like buckthorn. In a perfect “prairie world” all of these sites would be saved. That, of course, is unrealistic, but many can and should be saved before they are gone forever. This restoration and maintenance work could come from landowners, contractors, and volunteers but the effort needs to be guided and coordinated. In our six-county area, we hope that the Coulee Region Chapter can help lead this effort.

So, as a new year begins and some of us think about our goals, perhaps one of them could be getting out, investigating the prairies near you, catching the prairie bug, and supporting the Coulee Region Chapter of The Prairie Enthusiasts by becoming a member and volunteering on our work days. Check out our chapter HERE and follow us on Facebook.

Happy New Year!

We All Have Mentors

We All Have Mentors

By Scott Weber

November 13, 2023

I was introduced to the prairie project in the spring of 1979 by volunteering for a burn. Back then, we had no burn permit, no official burn plan, and no equipment other than matches, rakes, water jugs, and wet burlap to use as fire swatters, but we did have a general notion of backfires and head-fires and which one to light first. By summer of 1979, the project consisted of two seed plots, 1978 and 1979 spring plantings about an acre a piece, plus the sod transplant area of much smaller size. Konrad graduated in spring of 1978, as did many of the student volunteers, so we were very dependent on the help of Dr. Jensen and Konrad’s thesis. I also checked out The North American Prairie, by Dr. John Weaver, and tried to use that to identify the grasses in the new prairie, not realizing that most of it was still brome grass. That is a revelation that most of us have had at some point: virtually all of the vegetation on our roadsides and farmland is not native to North America. Suddenly every prairie remnant, from McKnight to the big bluestem along the railroad right of way, was precious.

A geology professor, Dr. Ed Buchwald, became the first Arboretum Director and began hiring two to three students in the summer as Arboretum assistants in 1978, and I jumped at the opportunity to work in the Arboretum with my coworker, Dick Mertens, for the summer of 1979. We repaired the trail network from the erosion caused by runoff from the fields the college rented out but also pulled parsnip in the postage stamp prairie remnants, collected seeds for future plantings, watered transplants, and did other maintenance. As far as prairie restoration went, we were greenhorns. By spring of 1980, I was the “burn boss,” having completed only one other burn in my life, and no one else was primed to take over the project, so I needed some guidance. Dr. Jensen helped us identify plants and locate seed sources, but none of us had much experience starting a prairie from scratch, so I went in search of Konrad. I needed some education from the guy who wrote the book.

Konrad returned to Wisconsin after graduation to work for the Aldo Leopold Reserve (now Aldo Leopold Foundation) to construct a pre-European settlement vegetation map of the reserve. He also worked at the nearby International Crane Foundation (ICF) planting the first seed plots on ICF’s newly purchased farm. Konrad’s friend, Charlie Luthin, convinced ICF to include habitat restoration as part of their conservation message, and Charlie planted ICF’s first prairie at their old site closer to Baraboo. A crane disease outbreak at their first site accelerated ICF’s need for a new home, and the new site was a great opportunity to do some major restoration of prairie, oak savanna, and wetlands. Our Carleton Natural History Club visited ICF in March 1980, and I asked Konrad if I could be his intern for fall of 1980.

I took the summer of 1980 off from the Arboretum job at Carleton, backpacking with my roommate in the Grand Tetons and North Cascades, and arrived at ICF in mid- August. Konrad assigned me the task of completing the herbarium collection for the site, helping his summer intern, Shelly, finish mapping the oak woodland, writing a guide to prairie seed germination and storage, and, most importantly, collecting and cleaning seed for both a fall 1980 and spring 1981 planting. Konrad kept me very busy!

Back then fall plantings were very experimental and rarely done, so Konrad was taking a big chance, especially since future funding and dedication was never guaranteed. Then, as now, speed matters, and warm season grasses and black-eyed Susans come fast in a spring planting. Fall of 1980 was a wet season, and we harvested a bumper crop of prairie dropseed and many other species from Avoca Prairie, Muralt Bluff, Spring Green and Lone Rock remnants, the UW Arboretum, and wherever else we could find seed. Fortunately, being a non-profit, we had access to seed sources normally off limits to private individuals. If we had known then what we know now, the entire five acres should have been planted in the fall, not just the one-acre plot. The dropseed and most forbs, including the gentian seed collected at Avoca, have done very well there, whereas the spring planting became dominated by tall grass. In retrospect, we wasted a lot of good dropseed and forb seed by planting most of it in the spring.

