Who We AreSylvie Rising Operations Assistant...

A Legacy of Land Stewardship Continues for a Rare Habitat in Rock County

A Legacy of Land Stewardship Continues for a Rare Habitat in Rock County

Written by Sarah Barron. Photos by Joshua Mayer

March 21, 2024

Newark, WI—As spring begins, nature lovers anticipate the first sounds of sandhill cranes and spring peeper frogs. However, habitats that can support these species and others like them have become increasingly rare. That’s why the protection and stewardship of these threatened places and the life they support is more important now than ever.

Since the early 1980s, Beloit College has been caring for Newark Road Prairie which consists of nearly 33 acres of high-quality wetland, prairie and oak savanna. To maintain its rich diversity, the land requires active stewardship consisting of frequent prescribed fires and invasive brush removal. For decades, Beloit College has had passionate volunteers, contractors and staff like Professor Richard Newsome stewarding the land. Recently, The Prairie Enthusiasts approached the college to collaborate on habitat stewardship. That relationship resulted in Beloit College generously donating the property to The Prairie Enthusiasts on March 21, 2024. The Prairie Enthusiasts will continue the site’s long legacy of stewardship, ensuring that the prairie will be a haven for wildlife for generations to come. “Newark Road Prairie is one of the most ecologically diverse areas that we are now stewarding,” says Debra Behrens, Executive Director of The Prairie Enthusiasts. “We’re grateful for the decades of care that many organizations have provided and look forward to continuing that land legacy.”

The property, which was originally protected in the 1970s by The Wisconsin Chapter of The Nature Conservancy, has been managed by college students and volunteers, Rock County Conservationists and The Prairie Enthusiasts. It is home to an incredible array of plants, insects and animals. Crayfish burrows create small mounds throughout the wetland, and rare plants draw in students and researchers. The diversity of wildlife there is so abundant that the Wisconsin DNR named it a State Natural Area in 1974.

The property has also served as a place of ecological and geological education for Beloit College students who have examined the behavior of red-winged blackbirds, monitored streams and completed floristic surveys. Yaffa Grossman, Professor of Biology with Beloit College stated, “Newark Road Prairie’s rich floristic diversity provides a glimpse of southern Wisconsin’s rich prairie heritage. Beloit College students, faculty, and staff, the Rock County Conservationists and others have engaged in many field trips, research studies and prescribed burns at Newark Road Prairie during the past 40+ years. As The Prairie Enthusiasts assume the stewardship of this site, I expect that these activities will continue and grow.” Newark Road Prairie will continue to be a place of education for the college as well as be open to the public.

All are welcomed to lace up a pair of boots and enjoy walking along the mowed path where one can observe the many birds and blooms. The Prairie Enthusiasts also encourage anyone with or without land stewardship experience to take part in caring for this special place. The immediate need is to remove invasive brush. Anyone interested in getting involved or wanting to support this work should contact The Prairie Enthusiasts at Info@ThePrairieEnthusiasts.org.

About The Prairie Enthusiasts

The Prairie Enthusiasts is an accredited land trust that seeks to ensure the perpetuation and recovery of prairie, oak savanna, and other fire-dependent ecosystems of the Upper Midwest through protection, management, restoration, and education. In doing so, they strive to work openly and cooperatively with private landowners and other private and public conservation groups. Their management and stewardship centers on high-quality remnants, which contain nearly all the components of endangered prairie communities.

Upcoming Conservation Congress-What You Can Do

Upcoming Conservation Congress-What You Can Do

Written by Tim Eisele

The annual spring Conservation Congress advisory meetings allows all citizens to vote on questions involving Wisconsin’s natural resources. Often, people think that the Conservation Congress questions are only for people who hunt and fish, but that is not the case. Natural resources belong to everyone and everyone in Wisconsin can vote on all of the questions, or on only those questions that pertain to their concerns.

This year voting will take place at in-person meetings held in every county of the state the evening of Monday, April 8, or people who want to just vote from their home can access the questionnaire from their computer and vote from April 10 through April 13.

