Who We AreSylvie Rising Operations Assistant...

Moths, Caterpillars, and Restoration of Remnants

Moths, Caterpillars, and Restoration of Remnants

By Robert J. Marquis

October 1, 2023

The goal of The Prairie Enthusiasts is to preserve and restore prairies and savannas in the Upper Midwest. By this we mean the protection of the entire ecosystem, not only the plants but also the animals and microbes and all their intricate interactions with those plants and each other. It has long been feared that conservation efforts might result in “empty forests” (or in our case, “empty prairies”) in which the landscape appears to be intact but close-up, many if not all the once known animal inhabitants are missing. A major challenge is to document the effects of prairie and savanna management on the animal participants and their place in prairie food webs.

The St. Croix Valley chapter in conjunction with Minnesota Department of Transportation (MNDOT) has managed a small remnant prairie (15 acres) for 18 years. This prairie, known as the Blueberry Hill Prairie, lies on the western bluff (Minnesota side) of the St. Croix River, just opposite Hudson, Wisconsin. Beginning in 2013, volunteers of the chapter began to convert 11 acres of adjacent agricultural land into prairie. In 2023, the chapter initiated efforts to document the interactions between insects and plants that occur in the Blueberry Hill Prairie.

Black light setup before sunset (left) and after in the dark (right). Photographs by R. Marquis

The Leadplant Flower Moth is endangered in Michigan (Michigan DNR 2023) and Indiana (Indiana DNR 2023), of special concern in Minnesota (Minnesota DNR 2023), and of greatest conservation need in Wisconsin (Wisconsin DNR 2023a). It is highly specialized in habitat, food plant, and phenology, and it is this combination of characteristics that makes it vulnerable. In the Upper Midwest, it is found only on prairie, caterpillars feed only on leadplant, and then only on the flowers and developing fruits of the plant. This lifestyle forces it into a very narrow time window of activity. In the Upper Midwest, we might suspect that caterpillars of this species could also survive and mature on fruits of Amorpha fruticosa (indigo bush), given that even highly specialized species often can feed on more than one member of the same plant genus. But there are no feeding records for A. fruticosa (Robinson et al. 2002), perhaps because that plant in Wisconsin and Minnesota grows in moist woodlands, along streams, and in floodplains. The moth does occur outside of the range of A. canescens, meaning that it must feed on additional host plant species.

Citations

Henderson, R. 2017. Of checks, balances & seed production. The Prairie Promoter 30:6,8.

Hess, M., and M.J. Hatfield. 2015. One plant at a time. The Prairie Promoter 28:1,4.

Indiana DNR. 2023. Indiana county endangered, threatened and rare species list. https://www.in.gov/dnr/nature-preserves/files/np-Indiana-County-Endangered-Threatened-Rare-Species-List.pdf. Accessed 30 August 2023.

Michigan DNR. 2023. Threatened and endangered species list. https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/managing-resources/wildlife/wildlife-permits/threatened-endangered-species/threatened-and-endangered-species-list. Accessed 30 August 2023.

Minnesota DNR. 2023. Minnesota’s endangered, threatened, and special concern species. https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/ets/index.html. Accessed 31 August 2023.

Robinson G.S., Ackery P.R., Kitching I.J., Beccaloni G.W., Hernández L.M. 2002.

Hostplants of the moth and butterfly caterpillars of America north of Mexico. Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute, v. 69, 824 p.

Summerville, K.S., Bonte, A.C. and Fox, L.C., 2007. Short‐term temporal effects on community structure of lepidoptera in restored and remnant tallgrass prairies. Restoration Ecology, 15(2), pp.179-188.

Swengel, A.B. and Swengel, S.R., 2006. Variation in detecting Schinia indiana and Schinia lucens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Wisconsin. The Great Lakes Entomologist, 39(3 & 4), p.6.

The Lepidopterists’ Society. 1983. Season summary. News Lepidoptera Society, no. 2.