I returned to Carleton and worked in the Arboretum again in the summer of 1981 with my coworker, Sue Peterson. Armed with all the knowledge that Konrad bestowed upon us, we not only did trail repair but also sampled the 1978 and 1979 seed plots, learning that brome grass percentage will decrease with fire and competition. We collected seed for another hillside planting, and, based on Konrad’s example at ICF, turned our attention to oak savanna. Saving all the savanna oaks suddenly became a top priority. Converting crop land to prairie before government programs like the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) and government cost-sharing was difficult since the college needed the rental income, so Sue and I were free to hack away at the buckthorn and non-oak species in an opening Dr. Jensen’s students had studied and managed. That oak opening was the epicenter of the savanna project. Many thanks to Ed for letting us do that at the expense of some trail work.

We completed another seeding, about 1.5 acres, on Hillside Prairie and tilled up another acre or so to prepare for another. We contracted all the tillage work to local farmer, Palmer Fossum. Unfortunately, we didn’t have the results from the ICF fall planting, so we planted in spring. There are leadplants and other nice forbs still present after 40 years, but few, if any, dropseed or gentians in those plantings. Eventually the Arboretum Director became a full- time position with several students hired each year, but I’m not sure if Carleton would have as extensive a project as it has now without the vision and commitment of students like Konrad and professors like Paul and Ed. They deserve credit for getting the project going before the college could make a major financial investment.

Konrad also worked on other projects in Sauk County, especially the prairie along Highway 12 in front of the Badger Army Ammunition Plant as a member of the Sauk County Natural Beauty Council (SCNBC), part of a nationwide highway beautification program started by Lady Bird Johnson. After I graduated from Carleton, I worked for the Aldo Leopold Reserve, ICF, the Wisconsin Conservation Corp, and volunteered for the SCNBC board. I was either working for Konrad or following his footsteps. I learned almost every important lesson in prairie reconstruction then: the importance of good seed sources, the diversity of fall plantings, how quickly prairie species establish in nutrient poor soil, and the importance of record keeping. Konrad was also very humble; he knew that each of us is just a temporary link in a long chain of human interactions with our environment. We all have to pass the torch and move on at some point.

Unfortunately for prairies and ecological restoration, Konrad left his job with ICF to go to law school at Cornell and, soon after, moved to Seattle with his sweetheart, Karen, to gain experience in environmental law, and our paths diverged. Conservation has one of the highest education- to- pay ratios of any occupation, so law was probably the best career choice for Konrad, but not a field that I was suited for. I wanted to spend my time out on the prairie collecting seeds forever!

Meet a prairie mentor by attending one of our events! No experience necessary, and it’s a great opportunity to learn and connect with others that love the land.

Gneiss to Meet You

Gneiss to Meet You

Exploring a Rare Prairie Growing Upon Some of the World’s Oldest Rock

Story and Photos by Addeline Theis

July 25, 2023

Pulling up at the edge of a gas station parking lot in the small town of Morton, Minnesota, I had to double check if this was the correct way to enter the prairie. A small foot path leading up through hip–height sumac bushes was visible from my car. It was a sign that others before me have taken this way to view the historical outcroppings. Obviously, this was my first ever visit to Morton Outcrops Scientific Natural Area (SNA). Unknowingly, I scrambled up some boulders to find myself above the landscape, overlooking the amazing river valley. Below my hiking boots were dark slabs of granite that were covered in encroaching lichen. Finding a lichen-less portion of the rock, I noticed distinctive swirling of the pink and black bands. This was the 3.6-billion-year-old Morton Gneiss (pronounced “nice”) dry prairie that the site was preserved around.

What draws geologists into this area is the events that happened after the glaciers melted. After the Des Moines lobe of the Laurentide Ice sheet retreated from southern Minnesota and the global temperature began to rise, meltwater began to collect in large inland lakes throughout southern Canada and the northern Midwest. The largest of these lakes was ancient Lake Agassiz. Varying water levels led to the lake overflowing a moraine ice dam near present day Browns Valley, creating an outlet river. Called Glacial River Warren, this outlet river was a prehistoric river that drained Lake Agassiz between about 13,500 and 10,650 BP (Before Present) years ago. The strength and power of Glacier River Warren carved out the valley that is now known as the Minnesota River Valley.