Some of the questions involve health of the land, insects and wildlife.

A sampling of questions:

- Would you support the Wisconsin Conservation Congress advising the Department of Natural Resources Natural Heritage Conservation Bureau to request powerline companies refrain from mowing during the summer months and encourage powerline companies to work with private landowners to manage powerline vegetation that provides habitat for insects and wildlife?

-

- A specific land use question is concerned about mowing down low-growing native vegetation under powerlines during the summer nesting season.

- Milkweed is the one basic plant required by monarch butterflies, and the wintering population of monarchs reached the second lowest ever this past winter.

- Question 39 on the Conservation Congress questionnaire is aimed at urging powerline companies to not mow low native vegetation during the summer.

- Explanatory material says that although powerlines need to eliminate tall trees under powerlines, the low-growing milkweed, hazel and dogwood are used by monarch caterpillars and nesting songbirds

- Mowing in the summer not only destroys the milkweed containing monarch eggs and caterpillars, but also songbird and wild turkey nests.

- It may seem like a small thing, but powerline companies have thousands of miles of powerlines in Wisconsin, which pass over private land managed by private landowners.

-

- Do you support DNR using their resources and working with the Bluebird Restoration Association of Wisconsin to expand nesting box monitors and to help educate the public about the impact of pesticides on grassland bird populations?

-

- Another question notes that there has been a decline of 2.9 billion birds within North America since 1970, and grassland birds were declining the most by 53% over 50 years.

- The Bluebird Restoration Association of Wisconsin works to reestablish the population of the Eastern bluebird and other cavity nesting birds in the state that have significantly declined since the mid-1960s.

-

- Do you support the DNR and other conservation groups creating an awareness campaign focused on the adverse impact outdoor cats have on Wisconsin’s wild bird populations?

-

- A similar question aimed at reducing the mortality of wild birds, says that house cats let out-of-doors, kill an estimated billion birds each year in the United States. Education about the impact of free-roaming cats could change the behaviors of pet owners and reduce bird mortality.

-

-

Would you support the Conservation Congress working with the state legislature to designate the monarch butterfly as the Wisconsin state butterfly?

-

-

Another question states that the monarch butterfly has continued to decline in Wisconsin. If it were to be designated as the state butterfly, more citizens may take action to support raising monarchs.

-

-

Other questions include:

- phasing out lead ammunition in hunting with firearms by 2030

- eliminating landowner preference for 30% of spring turkey hunting permits

- prohibiting the use of wake boat ballast systems on Wisconsin lakes and rivers to help reduce the spread of invasive species

- allowing the public to legally walk directly across railroad tracks/right of ways for purposes of accessing state lands and waters

- banning the shining of wildlife in Wisconsin from September 15 through December 31.

Many questions include regulations for hunting and fishing and are asked by both the Conservation Congress and the Department of Natural Resources.

This spring’s in-person meetings will take place on Monday, April 8, one in every county of the State. Locations are often schools or municipal buildings, and locations are publicized and listed on the DNR website.

Doors will open 6 P.M for the meetings Monday, April 8, with DNR staff available at 6:30, followed by election of open positions for County Congress delegates at 7 p.m. and then voting on advisory natural resources questions presented by the DNR and Conservation Congress from 7:30 to 9 p.m.

People who prefer to vote online from their home will have that opportunity from noon, Wednesday April 10 until noon, Saturday, April 13. Using your computer or cell phone you can go to the DNR website to vote on questions, or directly to https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/about/wcc/springhearing.

Citizens can vote on all or only those questions they have an opinion on from the list of advisory questions presented by the DNR and from the Conservation Congress.

Votes must be made by noon on Saturday, April 13.

For people who want to vote and cannot attend the in-person meeting and do not have online access, they can contact Kari Lee-Zimmermann, DNR Conservation Congress Liaison, (Cell Phone: (608) 219-9134) and with enough advance notice she will mail a questionnaire, but it must be returned by the deadline of April 13.

