Who We AreSylvie Rising Operations Assistant...

Stability Part One: Why I Recommend Frequent Dormant Season Burning

Stability Part One: Why I Recommend Frequent Dormant Season Burning

Photos and Written by Dan Carter

Prairie and Oak Ecosystems Depend on Stability

A central organizing concept of my ecological education was that prairie and oak ecosystems are “disturbance dependent.” This view emphasizes that we stop these ecosystems from becoming something else and deemphasizes that they are something in and of themselves—old growth. Disturbance-centric thinking remains prominent in prairie and oak ecosystem science and management. For example, under the heading “Managing Prairies” the Minnesota DNR website[1] states:

“Prairie is a ‘disturbance-driven’ ecosystem: plants and animals have adapted to withstand and even thrive with regular disturbance—fire, grazing, and periodic droughts. Each disturbance favors different plants and animals, so it is important to include a variety of disturbance types, timing, and frequency.”

The advice to mix things up sounds reasonable, disturbances do favor different plants and animals, and certain events or conditions must occur to prevent oak and prairie ecosystems from becoming something else.

The problem is that disturbance[2] can simplify ecosystems and promote species that are not conservation priorities at the expense of the old growth that we would like to conserve or emulate. Given what we know about historical structure, composition, and the individual ecologies of the species that comprise old-growth prairie and oak ecosystems, I believe that the prevailing view about how these ecosystems sustain themselves—disturbance—is wrong. Instead, stability should be a central organizing idea guiding our stewardship.

Centering management around a core principle of stability does not mean doing less. Indigenous Peoples’ use of dormant season fire and its interaction with landscape, climate, and biota was the lattice over which our prairie and oak ecosystems came together over thousands of years. Managing for stability means keeping this in mind and building an understanding of how it governs ecological processes. In this article I will discuss prescribed fire, and how it can function as a stabilizer or a destructive disturbance depending on how we use it. I intend to discuss other management practices in turn.

A fire-starved remnant prairie that persisted long enough to be protected because haying prevented build-up of smothering thatch and removed nutrients.

A close-up showing the deep accumulation of thatch in the fire-starved remnant prairie. It would be difficult to burn at this point without producing high fire intensity, particularly long duration of burning near the soil surface.

Excessive leaf litter accumulation in an oak woodland.

Both high intensity and growing season fires have destabilized this former savanna.

Frequent Dormant Season Fire is Stabilizing; Infrequent, Intense, and Growing Season Fire is Destabilizing

First, recognize that critical areas of fire ecology in Midwestern prairie and oak ecosystems are forgotten, understudied or not studied through the posing of questions and collection of data that informs our mission. Synthesis of what we do know is also in short supply. What follows is my earnest attempt using applicable science, cases of success and failure, and historical information to explain why I often advocate for very frequent[3] dormant season burning. This topic is also difficult to flatten into a linear narrative, such are the ecological relationships. Many threads could be drawn from this that merit their own separate discussions.

I don’t refer to prescribed fire as a tool. A Pulaski is a tool. Fire is an integral part of Upper Midwestern prairie and oak ecosystems. Fire is their primary stabilizing agent and was probably the greatest single consumer of their plant production in the past (Wendt et al. 2023[4]). The more frequently contemporary Midwestern prairie and oak ecosystems burn in the dormant season, the more they retain historical or old-growth composition over time (Towne and Owensby 1984[5], seasonality of fire; Milbauer and Leach 2007[6], Bowles and Jones 2013[7] and Alstad et al. 2016[8], frequency of burns mostly in early spring or fall). See my article in the 2023 fall issue of The Prairie Promoter[9] for a discussion specifically about how fire exclusion and altered fire seasonality have affected prairie grass species composition. With enough dormant season fire and other appropriate management, incredibly diverse and complex examples of prairie and oak ecosystems have recovered and persist. Black Earth-Rettenmund Prairie and Sugar River Savanna are excellent examples. Unfortunately, few places are managed this way. We need more demonstrative examples for science and inspiration[10]. Sites burned too infrequently lose old-growth-associated composition and structure—conservative[11] plant species and the fauna they support, so do sites that receive too many growing season fires. Hopefully, what follows provides insights into how lack of fire and growing season fire can be destabilizing.

Most historical accounts describe ignitions preceding Indigenous Peoples’ displacement as anthropogenic, autumnal[12], and frequent over large areas (Stewart 2002[13]; Wilhelm and Rericha 2007[14], 2012[15]; McLain et al. 2021[16]). Wilhelm and Rericha refer to this as the “ancient, culturally mediated rhythm,” and it prevented smothering thatch and litter accumulation, reduced fire intensity (especially duration), and minimized growing season nutrient availability. Fire in the dormant season is not unlike frost to prairie or oak ecosystems, something that in its proper season falls within the parameters that governed their original formation and the subsequent evolution. Fidelity to that seasonal rhythm is not anachronistic; it is important for the restoration and maintenance of prairie and oak ecosystems. It has served us well as the climate has changed dramatically over the last several decades, and it will probably continue to do so if we allow it.