The Lepidopterists’ Society. 1984. Season summary. News Lepidoptera Society, no. 2.

Wisconsin DNR. 2023a. Species of great conservation need. Wisconsin wildlife action plan. https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/WildlifeHabitat/actionPlanSGCN. Accessed 30 August 2023.

Wisconsin DNR. 2023b. Wisconsin’s endangered and threatened species list. https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/EndangeredResources/ETList . Accessed 30 August 2023.

Want to stay up-to-date on events like this happening in the St. Croix Region? Send us an email to make sure you’re on their chapter email list.

Change & Persistence Among Prairie Grasses

Change & Persistence Among Prairie Grasses

Story and Photos by Dan Carter

There are many misconceptions about prairies that cloud restoration, reconstruction, and management. Prominent among these is the tallgrass prairie “big four,” a concept that situates big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) atop the dominant hierarchy of plants on tallgrass prairie. The “big four” has far-reaching influence on grassland management, scientific study, and seed mix design. It’s Tallgrass prairie after all!

The “big four” are indeed co-dominant in many places where prairie vegetation occurs today. But, except for little bluestem, they were not historically the most dominant grasses on much of the prairie landscape, nor are they most dominant on many of the best remaining old-growth prairies.

John Curtis (1959)1 described the composition of the least disturbed old-growth prairies in Wisconsin. Big bluestem was present on all studied mesic prairies, but porcupine grass (Hesperostipa spartea), Leiberg’s panic grass (Dichanthelium leibergii), and prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis) were the most frequent grasses. Frequencies from Curtis are the percentage of square meter quadrats a species occurs within for a given community type — basically how likely the species is to be at your feet if you are walking in the prairie. porcupine grass was twice as frequent on mesic prairie as big bluestem! Big bluestem was the fifth most frequent grass on dry prairies behind little bluestem, side-oats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), long-stalked panic-grass (Dichanthelium perlongum), and prairie dropseed; and third most frequent on dry-mesic prairie behind little bluestem and side oats grama. Only on wet-mesic prairie was big bluestem the most frequent among the grasses. Still, on wet-mesic prairie little bluestem’s frequency was about three quarters that of big bluestem. Prairie cordgrass (Spartina pectinata) and Canada blue-joint grass (Calamagrostis canadensis) were the species most often present (frequency data lacking) on wet prairie.

In Iowa, The only grasses noted by Ada Hayden (1919)2 among the “principal” species of prairie remaining on the gently rolling uplands (mesic) immediately north of Ames, Iowa were porcupine grass and prairie dropseed. Later, Brotherson (1969)3, Kennedy (1969)4, and Glenn-Lewin (1976)5 studied composition on three old growth prairies in northern and western Iowa and found prairie dropseed, Leiberg’s panic grass, and porcupine grass to be the most common on uplands at the respective sites.

In the Red River Valley of NW Minnesota, Dziadyk and Clambey (1980)6 described old growth prairie communities dominated by blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis) and porcupine grass on dry ground, prairie dropseed followed by little bluestem on gentle slopes, little bluestem followed by prairie dropseed on moderately well-drained level areas, and big bluestem and slim-stem reed-grass (Calamagrostis stricta) together on low prairie over poorly drained soils.

Weaver’s and Clements’ (1938)7 concept of “true prairie,” which they extend to a region stretching from Illinois to Nebraska and northwest Minnesota to Oklahoma, is co-dominated by mid grasses—Porcupine grass, prairie dropseed, rough dropseed (Sporobolus compositus), little bluestem, side-oats grama, and needlegrass (Hesperostipa comata, in the west). Weaver worked extensively on prairies in the western part of the tallgrass prairie during the first half of the 20th century, including early study of fire effects at the Agricultural Experiment Station just north of Manhattan, Kansas. There, little bluestem and Junegrass (Koeleria macrantha) were initially the top two grasses (big bluestem was third). Composition shifted toward big bluestem with annual late spring burning but not late fall burning or earlier spring burning8,9. Indeed, late spring burning in the western and southwestern tallgrass prairie region to promote big bluestem for cattle pasture is part of why prairie composition changed there during the 20th century. Weaver and Clements observed these changes occurring and attributed them to the grazing and burning practices of the time, saying that the result was “that their [the mid grasses’] tallgrass competitors, notably Andropogon, gradually moved up the slopes and today appear to be essential members of the prairie relicts” (page 458).