If you have questions or would like more information, feel free to contact Tim Eisele, private woodland owner in Crawford County, at (608) 604-1933. Photos are available showing a powerline containing native vegetation, including milkweed, and the empty powerline following mowing and mulching of all the vegetation. Why am I sending this out? Linda and I were 1 of 8 people who submitted the powerline question in 8 counties in 2023. It was approved in all 8 counties and now is going statewide to all 72 counties and we feel many landowners will be interested in it.

Another Bluff Prairie Saved in The Driftless Area

Another Bluff Prairie Saved in The Driftless Area

By Sarah Barron

View of the Mississippi River from Marowski Bluff Prairie

“I’m very happy to save this unique piece of land as it represents not only disappearing habitat but also the very character and uniqueness of the Driftless Area.” — Dr. Marowski, the generous landowner preserving a prairie for future generations.

Ferryville, WI — When Dr. Marowski, a cardiologist living near Milwaukee, stood upon a steep bluff above the town of Ferryville, he was in awe of the stunning view. The Mississippi River, blue and majestic stretched below him, and to the north and south, the unique and ancient landscape filled the horizon. At his feet, he took notice of prairie flowers rarely seen any more and quickly understood the conservation value of the property.

The diversity of life this bluff prairie holds will now be stewarded forever. In December 2023, Dr. Marowski generously arranged for the protection of his 11-acre property by The Prairie Enthusiasts, ensuring the land will be stewarded and enjoyed for generations to come. Additional support from Mississippi Valley Conservancy, the Natural Resources Foundation of Wisconsin and Wisconsin’s Knowles-Nelson Stewardship Program helped make this protection project possible. Dr. Marowski also gifted The Prairie Enthusiasts with a land management endowment, which will provide resources to steward the habitat far into the future.

Stewardship of this prairie already began back in July of 2022. Working with Dr. Marowski, The Prairie Enthusiasts Coulee Region Chapter began restoration work on the bluff prairie. Volunteers removed some areas of sumac, red cedars and other aggressive vegetation from the site. There was already a healthy plant community there, with prairie plants like dwarf blazing-star and leadplant, as well as various birds, insects and reptiles that live on the site. The stewardship work that started and will continue in perpetuity will ensure this rare prairie ecosystem thrives.

This land, now named Marowski Bluff Prairie, is situated between Rush Creek and Sugar Creek State Natural Areas and contributes to an important protection corridor linking them together. Even though the remnant prairie at the site is in outstanding condition, it will need consistent land stewardship to remove and prevent tree and woody brush encroachment, which can shade out prairie plants. Part of that stewardship will be returning fire to the site using prescribed burns at regular intervals. The Prairie Enthusiasts Coulee Region Chapter invites the public to participate in upcoming work parties no matter what your experience level. Work parties will be scheduled this winter as weather permits. Additional volunteer opportunities and field trips will be available in the future. Details about work parties and field trips will be posted on the events calendar on our website at ThePrairieEnthusiasts.org.

About The Prairie Enthusiasts

The Prairie Enthusiasts is an accredited land trust that seeks to ensure the perpetuation and recovery of prairie, oak savanna, and other fire-dependent ecosystems of the Upper Midwest through protection, management, restoration, and education. In doing so, they strive to work openly and cooperatively with private landowners and other private and public conservation groups. Their 11 regional grassroots chapters of volunteers in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Illinois lead projects in their local communities focused especially on high-quality remnants, which contain nearly all the components of endangered prairie communities. Find more information at: ThePrairieEnthusiasts.org

Help The Prairie Enthusiasts steward more land, provide education and more by making a donation today!

Public Notice: We’re Applying to Renew Our Land Trust Accreditation

The land trust accreditation program recognizes land conservation organizations that meet national quality standards for protecting important natural places and working lands forever. The Prairie Enthusiasts is pleased to announce it is applying for renewal of accreditation. A public comment period is now open.