Today the land is protected as a Scientific Natural Area (SNA) managed by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Colwell reflects:

When I was a boy, the Dakota story I heard was that the rock was the keeper of all knowledge. It had seen everything since the beginning of time, and if someone would ask in the correct way, they would learn the answer. It was almost like a library. I, of course, didn’t believe that story at the time. Once I started escorting geologists, anthropologists, and “ists” of all sorts through the site, I started to hear the same story repeatedly. The rock has seen everything since the earth cooled. If we look carefully and study hard, we will learn the answer to our questions.

Before returning to my vehicle, I took a few final moments on the ancient rocks, remembering that these rocks perhaps do have the answers to our questions. But only if we ask the right questions. I can only be thankful for the efforts of those that have contributed to the conservation and preservation of this site so that future generations can witness this library of knowledge within the Minnesota River Valley.

If you’re interested in dry prairies, visit one of our sites, like Muralt Bluff Prairie.

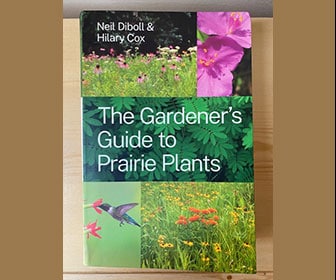

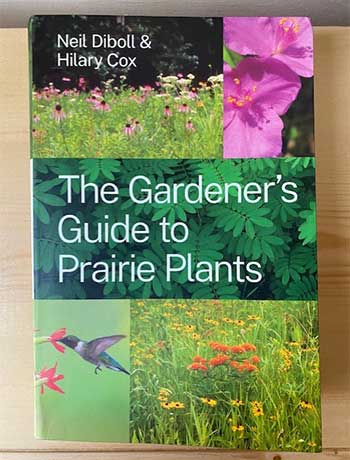

Book Review: The Gardener’s Guide to Prairie Plants

Book Review: The Gardener’s Guide to Prairie Plants

Written by Neil Diboll & Hillary Cox

Reviewed by Laurel Bennett

This 638-page book was originally intended as a field guide for identifying selected prairie species at all life stages. They certainly succeeded at that, providing extensive documentation on 145 prairie plants (18 grasses, 1 sedge and 133 forbs). But it is much more. Chapters range from “History and Ecology of the Prairie” to “The Prairie Food Web” but focus on establishing prairie gardens and ‘prairie meadows’, as the authors’ refer to a larger prairie planting, including propagating your own plants. Chapter 11 provides twelve different seed mixes for various combinations of soil types and prairie functions (butterflies, pollinators, deer resistant). Chapter 12 is stuffed with thirty more tables, covering many different parameters on prairie plants (color, height, bloom time, etc.) and some you might not even think to consider (root type, aggressiveness, groundcovers, specimen plants).

The text is necessarily short on each topic but comprehensive in its coverage of the tallgrass biome. It is ideal for the beginner interested in planting and maintaining a prairie garden or ‘prairie meadow’ but even an experienced practitioner can pick up some good pointers.

There are a number of books and blogs on propagating prairie plants, on gardening with native plants, on establishing prairies and even a few on identification of seedling prairie plants. This book stands out for its breadth of coverage.

You can find this book on Prairie Nursery’s website.

Find other interesting reads in our blog post: Our Winter Reading List

What Guides You on Your Journey?

By Scott Fulton

For thousands of years, the people who lived here shared a common set of values across diverse cultures, languages, and lifeways: a deep sense of relationship with the land and its living things, respect for all the members of that community, a desire for reciprocity and balance, and responsibility to future generations. Their active care, through fire and other means, built and maintained over time a beautifully open and richly diverse landscape where everyone could thrive.

Those who colonized here from elsewhere in the world beginning in the 1600’s clearly did not share those same values, at least with respect to the land. They tended to view land and its many resources as property to be used as its owners saw fit. They worked hard to make the land productive, and we have all benefited in our current lifestyles from their centuries of labor.

However, by the mid-Twentieth Century, some visionaries began to see that there was something deeply wrong with this attitude about our relationship with the land. Aldo Leopold, in his Sand County Almanac, described the natural communities he loved beginning to disappear and laid out a set of values he called the “Land Ethic” as a way forward. John Curtis, in his Vegetation of Wisconsin, scientifically documented those communities down to their species composition, giving us important tools to identify and perhaps restore them. Rachel Carson, in her Silent Spring, made clear in a heart-rending way how our modern technologies could subtly but certainly destroy the animals and plants we most cherish.