Why did European land use sometimes drive compositional change towards the tall grasses like big bluestem?

Late spring burning favors the growth form of long rhizomatous, warm-season grasses. Their growing points remain below the soil surface until very late spring or early summer, so growth of their active shoots can continue uninterrupted despite damage to aboveground foliage with late spring burns. The growing points of most bunchgrasses (e.g., porcupine grass, prairie dropseed, Leiberg’s panic grass, little bluestem, Junegrass, etc.) rise above the soil surface and become vulnerable to fire shortly after they initiate growth. If these are burned off, the bunchgrasses must activate reserve buds to replace the lost shoots. That alone puts them at a disadvantage, but their reserves of buds tend to be small compared to long-rhizomatous big bluestem and Indiangrass10, so their regenerative capacity is sooner exhausted (meristem-limited) in response to removal of active shoots. The cool-season bunchgrasses are hit especially hard by late spring burning because of their early growth, but even little bluestem, a warm-season species, can be harmed by later spring burns due its difference in growth form. Prairie dropseed, another warm-season grass, is harmed because it initiates growth nearly as early as the cool-season species despite its warm-season physiology. On most upland old growth prairie, late spring burning favors a subset of native grasses that was not historically so abundant.

The effect of fire exclusion on composition can be similar to those of frequent late spring burning. Species with elongating rhizomes are better able to emerge through excessive accumulations of thatch. Hensel (1923)11 observed this 100 years ago in the Kansas Flint Hills. Little bluestem increased with annual early spring burning, but big bluestem replaced little bluestem atop the dominance hierarchy when fire was excluded. Weaver and Rowland (1952)12 also observed this in eastern Nebraska in the absence of burning, haying, or grazing:

“Consequences of the effects of the mulch upon the environment were production of a nearly pure, but somewhat thinner than normal, stand of Andropogon [big bluestem]. The understory of upland prairie had all but disappeared. The usual mid grasses of upland were few or none. Only a few taller forbs remained.”—Page 19

Burning in the presence of excessive litter accumulation, which often occurs on prairies that are occasionally burned (as opposed to frequentyly)kill or weaken little bluestem13 and other bunchgrasses (e.g., needlelegrass)14. Their buds are at or just above the soil surface and vulnerable to increased fire duration when excessive litter has built up. This is not the case for the deeply buried buds along the rhizomes of big bluestem or Indiangrass. Interestingly, excessive litter may interact with fire to affect prairie bunchgrasses and certain invertebrates (skippers: Hesperia ottoe and H. Dakotae)15 in similar ways, with responses contingent on the amount of litter accumulation!

Native bunchgrasses decrease for many of the same reasons in response to confined grazing. Porcupine grass is very palatable and emerges before most other prairie grasses, so it disappears quickly upon pasturage16. The long-rhizomatous prairie grasses also decrease in response to grazing16, but they persist and recover relatively well during rest periods because they have greater reserves of belowground buds available for recovery and their elongating rhizomes help them colonize openings where vegetation has been thinned by disturbance. The position of buds on these long-rhizomatous grasses an inch or two beneath the soil surface also protects their regenerative capacity from mechanical disturbance 10,17. Weaver recognized the importance of rhizomatous habit for recovery from disturbance, but not bud depth or number. Nonetheless, where grazing was too intense and prolonged, most prairie grasses were replaced by long-rhizomatous, cool-season species like Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), except on the driest sites1,2,16.