The Land Trust Accreditation Commission, an independent program of the Land Trust Alliance, conducts an extensive review of each applicant’s policies and programs.

The Commission invites public input and accepts signed, written comments on pending applications. Comments must relate to how The Prairie Enthusiasts complies with national quality standards. These standards address the ethical and technical operation of a land trust. For the full list of standards see http://www.landtrustaccreditation.org/help-and-resources/indicator-practices.

To learn more about the accreditation program and to submit a comment, visit www.landtrustaccreditation.org, or email your comment to info@landtrustaccreditation.org. Comments may also be mailed to the Land Trust Accreditation Commission, Attn: Public Comments, 36 Phila Street, Suite 2, Saratoga Springs, NY 12866.

Comments on The Prairie Enthusiasts application will be most useful by February 10th.

Empire-Sauk Chapter December Update

Small seeds planted lead to bigger things. At the end of June, Ian Michel, an employee from Diederich Tree Care LLC participated in a tour of Moely Prairie led by the stewardship team of Amy & Rick Chamberlin, Paul Anderson, and Brandon Mann. Apparently, Ian was impressed enough to report back to the owner of the company, Slater Diederich, that there were exciting things happening out on the prairie. Soon afterwards we were approached by Slater with an offer of a days’ worth of work pro bono to assist our efforts. After some internal discussion and meeting with Slater in person, we decided that removal of a large, declining cottonwood tree at Schluckebier Sand Prairie and a few smaller trees leaning heavily across the south boundary at Moely Prairie would fit the bill for a days’ worth of work.

Fast forward to October 27 when the crew arrived to accomplish the first phase, taking down the large Cottonwood tree at Schluckebier. Diederich Tree Care arrived with a crew of four, trucks, trailers, a brush chipper, and a skid steer for the task at hand and within a few, efficient hours had felled, limbed, and cut the tree. Not only that, they agreed to haul the trunk to two different offsite locations for use as firewood. The prairie was left in excellent shape. Phase 2 is planned for a later date at Moely. A big thank you to Diederich Tree Care LLC for their community involvement and work to improve our two precious Sauk Prairie remnants!

See the video of the Cottonwood coming down on our Facebook page.

Photos by Diederich Tree Care LLC

![Reaction to Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources State Natural Area [SNA] Strategy](https://theprairieenthusiasts.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/sna_reaction_pics.png)

Reaction to Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources State Natural Area [SNA] Strategy

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources recently published A State Natural Area [SNA] Strategy(1). Here I discuss one aspect of the Strategy that I applaud—the development of a formal procedure for SNA withdrawal. This is something that the conservation community needs to be talking about more. Challenges facing natural areas are increasing and changing, and some have already lost the characteristics that first merited their designation. Climate change is exerting pressure on natural communities, but passive neglect is a clear, if not dominant problem for natural communities that are fire-dependent. Frequently burned and otherwise well-stewarded sites are holding up quite well despite our present climate already departing significantly from what it was 200 years ago. Ignoring degradation of sites suffering from fire exclusion and general lack of stewardship only misleads the public and misrepresents what natural areas are. Our SNAs should be the places where we take ourselves and others on pilgrimage to receive inspiration that our best prairies, savannas, woodlands, forests, and wetlands freely give. This is fundamental to why many of us who work and/or volunteer in conservation do what we do. That inspiration has the power to compel others to join us in having a more reciprocal relationship to the land.

Franklin Savanna SNA in Milwaukee County is a good example of a site that could be considered for withdrawal. It was designated based on a regionally unique opportunity to restore mesic oak savanna that still had some persistent prairie- and savanna-associated species. However, little has been done to restore the savanna, and it continues to deteriorate. Most of its acreage presently consists of dense buckthorn under declining bur oaks with sparse ground layer vegetation dominated by weedy species. There is no fire. Franklin Savanna is certainly not a place I would take someone to show them mesic savanna. Tragically, there is not such a place in southern Wisconsin.