Almost 50 years ago, inspired by those visionaries and others, a few small groups of young men and women began to seek out the last remnants of the prairies and oak savannas that had once dominated much of our upper Midwest landscape. Where they could, they began to cut away the encroaching brush and trees, plant rare seeds collected from other remnants, and, most importantly, rekindle the use of prescribed fire. No one paid them to do this – it was a labor of love to restore these tiny but exquisite islands of “biodiversity” (a term then recently coined).

Over time these local groups grew and had some success. Eventually, they came to understand it was not enough to just restore and manage these treasured remnants – they also had to be permanently protected and cared for by future generations. That required more financial, legal, and organizational resources than any one local group had. They also were learning fast, both from the infant science of restoration ecology and from their own hands-on experiences. They realized that by coming together regionally they could share both resources and knowledge to make what they were doing sustainable. However, they also knew that their dedicated communities of land stewards are intensely rooted in place. Thus, The Prairie Enthusiasts, with its structure of local volunteer chapters, was born.

Today that seed that was planted two generations ago has grown into an organization with 11 chapters in three states, almost 50 preserves protected through ownership or conservation easement, over $12 million in assets, and a volunteer membership of well over a thousand, served by a growing professional support staff. Many of our first generation of pioneering leaders have passed away or are retiring from the field, and even our second-generation leaders (myself included) are beginning to think about handing off the torch. Despite all this impressive history and growth, all of us in TPE believe that our work in the world is only just beginning and will become even more important as time goes on.

At this critical point in our history, as we consider once more how to sustain ourselves into the future, the Board of Directors, under the leadership of Executive Director Debra Behrens, undertook to develop a set of core values for TPE. The goal was to articulate what most essentially defines who we really are as an organization, what we cherish, how we behave, and how we make decisions together. Even though they have been mostly unstated, our core values have guided us on our journey so far. By making them clear to all, they can help inspire and guide those who will continue this journey after us.

As developed and approved by the Board, these are the core values of The Prairie Enthusiasts:

- Rooted in reverence for the Land

All that we are, and everything we do is deeply rooted in our love and respect for the Land – the communities of soils, water, plants, animals, and other living things of which we are a part. - Long view

The origins of the land are ancient. We are stewards of the present – the legacy entrusted to our care. Our actions shape what is possible for future generations. - Working together

We are responsible for caring for the land. Everyone has a unique ability to contribute. By working together, we form bonds that make our community stronger than ourselves. - Sharing knowledge

We honor wisdom and experience, science and the arts. We are seekers and teachers, sharing what we have learned and encouraging others to build on it.

I for one am very proud to be part of an organization based on these core values. Let me know what you think at sfulton@theprairieenthusiasts.org.

Keeping Prairies in the News

We are excited to share this Milwaukee Journal Sentinel article and the mention of The Prairie Enthusiasts below:

Wisconsin’s prairies shine in late summer, from Lapham Peak to the UW Arboretum

by Chelsey Lewis

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

August 19, 2021

As August winds down, the flowers in my home garden are nearing the end of their seasonal lifespan.

But here at Lapham Peak, yellow prairie dock and compass plant shoot into the sky, leaning toward the bright late-summer sun like miniature sunflowers. The goldenrod has just begun to bloom, its feathery yellow stalks peppering the hillsides. The wispy purple spikes of blazing stars are beginning to open, bees buzzing around them in search of pollen. A patch of black-eyed Susans are in full bloom, while a few yellow coneflowers hold on to their delicate yellow petals. Even the big bluestem grasses are getting in on the action, small buds emerging from the tips of their 6-foot-tall stalks.

I’ve missed the peak of wildflower season here, which usually comes in July, but late summer and fall are almost like a second spring for Wisconsin prairies, with a variety of colorful flowers blooming in August and head-high grasses reaching their apex before turning golden colors to complement the changing leaves.

This savanna might not have the flashy rock formations of Devil’s Lake, or the stunning sand dunes of Kohler-Andrae, but it’s one of my favorite places to hike in southern Wisconsin — not only because it’s not as popular as those places, but also because this landscape is so rare, and carries its own subtle beauty. I love that I can see the contours of the land, the big bluestem

grasses waving from the rolling hillsides in the late summer breeze. I love the little oak tree enclaves, like woodland oases in the middle of that sea of grasses. I love the almost comically tall prairie dock, its skinny stems trying to outreach those grasses in a quest for sunlight. The scattering of oaks here make this part of the park an oak savanna, a subset of prairies, which are landscapes populated by grasses, sedges (grass-like plants) and forbs (flowering plants). Prairies aren’t just pretty to look it and nice to walk through. They’re vital to species like American kestrels, bobolinks, sandhill cranes, eastern meadowlark, federally endangered Karner blue butterflies, bees and other pollinators.