There is disagreement between historical accounts and scientific estimates of fire frequency based on fire scars (e.g., Allen et al. 2011[17]), which typically estimate fire-return intervals of several years to a decade. The fire regimes that best-maintain prairie and oak ecosystems on the contemporary landscape lend strong support to the historical accounts. Fire scar studies capture fire events sufficiently intense to scar oaks on landscape positions where trees historically occurred—not prairies. Very frequent or annual fires in oak woodlands have low intensity due to reduced fuel loads and may fail to scar oak trees and subsequently be detected in the fire scar record (McEwan et al. 2006[18], Knapp et al. 2017[19]). Climate change and other anthropogenic changes at scales ranging from local to global may also necessitate that we burn differently, regardless of historical frequency. We should strive to do what works, regardless which estimates of historical frequency are right.

The benign removal of litter and thatch that would otherwise smother and weaken the sod of native graminoids and forbs typical of prairies and oak ecosystems is among the most important stabilizing roles of fire. When prairie fire is too infrequent, thatch accumulation thins the herbaceous vegetation and “prairie understory” species fade while composition shifts in favor of taller species and those with longer-elongating rhizomes that can grow up through the debris (e.g., Weaver 1952[20]). A similar phenomenon occurs in remnant oak woodlands, which support continuous grassy / sedgy, often forb-rich herbaceous vegetation. Without removal of oak leaf litter by fire or another agent like wind (as on convex topography and windswept slopes), many woodland herbaceous species are smothered. Midland shooting star (Primula meadia) is an example from both prairies and woodlands that is diminished in this way. When searching for remnant woodland vegetation at long fire-starved sites, I’ve learned to seek topography that is subject to removal of fallen leaf litter by wind. Perhaps because this is such a plain mechanism, direct smothering effects of leaf litter are under-researched in woodland ecosystems (but see Sydes and Grime 1981[21], Vander Yacht et al. 2020[22]). Once the herbaceous sod in a prairie, savanna, or woodland is thinned and degraded, it becomes more vulnerable to invasion and woody encroachment.

Thatch and leaf litter don’t only smother. Increased fuel loads lead to greater fire intensity as fire burns down through accumulated debris. This can injure herbaceous species whose regenerating buds are held at or above the soil surface, species like little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) and prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis) and cause greater harm to certain invertebrates overwintering at or just below the soil surface (e.g., Dana 1991[23]). Intense fire can injure mature, healthy oak trees and lead to abrupt changes in canopy closure. In relatively nutrient poor oak and pine ecosystems, long periods without fire can lead to duff development (an organic layer below the leaf litter), and when trees proliferate roots in the duff, fire can subsequently consume those roots with lethal results (Carpenter et al. 2021[24]).

Frequent prairie fires can reduce nitrogen availability (e.g., Ojima et al. 1993[25]) through volitilization, and the same may be true in woodlands where fire is frequent and consumes primarily fine fuels. Frequent fire may also contribute higher carbon to nitrogen ratios in oak litter, which can then immobilize more nitrogen and reduce nitrogen availability (Hernández and Hobbie 2008[26]), but it does not necessarily lead to nutrient losses from the ecosystem (Sharenbroch 2010[27]). Conversely, adding nitrogen destabilizes prairie composition (Koerner et al. 2016[28]). Old-growth vegetation in fire-dependent ecosystems is comprised largely of species that rely more on year-to-year survival versus annual reproductive output or seed banks for population persistence. Old-growth vegetation also tends to be nutrient efficient and produce slower-decomposing, flammable litter. Dormant season fire sustains that vegetation by removing accumulated detritus without significant injury to established herbaceous plants. Conversely, the strategy of most weedy species is to persist in the seed bank or disperse widely and respond to available nutrients and light by growing and reproducing rapidly. The litter they produce tends to be less flammable and decompose rapidly, which promotes faster nutrient cycling and greater nutrient availability. Growing season fires cook the aboveground living tissues of conservative herbaceous plants. In addition to that direct harm, which can be substantial and lead to compositional changesrelated to plant growth form and regeneration strategy, it results in the hard-won nutrients present in their tissues and light intercepted by their foliage being made available. This creates an environment where soil warmth, light, and nutrient cues align to encourage the establishment of opportunistic, weedy species. Nitrogen (nitrate), for example, serves as a germination cue for raspberries (e.g., Jobidon 1993[29]) and a variety of herbaceous weeds, particularly in combination with light (Soltani et al. 2022[30]). Heat from fire also has more opportunity to penetrate the soil during the growing season, because the latent heat of water buffers soil temperature, and near-surface soil moisture content usually decreases as the growing season proceeds. Exposure to heat can break seed dormancy in smooth sumac (Li et al. 1999[31]), which I think is worth considering! Where late spring or summer burning has occurred and sumac is on the landscape, look for sumac seedlings. Setting the flora aside, greater direct negative impacts of growing season burning on certain fauna are well known (e.g., Harris et al. 2020[32]); these magnify tensions between the use of prescribed fire and rare animal species. Dormant season burning minimizes them.