The work of Weaver, Curtis, Hayden, and others adds important context to our interpretation of more contemporary studies of prairie. They help us discern between research and management outcomes from altered grasslands that no longer retain old growth composition, and prairies that still do. Porcupine grass, little bluestem, prairie dropseed, side-oats grama, and/or Leiberg’s panic grass are usually among the prominent grass species on the best remaining old growth, upland prairies. All of those species differ from big bluestem in their ecologies in ways that have implications for management. Except side-oats grama, many of those differences stem from growth form, cool-season physiology, or both. Earlier work on composition also highlights the amazing persistence of well-stewarded and less historically exploited old-growth prairies in the face of unprecedented change. Upland old-growth prairies that retain much of their composition have typically experienced:

- fewer periods of excessive litter accumulation.

- fewer late spring burns and more burns between fall and early spring—the more frequent the better9,18,19. True prairie composition was and is an expression of dormant season fire.

- minimal fenced grazing. Free-roaming deer, elk, bison, and their predators/hunters are separate issues.

- less fragmentation19, but consider that small, less exploited prairies that are well-stewarded retain more of their historical botanical composition than landscape grasslands in the western tallgrass region. Little prairies are more vulnerable to neglect, which argues for their protection and care.

While the confluence of these conditions is tragically rare, the persistence of what remains is reason to keep hope. True prairie in the Midwest has been home to members of east-west and north-south expanding and contracting flora, fauna, and cultures for millennia. Even an island of old-growth prairie carries with it immeasurable ecological memory. We can kindle that and facilitate its recovery through stewardship and by building connections among prairie places and prairie people…especially if we can get our hands on more porcupine grass and Leiberg’s panic-grass!

References:

1 Curtis, J. 1959. The vegetation of Wisconsin University of Wisconsin Press. Madison, WI.

2 Hayden, A. 1919. Notes on the floristic features of a prairie province in central Iowa. Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science 25: 369-389.

3 Brotherson, J. 1969. Species composition, distribution, and phytosociology of Kalsow Prairie, a mesic tall-grass prairie in Iowa. Dissertation, Iowa State University.

4 Kennedy, R. 1969. An analysis of tall-grass prairie vegetation relative to slope position, Sheeder Prairie. M.S. Thesis, Iowa State University.

5 Glenn-Lewin, D. 1976. The vegetation of Stinson Prairie, Kossuth County, Iowa. Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science 83: 88-93.

6 Dziadyk, B. and G. Clambey. 1980. Floristic composition of western Minnesota tallgrass prairie. Proceedings of the Seventh North American Prairie Conference: 45-54.

7 Weaver, J., and F. Clements. 1938. Plant ecology. McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. New York and London.

8 Weaver, J., and A. Aldous. 1935. Role of fire in pasture management. Ecology 16:651–654.

9 Towne, G., and C. Owensby. 1984. Long-term effects of annual burning at different dates in ungrazed Kansas tallgrass prairie. Journal of Range Management 37: 392-397.

10 10 Ott, J., Klimešová, J., and D. Hartnett. 2019, The ecology and significance of below-ground bud banks in plants. Annals of Botany 123: 1099-1118.

11 Hensel, R. 1923. Recent studies of the effect of burning on grassland vegetation. Ecology 4: 183-188.

12 Weaver, J. and N. Rowland. Effects of excessive natural mulch on development, yield, and structure of native grassland. Botanical Gazette 114: 1-19.

13 Gagnon, P., K. Harms, K., Platt, W., Passmore, H., and J. Myers. 2012. Small-scale variation in fuel loads differently affects two co-dominant bunchgrasses in a species-rich pine savanna. PLoS ONE 7: e29674.

14 Haile, K. 2011. Fuel load and heat effects on northern mixed prairie and four prominent rangeland graminoids. Thesis, Montana State University-Bozeman.

15 Dana R. 1991. Conservation management of the prairie skippers Hesperia dacotae and Hesperia ottoe. Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 594, University of Minnesota.