They’re also vital to us. Prairie plants like big bluestem have deep root systems that filter groundwater and store carbon — the root systems are so extensive that they’ve been likened to underground forests. Prairies also create fertile soil for farming and grazing.

Prairies used to cover 2 million acres of Wisconsin, mostly in the southern part of the state. But as more settlers cleared the fertile land for farming, Wisconsin’s grasslands became a much rarer landscape. Today there are only about 12,000 acres left — less than .1% of the original landscape, according to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Conservationists are working to reverse that trend and restore prairies, but as with most things when it comes to the environment, it’s not easy. Land where prairies flourished, especially in the southeastern part of the state, is heavily populated, fragmented and farmed today.

Plus, prairies need something dangerous to thrive that other landscapes — including human populated ones — don’t like: fire.

Fire reduces the leaf litter that accumulates in grasslands, allowing sunlight to penetrate and warm the soil, which increases microbial activity that releases nutrients to feed new plants as they grow. Fire also helps eliminate non-native and faster-growing species like maple trees, which overshadow prairie plants and slow-growing oaks.

Before Europeans arrived, American Indian tribes actively burned prairies to improve grazing for game species, for safety (in order to see enemies as they approached), and to make travel easier.

In the Curtis Prairie at the UW Arboretum in Madison, it’s easy to see why they burned prairies to make travel easier.

Eight-foot-tall big bluestem tickled my arms and legs as I walked along a narrow path cut through the prairie. Without the trail, walking and navigating would have been a challenge.

I emerged from the tall grasses and walked into another segment of the prairie that had been burned more recently, as evidenced by the barely knee-high grasses. At least a portion of the prairie has been burned nearly every year since 1950, making it the

oldest ecologically restored prairie in the world. That restoration work began even earlier than 1950. When the Arboretum was dedicated in 1934, work was already going on to establish representations of all of Wisconsin’s plant communities, from the

northern forests to the southern plains. A portion of the land that used to be a farm was set aside to become prairie, and the first plants were planted in 1935.

“That had never been done before. Nobody really knew how to do it,” said Michael Hansen, land care manager for the Arboretum.

Since nobody had attempted that kind of land restoration before, nobody knew how to manage things like invasive grasses, left over from the fallow farm field that was there before. University of Wisconsin-Madison botany professor John Curtis came up with the idea

of intentionally burning the prairie to kill the invasive plants. Other universities out west were doing fire research at the time, but theirs was mainly geared toward increasing forage for livestock grazing, Hansen said. The idea of using fire to restore a landscape to prairie was new. In 1940, the first experimental burn was held at the Arboretum.

“They were assuming those native prairie plants were adaptive to fire and would respond really well, and that was what happened,” Hansen said.

The success of the first fire led to more experiments, and in 1950, the Arboretum began landscape-wide burns — establishing prescribed fire as an effective method to restore and maintain prairies.

Today, prescribed burns are used to manage grasslands throughout the Midwest. Trained professionals intentionally set the fires in defined areas under specific conditions to meet certain land management objectives. They’re typically set in the early spring or late summer or fall. communities. … I think that’s good just from a resilience standpoint and living on. The results are the big bluestem grasses and federally endangered rusty patch bumblebee that are found in the Arboretum and the soaring prairie dock and honking sandhill cranes in Lapham Peak. A snapshot of what Wisconsin was before Europeans moved in. A snapshot worth preserving.

“(Prairies) are part of our natural heritage, especially in this part of the country. They help make all that good soil that was farmed. It’s the foundation of that whole industry,” Hansen said. “It played an important part in the history of our state, and the Great Plains in general. … I think that’s important to try and preserve like you would an old historic building or some other artifacts.

“We often refer to different parts of the Arboretum as a living museum. It’s a collection of what our state used to look like in terms of the plant healthy land. But also for a healthy mind, I think diversity is important, too. Having that accessible to people is important.”

Prairies in southern Wisconsin

Here is a sampling of prairie sites you can visit in southern Wisconsin. Many prairies are protected as part of state natural areas. To find more, visit dnr.wi.gov/topic/Lands/naturalareas.