Conservation-oriented land managers often burn during the growing season to maximize injury to unwanted woody vegetation. The evidence that this makes a meaningful difference is scant. Meunier et al. (2021)[33] showed decreases in resprouts per individual (not mortality) for northern pin oak (Quercus ellipsoidalis) and bush honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.) with August burning relative to April or June burning, but they found no similar benefit for common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica). Hartnett and Wilson (2011)[34] found that spring and summer growing season burns led to increases in smooth sumac relative to fall and winter burns.

Another argument for burning during the growing season is that it can be associated with increased herbaceous plant richness and primary productivity[35]. These may be go-to response variables for research ecologists and agronomists, but they tell us little about ecological integrity[36] and can indicate ecosystem degradation. As fire-dependent ecosystems degrade their richness is a function of extirpation of the species that were originally present and colonization by opportunistic species or those associated with other ecosystem types[7,8]. For example, widely dispersed woodland species like stickseed (Hackelia virginiana) can accompany woody encroachment into the prairie. Inventories of degrading sites are often packed with such species—even while the original species are hanging on by a thread. Likewise, primary productivity can increase with ecosystem degradation—even when an ecosystem undergoes profound change that impairs other ecosystem functions and resilience (De Leo and Levin 1997)[37]. Imagine a sedge meadow that transitions to Phragmites dominance. Productivity is used as a measure of ecosystem efficiency, but the sun’s energy does not just go into biomass production; it also fuels production secondary metabolites, which are the basis for countless specialized interactions between plants, fungi, bacteria, and both invertebrate and vertebrate fauna! High quality prairie and oak ecosystem herbaceous sods are often low in stature, but that does not mean that they are thermodynamically inefficient. They are just doing different things—more interesting things if you ask me! Increased productivity aboveground may be indicative of nutrient availability destabilizing composition by causing a shift from belowground competition to aboveground competition for light (e.g., Wilson and Tilman 1993[38]; Goldberg et al. 2017[39]), which favors species with opportunistic strategies.

Frequent dormant season burning can keep most woody encroachment at bay when the sod is strong, and frequent dormant season burning results in a strong sod. When they occur together, dormant season fire and high integrity herbaceous sods are stable and autocatalytic. For example, quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) has remained a minor presence at Sugar River Savanna for fifty years with near-annual burning[40]. Aspen would most likely overwhelm a similar site in the absence of frequent fire, but the herbaceous sod there is tightly interwoven. The same is true for sumac in more degraded Flint Hills prairie in Kansas[33]. Upon cessation of frequent fire, species like aspen, smooth sumac, and gray dogwood (Cornus racemosa) quickly take over, if they have a toehold, and the ecosystem changes states. This isn’t because fire is ineffective. It’s because very frequent dormant season fire is a defining part of the autocatalytic system, and it is underutilized.

Sugar River Savanna has been managed with near-annual early spring (dormant) fire for fifty years.

Frequent dormant season burns stabilize prairie and oak ecosystem composition, structure, and ecological processes by removing smothering debris and minimizing growing season nutrient availability without injury to conservative, old growth vegetation. Are there situations where less frequent fires, or disturbance-inducing intense or growing season fires are appropriate? I can think of examples related to specific management needs or goals. Many are applicable to degraded sites where conservation of one or a few species or the need to generate income outweigh other considerations in the short term. Those instances have merit, but such decisions should be based on an understanding of the relevant ecological processes and both direct and indirect effects. Historically, disturbance fires did occur. Some fire scars were laid down during the growing season. Lightning can ignite summer fires in drought years. Those fires may have had important effects on ecosystem structure, composition, and processes in the past, but the fire-dependent ecosystems of the past were also buffered by intact ecological landscapes free of invasive species. Remaining prairie and oak ecosystems can no longer rely on landscape ecological processes for resilience. This should give us pause when we consider deviating from the “ancient, culturally mediated rhythm” to mix things up, hit woody vegetation hard, or simply get more fire on the ground.

References

[1] Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Website (accessed 1/12/24): https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/prairie/manage/managing-prairie.html

[2] For the sake of this discussion, disturbance is an event that causes mortality, injury or stress to an ecosystem or one of its components that causes deviation from a reference state.

[3] How frequent is frequent? It depends on the ecosystem type. Relatively productive mesic prairies may need to be burned more often than every other year maintain structure, composition, and ecological processes. Some dry, sandy sites require multiple seasons to build up enough fuel to burn.

[4] Wendt, J., et al. (2023) Past and present biomass consumption by herbivores and fire across productivity gradients in North America. Environmental Research Letters 18.12: 124038.

[5] Towne, G., & Owensby, C. (1984). Long-term effects of annual burning at different dates in ungrazed Kansas tallgrass prairie. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 37(5), 392-397.

[6] Milbauer, M. L., & Leach, M. K. (2007). Influence of species pool, fire history, and woody canopy on plant species density and composition in tallgrass prairie1. The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society, 134(1), 53-62.