16 Weaver, J. 1954. North American prairie. Johnsen Publishing Company. Lincoln, NE.

17 Klimešová J, and L. Klimeš. 2007. Bud banks and their role in vegetative regeneration – a literature review and proposal for simple classification and assessment. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 8: 115–129.

18 Bowles, M. and M. Jones. 2013 Repeated burning of eastern tallgrass prairie increases richness and diversity, stabilizing late successional vegetation. Ecological Applications 23: 464-478.

19 Alstad, A., Damschen, E., Givnish, T., Harrington, J., Leach, M. and D. Rogers. The pace of plant community change is accelerating in remnant prairies. Science Advances. 2: e1500975

Read more about Dan Carter’s work through our blog post: 2020 Landowner Services Update

Blue Sky Botany – Goldenrods

The baffling goldenrods swim in that giant taxonomic pool of asters, sunflowers, and thistles (Asteraceae). Their tiny, sun-emitting yellow-orange flowers are aggregated into marvelous “inflorescences” that appear to the uninitiated as single large blooms, whose growth forms are variously described as feather dusters, candles, or flattops. They are beloved by late summer insects, especially bees, and people with bee binoculars. Identification practice makes perfect.

There are too many for one article; I present a few that I have photos for.

(Photos and article by Rob Baller)

Early goldenrod (Solidago juncea)

Mid-August. Knee high on a tall person. Forming colonies whose flowering stalks are spaced closely enough to touch each other. Inflorescence a wide-open feather duster, spreading all directions, often slightly leaning and asymmetric. Stems and leaves totally smooth. Leaves tending to be similar size on the stem, but in fact reducing upwards. Mesic to dry prairie.

(Photo: Early goldenrod (Solidago juncea)

(Photo: Early goldenrod (Solidago juncea)

Missouri goldenrod (Solidago missouriensis)

Late August. Knee high. Forming colonies, whose blooming stalks are scattered too widely to touch each other, with many non-flowering stalks in between, giving the impression it’s just not a good year for blooming. Inflorescence a feather duster, typically but not guaranteed narrower than S. juncea. Stems and leaves totally smooth. Leaves largest at the base, clearly reducing upwards. Dry prairie, often sand.

(Photo: Missouri goldenrod (Solidago missouriensis))

(Photo: Missouri goldenrod (Solidago missouriensis))

Elm-leaved goldenrod (Solidago ulmifolia)

Late August. Waist-high. Inflorescence like a fireworks display, shooting slender wands of gold in several directions, often from upper leaf axils, the flowers born on the upper rim of the curve. Lower leaves broad and toothed like elm leaves. Mesic to dry, prefers light shade, oak savanna.

(Photo: Elm-leaved goldenrod (Solidago ulmifolia))

(Photo: Elm-leaved goldenrod (Solidago ulmifolia))

Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis)

Late August. Waist high or more. Forming colonies, sometimes covering fields. Inflorescence a flower duster whose overall outline is an asymmetric pyramid, leaning or arching to one side. Stems and leaves finely hairy, mostly toward the top of the plant. Mesic open sunny fields, prairie. Widespread volunteer; never planted on purpose.

(Photo: Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis))

Zigzag goldenrod (Solidago flexicaulis)

Late August. Waist high. Inflorescence presented in elegant marble-sized globs emerging from the upper-stem leaf axils, giving the stem and blooms a subtle zigzag appearance, which I find difficult to perceive. Lower leaves oval, toothed, with petioles tapering or ‘winged’ to the stalk. Mesic to dry, shady places, oak savanna.

(Photo: Zigzag goldenrod (Solidago flexicaulis))

Blue Sky Botany – Blazing Stars

Here are the four Liatris species most likely to be seen on our beloved Wisconsin prairie remnants. All are members of the sunflower family (Asteraceae). All have tiny pink to magenta flowers bundled into ‘floral cups’, with outer bracts on those cups that form layers like shingles, and positively identify the species. Good eyesight is helpful. All species bloom from the bottom upwards. They are discussed here in their order of seasonal blooming.