Havenwoods State Forest, Milwaukee: Don’t let the forest in this site’s name throw you — much of the interior of this urban forest is prairie and wetlands. Six miles of trails wind through those landscapes; the main loop is open to pets.

Lapham Peak, Delafield: More than 5 miles of trails wind through prairie and oak savanna on the west side of Highway C. Access the

trails from the Evergreen Parking lot (carefully cross Highway C) or a small Ice Age Trail parking lot on South Cushing Park Road. Leashed pets are permitted.

Ice Age Trail Stony Ridge Segment, Eagle: This 3-mile segment of the Ice Age Trail passes through a patch of prairie just west of the Kettle Moraine State Forest’s southern unit headquarters on Highway 59. Look for goldenrod and prairie dock in late August. Find parking and access at the Emma Carlin trailhead on County Highway Z or the forest headquarters.

Bald Bluff, Kettle Moraine State Forest-Southern Unit, Palmyra: American Indians

used this open prairie site on a bluff for signal fires and ceremonial dances, according to the DNR. U.S. troops also camped at the site during the Blackhawk War — future presidents Abraham Lincoln and Zachary Taylor among them. Today a half-mile nature trail climbs the bluff then connects with the Ice Age Trail and travels through a prairie that the DNR is working to restore. Find a parking lot on County Highway H south of Palmyra. Because this is a nature trail, pets are not permitted. Pets are permitted on the Ice Age Trail.

Riveredge Nature Center, Saukville: Ten miles of trails wind through a variety of landscapes, including a 28-acre prairie named for Lorrie Otto, who founded the natural landscaping movement and helped lead the push to ban DDT in Wisconsin and the rest of the

country. The nature center also has an all-terrain wheelchair that’s available to borrow for free through Access Ability Wisconsin. Trail fees are $5 for adults and $2 for kids ages 3-12 (free for kids 2 and under).

Pope Farm Conservancy, Verona: This former farm features a handful of restored prairies, including tall grass, short grass and oak savanna. The conservancy has a pamphlet on its website that outlines a one-hour self-guided walking tour of the prairies. The conservancy is open from sunrise to sunset daily and is free to visit. Dogs are not permitted.

UW Arboretum, Madison: More than 300 native grasses, sedges and wildflowers grow in the 73-acre Curtis Prairie, the world’s oldest ecologically restored prairie. The prairie’s 8-foot-tall big bluestem and Indian grasses are especially beautiful in the fall. A handful of trails wind through the prairie, which is accessible via a parking lot on McCaffrey Drive south of the visitor center. The Arboretum is home to a few other grasslands, including the 47-acre restored Greene Prairie, the 14-acre Wingra Oak Savanna, and the 53-acre Southwest Grady Oak Savanna.

Military Ridge Prairie Heritage Area, Dane and Iowa counties: About 30 miles west of the Arboretum are the Thomson Memorial Prairie and the Barneveld Prairie, part of the 95,000-acre Military Ridge Prairie Heritage Area. The area contains 60 prairie remnants in Dane and Iowa counties — one of the highest concentrations of native grasslands in the Midwest. The DNR has recognized the area as being a high priority for protection and management, and together with the Nature Conservancy — which manages the Thomson and Barneveld prairies — and other nonprofits and government agencies, is working to do that. The 706-acre Thomson Memorial Prairie does not have any official trails (and poison ivy is abundant, according to the Nature Conservancy), but the 1,193-acre Barneveld Prairie does have a rough, unmarked trail. The prairie is home to rare grassland bird species including bobolinks, meadowlarks, dickcissels and vesper sparrows — all species of special concern in Wisconsin; and upland sandpipers, a state threatened species. Dogs are permitted but must be on a leash from April 1 through July 31.

Pleasant Valley Conservancy, Black Earth: Nearly every landscape native to southern Wisconsin, including oak savanna and dry and wet prairie, is present at this 143-acre state natural area. Tom and Kathie Brock began restoration work on the property in 1995, and it continues today with the support of The Prairie Enthusiasts, a Viroqua-based nonprofit. More than 300 flowering species have been documented at the site, including rare ones like purple milkweed. Trails that wind through the property are open to hiking; bicycles and dogs are not permitted.

Contact Chelsey Lewis at clewis@journalsentinel.com. Follow her on Twitter

at @chelseylew and @TravelMJS and Facebook at Journal Sentinel Travel.