[7] Bowles, M.L., & Jones, M.D. (2013). Repeated burning of eastern tallgrass prairie increases richness and diversity, stabilizing late successional vegetation. Ecological Applications, 23(2), 464-478.

[8] Alstad, A.O. et al. (2016). The pace of plant community change is accelerating in remnant prairies. Science Advances, 2(2), e1500975.

[9] Carter, D. (2023). Change and persistence among prairie grasses. Prairie Promoter, Summer, 10-12.

[10] Very few sites in most research cited are burned very frequently, for example in Milbauer and Leach (2007), burn frequency was divided into three classes, the most frequent class including sites that had been burned between four and seventeen times in twenty years. We need more sites that are burned more often than every other year, including annually for greater resolution of fire’s effects.

[11] Conservative plant species are those that are relatively intolerant of degradation. Species are assigned coefficients ranging from zero to ten; those with higher coefficients are more indicative of a relatively stable and undisturbed conditions where they occur. The three most frequent grasses on WI mesic prairie, for example, all have coefficients of nine or ten. About 80 percent of Wisconsin’s native flora have C-values of four or greater.

[12] A bias based on more travel in fall or early winter versus when conditions were muddy in early spring has been raised, but if that were the case, fires were overwhelmingly at the edge of or within the dormant season, and there is as of present no evidence beyond conjecture to suggest early spring fires were as or more common or extensive than autumnal fires. We need more science to elucidate ecological differences, but practically it may be advantageous to utilize fall burning opportunities to guard against the possibility of rapid spring green-up, as happened in 2023.

[13] Stewart, O.C. (2002). Forgotten fires: Native Americans and the transient wilderness. University of Oklahoma Press.

[14] Wilhelm, G., & Rericha, L. (2007). Timberhill savanna assessment of landscape management. Conservation Research Institute, Elmhurst, IL.

[15] Wilhelm, G. & Rericha, L. (2012). Inventory and Assessment Plan for Stewardship and Monitoring at Hitchcock Nature Center. Conservation Research Institute, Elmhurst, IL.

[16] McClain, W. et al. (2021). Patterns of anthropogenic fire within the midwestern tallgrass prairie 1673–1905: Evidence from written accounts. Natural Areas Journal, 41(4), 283-300.

[17] Allen, M. S., & Palmer, M. W. (2011). Fire history of a prairie/forest boundary: more than 250 years of frequent fire in a North American tallgrass prairie. Journal of Vegetation Science, 22(3), 436-444.

[18] McEwan, R. W., et al. (2007). An experimental evaluation of fire history reconstruction using dendrochronology in white oak (Quercus alba). Canadian Journal of Forest Research 37(4), 806-816.

[19] Knapp, B. O., Marschall, J. M., & Stambaugh, M. C. (2017). Effects of long-term prescribed burning on timber value in hardwood forests of the Missouri Ozarks. In Proceedings of the 20th Central Hardwood Forest Conference (pp. 304-313). USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. GTR-NRS-P-167, Northern Research Station, Newtown Square, PA.

[20] Weaver, J. & Rowland, N. (1952). Effects of excessive natural mulch on development, yield, and structure of native grassland. Botanical Gazette 114: 1-19.

[21] Sydes, C., & Grime, J.P. (1981). Effects of tree leaf litter on herbaceous vegetation in deciduous woodland: I. Field investigations. The journal of ecology, 237-248.

[22] Vander Yacht, A.L. et al. (2020). Litter to glitter: promoting herbaceous groundcover and diversity in mid-southern USA oak forests using canopy disturbance and fire. Fire Ecology, 16(1), 1-19.

[23] Dana R., (1991) Conservation management of the prairie skippers Hesperia dacotae and Hesperia ottoe. Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 594, University of Minnesota

[24] Carpenter, D.O. et al. (2021). Benefit or liability? The ectomycorrhizal association may undermine tree adaptations to fire after long-term fire exclusion. Ecosystems, 24, 1059-1074.

[25] Ojima, D.S. et al. (1994). Long-term and short-term effects of fire on nitrogen cycling in tallgrass prairie. Biogeochemistry 24:67–84.

[26] Hernández, D.L., & Hobbie, S.E. (2008). Effects of fire frequency on oak litter decomposition and nitrogen dynamics. Oecologia, 158: 535-543.

[27] Sharenbroch, B.C. (2010). Ecological impacts of long-term, low intensity prescribed fire in Midwestern oak forest. Report to: The Illinois Department of Natural Resources: 1-102.

[28] Koerner, S.E. et al. (2016). Nutrient additions cause divergence of tallgrass prairie plant communities resulting in loss of ecosystem stability. Journal of Ecology, 104(5), 1478-1487.

[29] Jobidon, R. (1993). Nitrate fertilization stimulates emergence of red raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) under forest canopy. Fertilizer research, 36, 91-94.

[30] Soltani, E. et al. (2022). An overview of environmental cues that affect germination of nondormant seeds. Seeds, 1(2), 146-151.