Dwarf blazing star (Liatris cylindracea)

Late July or early August. Shorter than knee high. Flower bundles loosely alternating up the stems, each bundle waving on a brief stalk more or less as long as the flower cup itself. Floral bracts are rounded like fingernails, with sharp points on each, adhering to the cup and never lifting away. Dry limey prairie.

Prairie blazing star (Liatris pycnostachya) aka ‘gayfeather’

Late July or early August. Knee to waist high. Flowers bundles spaced tightly on the stalk, the whole appearing like a rosy, feathery cattail. Floral bracts triangular, pointed, peeling away. Wet prairie, sometimes mixed into wetlands denoting where the ground is solid enough to stand on.

Rough blazing star (Liatris aspera)

Mid to late August, early September. Knee to waist high. No stalks connecting flower bundles to the main stem (sessile). Floral bracts distinctly rounded and cupping, creating a 3-D texture. Dry mesic to dry prairie, often in sand.

Showy blazing star (Liatris ligulistylis)

In my experience the least common of these. Mid to late August. Waist high. Very similar to L. aspera, except lower flower bundles are born on stalks about as long as the flowers. Mesic to dry prairie. Champion butterfly attractor.

Effect of Wild Parsnip Removal on Black Swallowtails

Very often in the world of prairie restoration, there are differences of opinion on the ‘best’ way to improve a piece of land. After receiving the question below, Dan Carter wrote a reply that we felt would be helpful to share with everyone.

QUESTION from a TPE member

Just wondering what protection measures you implement in removing wild parsnips to protect the black swallowtail butterfly caterpillar. Parsnips is one of their select host plant. I’ve been finding caterpillars on parsnips for years. I know it is a horrible plant, but we also need to be careful not to destroy a species.

ANSWER from Dan Carter

You raise the conundrum that is really at the center of everything that happens with land stewardship. Everything we do to the benefit of one species, community, or ecosystem has reciprocal consequences for others that must be weighed against one-another.

Chapters and members have a very broad range of goals and approaches for the properties they care for, so I don’t presume to speak for them—and I don’t know if anyone is doing anything specifically to protect black swallowtail caterpillars as they control invasive species, but I don’t think people generally are. The best I can do is give you my take.

Generally, there should be a plan and/or goals in place that any conservation action that takes place serves. In other words, it wouldn’t make sense to eradicate parsnip just for the sake of doing so. Where The Prairie Enthusiasts are concerned, eradicating parsnip most often serves two separate goals. One is to establish or restore the diverse native vegetation associated with now-imperiled natural community types that in turn supports a broader diversity other life forms (invertebrates, vertebrates, fungi)—particularly those dependent on vanishingly rare prairies, savannas, or other fire-dependent natural communities. Parsnip infestations impede doing so. The goal of establishing or restoring a diverse prairie calls for a different set of actions and priorities than the goal of promoting one or a few plant, insect, or other animal species.

The other goal is to raise awareness of prairies and their value among the public, and the particular hazard parsnip poses to people in the course of their interaction with nature can impede that goal. In my view the most compelling argument for prairie conservation is the beauty of its flora and fauna, because the people whose imaginations are captured by that beauty are among the prairie’s most loyal advocates.

In most instances, the flora being encouraged through the eradication of parsnip will be more diverse and support a broader diversity of insects and other wildlife, including black swallowtails, because members of the carrot family are part of the native prairie, savanna, oak woodland, and sedge meadow communities we are often working towards restoring or reconstructing. Black swallowtail as a species benefits from using a broad range of native and exotic carrot family plants across the landscape (gardens, old fields, degraded woodlands, and high quality remnant natural communities), so it is able to maintain populations on or readily recolonize areas where exotic carrot family plants like parsnip, poison hemlock, and wild chervil have been removed. For instance, I eliminated parsnip and Queen Anne’s lace from our property early on, but we still have a good population of black swallowtail, because we have seven other native members of the carrot family native to prairies and savannas. Black swallowtail remained present on the surrounding landscape where its weedy or invasive host plants were still present and was able to recolonize—but now we now have a lot of other plant and insect species that we did not have before…and our children can romp around in it without fear of severe blisters. Native species I’ve observed black swallowtail larvae on include (but aren’t limited to) golden Alexanders, smooth meadow parsnip (Thaspium trifoliatum), yellow pimpernel, honewort, anise-root, sweet cicely, common water-hemlock, angelica, and black snakeroot (several species).

