The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources recently published A State Natural Area [SNA] Strategy(1). Here I discuss one aspect of the Strategy that I applaud—the development of a formal procedure for SNA withdrawal. This is something that the conservation community needs to be talking about more. Challenges facing natural areas are increasing and changing, and some have already lost the characteristics that first merited their designation. Climate change is exerting pressure on natural communities, but passive neglect is a clear, if not dominant problem for natural communities that are fire-dependent. Frequently burned and otherwise well-stewarded sites are holding up quite well despite our present climate already departing significantly from what it was 200 years ago. Ignoring degradation of sites suffering from fire exclusion and general lack of stewardship only misleads the public and misrepresents what natural areas are. Our SNAs should be the places where we take ourselves and others on pilgrimage to receive inspiration that our best prairies, savannas, woodlands, forests, and wetlands freely give. This is fundamental to why many of us who work and/or volunteer in conservation do what we do. That inspiration has the power to compel others to join us in having a more reciprocal relationship to the land.

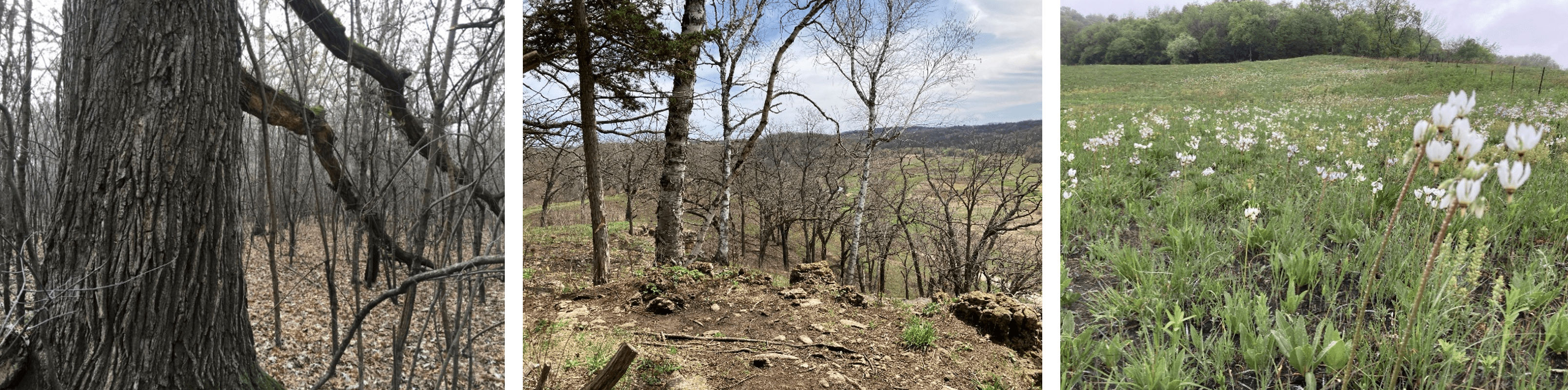

Franklin Savanna SNA in Milwaukee County is a good example of a site that could be considered for withdrawal. It was designated based on a regionally unique opportunity to restore mesic oak savanna that still had some persistent prairie- and savanna-associated species. However, little has been done to restore the savanna, and it continues to deteriorate. Most of its acreage presently consists of dense buckthorn under declining bur oaks with sparse ground layer vegetation dominated by weedy species. There is no fire. Franklin Savanna is certainly not a place I would take someone to show them mesic savanna. Tragically, there is not such a place in southern Wisconsin.

Franklin Savanna SNA (left) in Milwaukee County is a good example of a site that could be considered for withdrawal. Pleasant Valley Conservancy (center) and Black Earth Rettenmund (right) are examples of well-stewarded sites whose condition is being maintained – Photos by Dan Carter

There are other SNAs that might one day soon be considered for withdrawal, though their cases are generally less extreme. I am most familiar with SNAs near where I live southeastern Wisconsin. Karcher Springs and New Munster Bog Island SNAs (2) still retain a lot of their native biodiversity but they will continue to deteriorate without increased sustained stewardship. Cudahy Woods remains diverse for its urban location, but emerald ash borer has cut a swath right through the heart of it, and invasive species are proliferating at the expense of a rich spring flora. These places could lose much of what made them exceptional, at least regionally, within a decade or two.

None of this is to say that sites should be abandoned, even if some ultimately have SNA designations withdrawn. This is especially true where resources could be put into action. Franklin Savanna could be a very fine mesic savanna in thirty years’ time. If it were, mesic savanna inspiration would no longer require a road trip down to the Chicago suburbs. Bringing that inspiration closer to more people in the Milwaukee area would be a worthy effort that would extend beyond the site itself.

It hurts to recognize that we are still losing even legally protected natural areas when we’ve already lost so much. Acknowledging this can be downright politically fraught, so I’ll reiterate my applause of the Strategy for putting words on paper.

One group that gives us hope is the newly-formed Friends of Illinois Nature Preserves – read all about them here, and on Stephen Packard’s blog, Strategies for Stewards: from woods to prairies.

Dan Carter, Landowner Services Coordinator

[1] https://widnr.widen.net/s/zjhgzqvqdr/nh0401_lowres

[2] The island is noted for its yellow birch in a southerly location, but arguably what is more notable about it is that it also supports a unique example southern-dry mesic forest, which unlike most southern dry-mesic forests in its region doesn’t appear to simply be the result of hickory and black cherry colonizing oak savanna or oak woodland, and which unlike most upland sites in its region is minimally impacted by a history of continuous cattle grazing.