[31] Li, X. et al. (1999). Anatomy of two mechanisms of breaking physical dormancy by experimental treatments in seeds of two North American Rhus species (Anacardiaceae). American Journal of Botany, 86(11), 1505-1511.

[32] Harris, K.A., et al. (2020). Direct and indirect effects of fire on eastern box turtles. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 84(7), 1384-1395.

[33] Meunier, J., et al. (2021). Effects of fire seasonality and intensity on resprouting woody plants in prairie‐forest communities. Restoration Ecology, 29(8), e13451.

[34] Hajny, K.M., et al. (2011). Rhus glabra response to season and intensity of fire in tallgrass prairie. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 20(5), 709-720.

[35] The biomass produced by primary producers (e.g., plants).

[36] An ecosystem with ecological integrity is comprised of the full range of parts and processes expected for a region and has its evolutionary legacy intact.

[37] De Leo, G.A., & Levin, S. (1997). The multifaceted aspects of ecosystem integrity. Conservation ecology, 1(1).

[38] Wilson, S.D., & Tilman, D. (1993). Plant competition and resource availability in response to disturbance and fertilization. Ecology, 74(2), 599-611.

[39] Goldberg, D.E., et al. (2017). Plant size and competitive dynamics along nutrient gradients. The American Naturalist, 190(2), 229-243.

[40] Henderson, R. (2022). Effect of long-term annual fire on tree establishment and growth in an oak savanna (Poster). The Prairie Enthusiasts Annual Conference: Inspired by Resilience.

Paying Attention to the Season During Restoration Work

Paying Attention to the Season During Restoration Work

By Jim Rogala

October 3, 2023

Prairie restoration land managers, whether landowners or those working on public or protected lands, typically have long lists of management needs. I’m no exception. My list contains many lifetimes of work I could do, so I prioritize tasks and tackle urgent needs first. These are typically long-range plans that span years and even decades. However, there is another component to selecting which task to work on at a shorter time scale: seasons of the year.

I’ve always had this seasonal aspect of restoration in my mind, but that is not very conducive to sharing it with others. As a past member of The Prairie Enthusiasts Education Committee, I proposed doing a simple guide to formalize the seasonal aspect of prairie restoration.

There are many factors that contribute to selecting which time of the year someone might do a specific task. Some examples are:

Plant Physiology

The translocation of materials in plants can vary drastically by season, not only in the rate of movement but also the dominance of some movement over others across seasons. Also, there are times when most of the energy in a plant is above ground, and other times it is below ground.

Herbicide Efficacy

Herbicides have temperature ranges that are best suited for their effectiveness.

Preparation for Upcoming Tasks

Some tasks are simply preparing for other tasks. If the work is not done to meet the requirements of performing an upcoming task, then you may have to delay doing something for a year.

Snow Cover

The presence of snow is a good time for some tasks and not good for others.

Keeping such factors as these in mind, it becomes obvious that performing some restoration work is best done in a particular season. Some examples are:

-

-

-

- When cutting and treating trees and brush, consider the optimum season to best translocate the herbicide to the location of action. If it is too cold or too hot, and the translocation is slow. Oil-based herbicides also volatilize at high temperatures.

- For non-herbicide methods such as repeated cutting, summer is the preferred time because most of the energy stores are above ground. For clonal species, it is critical to not cut in fall or winter if you are not applying herbicide, as this will promote resprouting from nodes.

- Mowing firebreaks in preparation for a spring burn should be done before winter to minimize dry debris on the break.

- Brush pile burning is best done in the winter when there is snow on the ground.

-

-

The work of the Education Committee, with helpful reviews from our Science Advisory Group, yielded a document titled: Quick guide to restoration practices: Timeframes and general methods. We hope those that are doing restoration find the guide informative and useful in planning seasonal activities. And, as you might notice, there are no seasons with nothing to do!

Quick Guide to Restoration Practices: Timesframes and General Methods

Guide to Restoration Practices

Timeframes and General Methods

Story by Jim Rogala

October 3, 2023

The timing of most mechanical and chemical treatments to control unwanted plants is most effectively performed when taking into consideration plant anatomy and physiology, phenology, and the physical conditions of the site. For example, knowing where the cells that translocate materials are located (i.e., anatomy), along with how and when this translocation is occurring (i.e., physiology) are critical. For herbicide treatments, translocation from the point of application to area of action needs to be considered. Many mechanical treatments focus on depleting energy stores and therefore timing to disrupt the translocation is key. There are also weather conditions within seasons to consider, such as rain forecasts prior to herbicide application or hot conditions that slow the translocation process.

Below are some recommendations for seasonal, priority management actions. This information is intended to serve as a starting point for planning the timing of work to have maximum desired impact and not to provide all details related to various methods. Please search for additional information about management techniques as needed.

Fall Tasks

Search for invasives such as honeysuckle and buckthorn that still hold green leaves after others have changed color or fallen.