It would probably be possible to move caterpillars off of parsnip to other host plants, but oftentimes caterpillars won’t do as well if they are moved between species during their development. Doing this would also likely not be practical for larger infestations. …but in the case of black swallowtail, the local population will be fine so long as other host plants remain present, because just about all of the landscape outside of mowed lawn, paved areas, and cultivated fields still supports host plants, and black swallowtails disperse well, so the sites we might manage by eliminating parsnip generally already support other host plants, or they will.

I realize this may not get to the heart of your concern about the caterpillars on the parsnip, but concerns like yours either are or should be taken to account in the work that we do alongside all of the other factors that must be weighed in the course of good land stewardship.

Dan Carter, PhD

Landowner Services Coordinator

The Prairie Enthusiasts

Blue Sky Botany – June

Botanist and early TPE member Rob Baller created this series for our friends at Blue Mounds Area Project. The “blue sky” technique is Rob’s favorite for taking stunning plant photographs. Let him know what you think at robertballer@outlook.com.

ALWAYS get permission from the property owner if you want to try this technique.

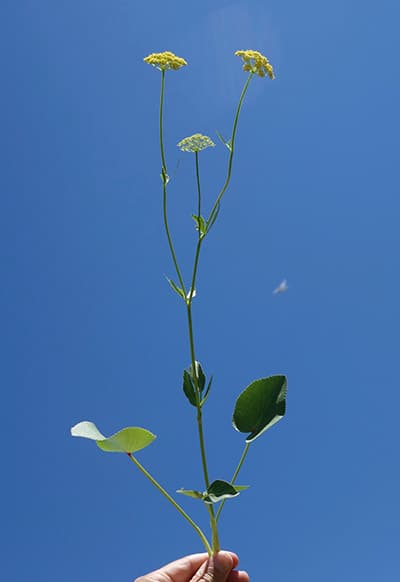

Yellow umbels (Zizia spp., Taenidia integerrima, Pastinaca sativa)

These four yellow umbel (flowers arranged on branches like umbrella spines) plants bloom in June with their lofted blooms and deeply cut or divided leaves showing their relation to carrots and parsley. All grow in full sun to open oak woods, dry to moist.

Common golden-Alexander (Zizia aurea): Knee-high. Leaves divided nearly all the way to their junction into 3-5 leaflets. Leaf margins always toothed. Moist to dry soil, usually full sun. Early June.

Zizia aurea. Photo by Rob Baller

Zizia aurea. Photo by Rob Baller

Heart-leaved golden-Alexander (Zizia aptera): Knee-high. Leaves on stem resemble those of the common Alexanders, but leaves at the base are distinctly heart-shaped, finely toothed and often bordered with an intense dark red (but not always). Tends to grow in medium to dry soil, bright sun. Early June.

Zizia aptera. Photo by Rob Baller

Yellow pimpernel (Taenidia integerrima): Knee- to waist-high. Tender leaves divided into 3-5 leaflets, usually with no teeth on margins. Flowers borne on long, well-spaced wires, giving a loose and almost spherical look. Prefers oak savanna, partial shade, and dry to medium soil. Early June.