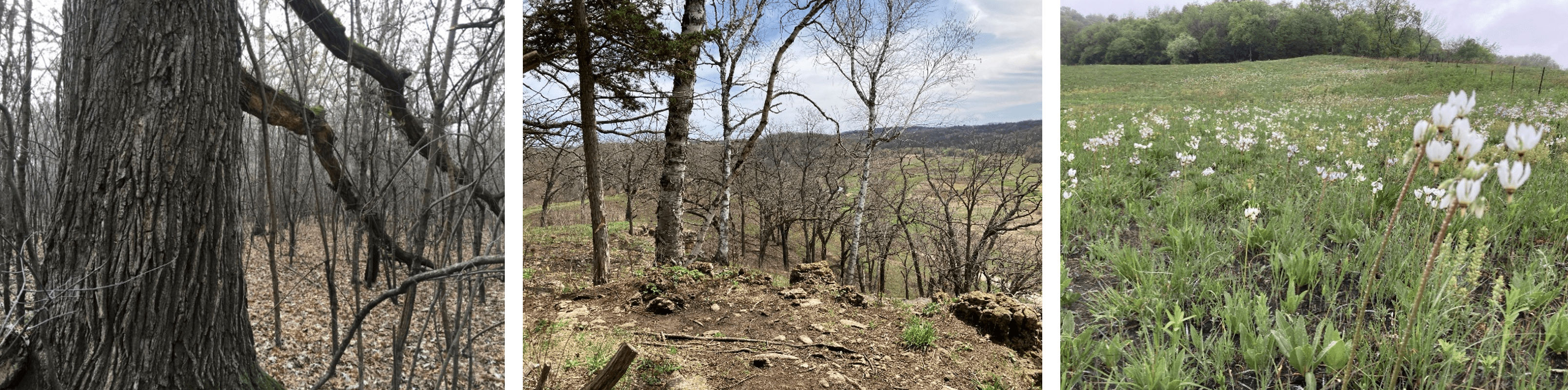

Franklin Savanna SNA (left) in Milwaukee County is a good example of a site that could be considered for withdrawal. Pleasant Valley Conservancy (center) and Black Earth Rettenmund (right) are examples of well-stewarded sites whose condition is being maintained – Photos by Dan Carter

There are other SNAs that might one day soon be considered for withdrawal, though their cases are generally less extreme. I am most familiar with SNAs near where I live southeastern Wisconsin. Karcher Springs and New Munster Bog Island SNAs (2) still retain a lot of their native biodiversity but they will continue to deteriorate without increased sustained stewardship. Cudahy Woods remains diverse for its urban location, but emerald ash borer has cut a swath right through the heart of it, and invasive species are proliferating at the expense of a rich spring flora. These places could lose much of what made them exceptional, at least regionally, within a decade or two.

None of this is to say that sites should be abandoned, even if some ultimately have SNA designations withdrawn. This is especially true where resources could be put into action. Franklin Savanna could be a very fine mesic savanna in thirty years’ time. If it were, mesic savanna inspiration would no longer require a road trip down to the Chicago suburbs. Bringing that inspiration closer to more people in the Milwaukee area would be a worthy effort that would extend beyond the site itself.

It hurts to recognize that we are still losing even legally protected natural areas when we’ve already lost so much. Acknowledging this can be downright politically fraught, so I’ll reiterate my applause of the Strategy for putting words on paper.

One group that gives us hope is the newly-formed Friends of Illinois Nature Preserves – read all about them here, and on Stephen Packard’s blog, Strategies for Stewards: from woods to prairies.

Dan Carter, Landowner Services Coordinator

[1] https://widnr.widen.net/s/zjhgzqvqdr/nh0401_lowres

[2] The island is noted for its yellow birch in a southerly location, but arguably what is more notable about it is that it also supports a unique example southern-dry mesic forest, which unlike most southern dry-mesic forests in its region doesn’t appear to simply be the result of hickory and black cherry colonizing oak savanna or oak woodland, and which unlike most upland sites in its region is minimally impacted by a history of continuous cattle grazing.