Cutting and treating woody non-clonal invaders (note exceptions below)

-

-

-

- Avoid times when things are wet or there is more than 3-4” of snow cover.

- Do not apply herbicide, especially water-based herbicides, prior to a precipitation event (wait at least 4 hours)

- Do not use oil-based ester herbicides (e.g., Garlon 4) during the growing season in high-quality remnants if temperature is above 60-65 degrees because of volatilization transfer

- Follow good practices such as cutting and treating all stems of the plant, apply water-based herbicide immediately after cut and oil-based soon after. Use water-based herbicide in wet areas and use a water-base or oil-base herbicide if above freezing (concentrated Glyphosate mix, 20% active ingredient, works well on species sensitive to glyphosate down to 20 degrees) or oil-based herbicide if below freezing. Many details on herbicide selection and use can be found in currently available resources, especially herbicide labels.

-

-

Cutting and treating clonal species such as sumac and aspen

-

-

-

- Requires that the entire clone be treated in most cases. Consider non-herbicide methods during other seasons (see below).

- NEVER cut any clonal species without herbicide treatment during fall or winter

- May need follow-up on some species in the following year

-

-

Basal bark spraying

Brush piling after plants have died back

Cutting coniferous trees (late fall to avoid trampling desirable plants during seed production)

Firebreak work (for winter and spring burns). In addition to other break work, mowing grass breaks for spring burns best in fall

Prescribed burning (consider timing of these and if prior management needs to be done first; for more information about prescribed burning, stay tuned for details about our annual conference which includes burn school)

Seed collecting

Seed dispersal

Winter Tasks

(some of these activities are easier and more effective with little or no snow cover)

Brush piling

Brush pile burning when snow is on the ground (add to burning piles to reduce the number of piles)

Cutting and treating woody invaders (note exceptions listed under fall and below; avoid times with extreme low temperatures)

Basal bark spraying

Cutting coniferous trees

Prescribed burning when prairies are snow-free and snow in surrounding woods (consider timing of these and if prior management needs to be done first)

Firebreak work (for winter and spring burns)

Seed dispersal (earlier is better)

Plant plugs while conditions are still moist

Early Spring

Prescribed burning (consider timing of these and if prior management needs to be done first)

Pulling woody species of small size when soil is wet.

Search for invasives with green leaves (e.g., garlic mustard) before others have leafed out. (Although shrubs like honeysuckle and buckthorn can be found at this time, do not cut and treat if the sap is flowing at a high rate).

Flame weed garlic mustard seedlings in May (where leaf litter or grassy fuels are present, do this when conditions are wet).

Pull garlic mustard and dame’s rocket before seeds start to develop.

Seeding can be done in early spring, especially if preparation for seeding includes a burn prior to seeding.

Late Spring

Girdling without herbicide treatment of trees such as aspen (some other species, but not all)

-

-

-

- Must do all trees for clonal species

- Do not use this method on black locust.

-

-

Seed collecting (disperse after collected for some species)

Summer

Double-cutting clonal woody vegetation, including sumac and young aspen (~July 1 and August 1 for multiple years; no herbicide; not black locust)

Cutting and treating woody invaders (note exceptions listed under fall and below; see comment regarding high temperatures under the “good practices” in the fall section)

Mowing invasive species (consider timing)

Firebreak work (for fall burns)

Foliar spraying (consider timing based on species herbicides)

Root-severing of monocarpic species (e.g., wild parsnip, biennial thistles)

Seed collecting

Dispersal of fresh seed from early flowering species whose seeds ripen early

Assess community health/progress towards restoration goals

Eliminating Buckthorn Without the Use of Herbicide

Eliminating Buckthorn Without the Use of Herbicide

Story and Photos by Ron Rigden

October 2, 2023

Typical regrowth of buckthorn

Buckthorn is an invasive shrub that has infested many of the forests and bluff prairies of the Upper Midwest, including Hixon Forest in La Crosse where our Coulee Region Chapter has been working to control it. It is known that cutting buckthorn without treating the stump with an herbicide causes it to resprout. It is not known how frequently or how long buckthorn must be cut before it doesn’t resprout, or if it is even feasible to kill buckthorn by just repeatedly cutting it. Friends of the Blufflands has partnered with our chapter to help answer this question by sectioning off an area in Hixon Forest with heavy growth of relatively small buckthorn plants and cutting parts of that area at different frequencies. We hope to be able to determine the minimal frequency that young buckthorn needs to be cut to eliminate it without the use of herbicide.

Hypothesis

If young buckthorn is repeatedly cut it will eventually not resprout. The minimal frequency after mid-June until the first hard frost at which this cutting must take place is unknown.