Yellow pimpernel. Photo by Rob Baller

Wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa): Invasive. Waist- to head- high. Stems with vertically running ridges. Lower foliage a ladder-like arrangement of 5-9 separate leaflets; upper leaflets in groups of 3-5. Always toothed. Umbels form a more flat-topped appearance than any of the preceding species. Full sun, moist to dry. A close relative of the domestic garden parsnip, this non-native pest contains clear sap that causes blisters on the skin about 2 days after contact. The quest to control this plant inspired the creation of the Parsnip Predator, offered for sale by TPE.

Look out! Photo by Rob Baller

Angelica (Angelica atropurpurea) and cow-parsnip (Heracleum maximum)

Two towering relatives in the carrot family. Both reside in damp, springy places and become man-high with baseball-sized clusters of flowers presented in umbels. Both bloom in early June.

Angelica (Angelica atropurpurea): Tends to be the first to bloom. Taller than Rob. Flowers are grouped into spheres, whose sub-groupings of tiny flowers form yet smaller spheres. Flowers greenish-white to purple. Stems dark purple and smooth. Prefers squishy wetlands; if you’re next to it, you’re in water up to your ankles. Full sun.

Angelica. Photo by Rob Baller

Cow-parsnip (Heracleum maximum, formerly H. lanatum): Taller than Rob. Flowers form an arched to nearly flat-topped umbel, always milky-white, the whole of it having a woolly appearance (giving its former name, “lanate”). Stems with soft, close hairs. Prefers rich, damp ground, usually not so squishy and often in areas of partial shade, like mesic oak savanna.

Cow-parsnip (moo). Photo by Rob Baller

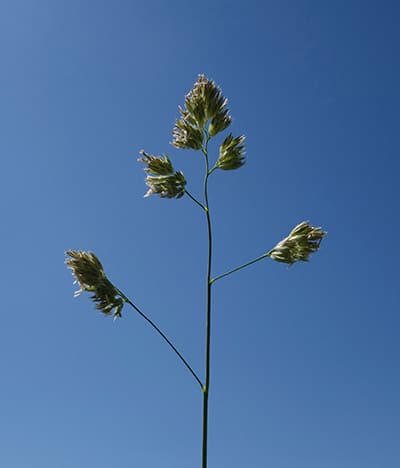

Orchard grass (Dactylis glomerata) and reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea)

Two non-native grasses, abundant on roadsides and in grassy fields. Farmers plant them; restorationists try to control them because they are non-native and aggressive. Naturalists frequently rush to the ligule (a small, translucent membrane where the leaf separates from the stem) for identification, but these are often torn and distorted. I turn to the infinitely easier flowering architecture.

The flowering structures of both species are borne on slender wires at the top of the grass. The outlines they form can be distinguished at a distance. The only difficulty is that while reed canary spreads its flowering heads open widely during flowering, the heads may contract a week later, altering their appearance.

Orchard grass (Dactylis glomerata): First of the two grasses to rise in the field, and to flower, usually in late May. Knee- to waist-high. When in flower, the grass typically has just one outward-branching “limb” followed by a distinct space, then a few other “branches” with flowers. An outline drawn around all of the flowering structures at top of the stem would be almost as wide as it is tall.

Orchard grass is planted for forage and hay. It grows best on mesic soils. Often found persisting in fields planted to prairie, it is of low concern because fire and competition will lessen it over time.

Orchard grass. Photo by Rob Baller

Reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea): Second to rise and bloom, usually about a week after orchard grass (early June). Waist- to head-high, but reclining later in the summer. The flowering heads have many (8-14) branching wires more or less of similar length, appearing to form a ladder that gradually closes to a point as you follow it upward. An outline drawn around all of the flowers looks like a spearhead. The heads are widest during blooming, after which they contract to a tapered spear outline for the rest of the season.

Reed canary is routinely planted agriculturally on any damp soil. Spreads aggressively, voluntarily, anywhere silt is deposited, especially along stream banks and in any formerly tilled, sunny, floodplain. Reed canary is a high concern to restorationists and is hard to eradicate.

Reed canary grass. Photo by Rob Baller