Methods

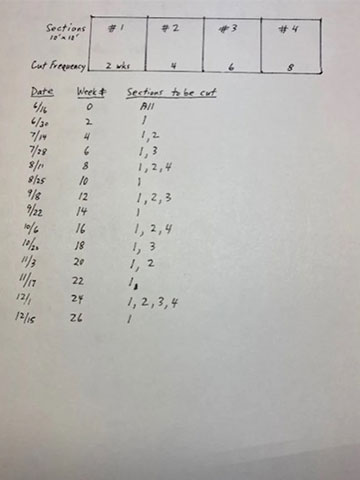

A 400-square-foot study plot was chosen for its uniformity of buckthorn growth. The buckthorn was about waist to shoulder high with the diameter of stems mostly about half to three-quarter inch or smaller. This area was cut close to the ground on June 16 with a handheld brush cutter. The cut stems were gathered and removed from the area, then a second pass was made with the brush cutter to assure that all the stems were cut. The plot was marked off and divided into four sections, each measuring 10 by 10 feet. These sections go up the slope from bottom to top. The four sections were cut at four different frequencies (every 2 weeks, 4 weeks, 6 weeks, and 8 weeks). A border was also cut around this 400-square-foot plot. The nearby uncut buckthorn was used as a control. Subsequent cuttings were done from that date until the first hard frost, which occurred on October 25, 2022. It is recognized that new seedlings from the seed bank would appear and must be taken into consideration.

Area before cutting

Cutting schedule (though the actual cutting took place near these dates due to weather or other factors)

10 x 10 feet sections marked off after cutting

On 6/16/2022 a 15 x 50 feet section on Lookout savanna, well east of an area that had been foliar sprayed the previous year and easily accessible from Savanna Trail in Hixon Forest, was chosen for its uniform growth of common buckthorn. The buckthorn was about waist to shoulder tall with the diameter of stems mostly about 0.5 to 0.75 inch or smaller. There were minimal other woody plants present, such as honeysuckle or oriental bittersweet. This area was cut with a weed wacker with a blade close to the ground, the cut stems were gathered and removed from the area, then a second pass was made with the weed wacker to assure that all the stems were cut. Then four side-by-side 10 x 10 feet areas were staked out within this 15 x 50 foot area. Down the slope and separated from the 15 x 50 area by a 3-4 foot cut buffer, a second 10 x 10 area had all the woody plants removed with the traditional cut and treat method using hand held pruners and 20% triclopyr in bark oil with surfactant and blue dye.

Study Plots Two Weeks Later on 6/30

The cuttings proceeded through the year according to the schedule with the last cutting of sections 1 and 3 taking place on 10/25/22 after which a hard frost occurred. Here are the measurements of growth in the 4 sections on this date:

Section 1

Top 5 averaged 1.5 inches of regrowh

Section 2

Top 5 averaged 2 inches of regrowth.

Section 3

Top 5 averaged 4 inches of regrowth.

Section 4

Top 5 averaged 5 inches of regrowth.

Status through the Winter

Photos taken on June 6, 2023

Section 1

Section 2

Section 3

Section 4

A view of the entire plot looking east

Conclusion:

If you’re interested in partaking in management research like this, send us a message!

Controlling clonal tree species by double-cutting

Controlling Clonal Tree Species By Double-Cutting

By Jim Rogala

Continuing on the theme of herbicide-free control methods, I’ll talk about my experience with double-cutting. Again we look to the anatomy and physiology of the species to be controlled to understand how this works [for those of you that know why double cutting works, or don’t care why it works, you can skip the next three paragraphs]. Clonal species form what looks like many plants when in fact it is a single plant with many stems. These clusters of stems often have larger older stems toward the center and smaller younger stems on the perimeter. No matter what the control method you use (mechanical or chemical), all stems of the clone need to be treated. Cutting off the stems in the winter results in the formation of new stems from adventitious nodes the next spring. Where there were tens (or hundreds) of stems prior to cutting, you might have hundreds (or thousands) after a winter cutting.

When to Cut

Cutting any plant when most of the energy stored in the roots has been translocated to above ground plant parts is advantageous. For most trees, this translocation occurs throughout the spring and early summer when it is building structures to 1) produce new energy, 2) to add to its size, and 3) for reproduction (leaves, trunk/branches, and flowers/fruit, respectively). After this annual use of energy from the roots is done, the tree begins translocating energy back to the roots at higher percentage. So, to deliver maximum hurt to the tree, cutting before energy starts going back to the roots is a good strategy. This maximum damage also minimizes prolific sprouting from adventitious nodes.

Even with a well-timed cutting, a tree still has enough energy in the roots to produce more above ground structure to assure it lives on. Here’s where the double-cutting comes in. After the first cutting, the tree needs to again use the remaining energy in the roots to build all new structures for the purpose of gaining energy (reproduction is put on hold under these stressful times). Similar to the first cutting, this second cutting is timed to coincide with maximum translocation of energy from the roots, but again not waiting past the period where a lot of energy is translocated to the roots.

I read about doubled-cutting years ago and have used it quite a bit. I generally follow the July 1 and August 1 timing for cutting but have varied it a little depending on growth in a given year (e.g., first cutting for sumac is usually after flowering). I’ve done the “cutting” with a variety of methods. I’ve used a mower if clones are large, where mowing is feasible, and the clone is not in a high-quality prairie. The point related to high quality prairie is that multiple years of repeated mowing can have negative effects on some desired species. I’ve found mowing to not be as effective, as it reduces shading of resprouts because everything gets cut. I’ve used a handheld brushcutter in native prairie areas, cutting each stem individually. It’s not as quick as mowing, but less damaging to other prairie species and better than using hand loppers to cut each stem. Loppers are effective for small clones. I’ve found that with sumac, you can actually snap off the stems in many cases (but be prepared to have the juices stain anything it gets on). Depending on the size of the stems, a Parsnip Predator can be used to cut the stems.

Where to Cut

Another variable to consider is the height of the cut. I’ve varied this as well, from ground level to 2-3 foot high. Cutting to ground level results in fleshy resprouts that can easily be second-cut with a Parsnip Predator. The really high cut was done to encourage resprouting only on the stem and to test if you get less new stems from the roots. This method allowed a second cut of a single stem, rather than the cluster of resprouts that come from the base. With this method, I found that the stem sprouts can sometimes just be snapped or stripped off, especially with sumac. The disadvantages are that some of the energy in the stem is retained, and the resprouts are not shaded by other vegetation. The method seemed to work as well as cutting lower on the stem in areas of sparser vegetation.

But Does it Work?

How effective is double-cutting on clonal species? I use it only on aspen and sumac; it’s been found to be ineffective on black locust. Because these two species are native, I’m not really all that concerned with eradication. However, I have eradicated many clones using double-cutting (with no herbicide), but most of those required several years of double-cutting. In one case, a single double-cutting killed a sumac clone. This was an older clone, so include that as one of the variables that might contribute to success when using double-cutting.

You might consider herbicides if you want more certainty in eradication. However, as Tom Brock pointed out in his management work (read here), even with herbicide it is a multi-year effort. For myself, I like the opportunity to control a native invading species without the use of chemicals. However, for the double-cutting to be effective, you must be timing the cuttings correctly, be cutting all of the stems in the clone, and continue the process as long as needed.

Read about other non-herbicide management techniques like using a Parsnip Predator, or girdling.

Controlling biennial invasives without herbicide using a Parsnip Predator

Controlling Biennial

Invasives Without Herbicide

Using A Parsnip Predator

By Jim Rogala

My recent blog post on girdling got me thinking about other herbicide-free invasive species control methods. For biennials, there are three common mechanical control methods: mowing, pulling, and cutting below the root crown. Mowing is favored for large infestations because of the daunting task of methods used on individual plants. Pulling or root severing is feasible on small infestations. For some biennials, such as sweet clover, pulling works if conditions are right. However, there are some species where pulling is not that effective, and in those cases, root severing is a better method. In this post, I’ll discuss using root severing as a method to control biennials.

How it Works

As with girdling, the control of biennials also takes advantage of the plant’s anatomy and physiology to kill plants without using herbicides. In this case, we take advantage of the inability of many biennials to re-sprout if cut at some depth below ground level. These plants typically have taproots with all the adventitious buds (the source of re-sprouting) near the soil surface, thus allowing all the buds to be removed with below-ground cutting. Technically, many of these can live more than two years (they live until they flower), but without resprouts they are dead. Typically, cutting 2” or more below the root crown will suffice, but in some cases, I’ve found it successful at even less than 2”. There are many factors that affect resprouting, such as growth stage, nutrient storage, and other simultaneous stressors (e.g., shading), so keep these in mind as you decide how deep you need to go.

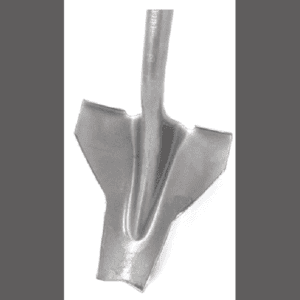

How to Cut the Crown

So, how does someone efficiently cut a root under the ground? The Parsnip Predator is a modified shovel that was designed specifically for this purpose by The Prairie Enthusiasts Prairie Bluff Chapter. Though obviously designed for wild parsnip, I’ve used it on other biennials such as sweet clover, burdock, and biennial thistles. I also find it handy to use on some annuals to minimize seed production, and for some perennials to set them back. I even use it for above ground severing of young tree sprouts when I’m double-cutting species such as aspen and sumac. I actually seldom use it as one would typically use a shovel, but rather just thrust the blade into the ground at an angle through the root of biennials or through the stems of perennials (and tree resprouts).

There are some advantages of root severing as opposed to other mechanical methods. As opposed to mowing, the severing allows the surrounding vegetation to stay intact, therefore not only leaving desirable species unharmed but providing shading of the potential resprouting biennial. Even though the repeated thrusting of the shovel is hard on the body, I find it less abusive than the constant bending over to pull biennials. And when it comes to parsnip, I like the idea of not having to grab a plant that has harmful juices in it! It can also be done under most soil moisture conditions, whereas pulling works best in moist soils.

The next time you need to address problems with biennials, consider using root severing to your potential management approaches and add a Parsnip Predator (or two!) to your toolshed.