Considerations for Planting Plugs and Other Vegetative Material

Considerations for Planting Plugs and Other Vegetative Material

Article and Photos by Dan Carter, The Prairie Enthusiasts Ecologist

July 7, 2025

Poke milkweed (Asclepias exaltata) in September after being planted as a plug in May in a shady area of savanna. Plugs were propagated in this case, because only a very limited amount seed with local genetics was available.

People ask me about plugs1 from time to time, and I hear a lot of comments about them, so I’ll lay out my considerations related to the use of plugs and other vegetative plant material (roots, rhizomes, bulbs, etc.)2 in restoration and reconstruction projects. Seed is the most important means of establishing appropriate species on a site, but I personally supplement seeding with plugs and dormant roots often. Maybe I’m impatient, but I believe they can be worthwhile under the circumstances listed below:

- The species is particularly important to establish in the focal ecosystem and seed availability is limited, seed harvest is challenging or reliability of establishment from seed is low. Native violets (Viola spp.) often fit that description. Violets can be established from seed, but using some of that precious seed to produce plugs may result in more violets establishing sooner.

- You are trying to rescue genetics from a small, unprotected population or amplify a small population on a site you are restoring. In these cases, you’ll only be harvesting small amounts of seed, so producing plugs may ultimately result in more established plants.

- The species is a “matrix3” species that also spreads vegetatively by rhizomes, stolons or adventitious shoots from spreading roots. This is especially true for those matrix species for which seed availability is limited. Some examples are wild strawberries (Fragaria virginiana and F. vesca), northern bedstraw (Galium boreale), Mead’s sedge (Carex meadii) and many other long-rhizomatous sedges, sweet grass (Hierochloe odorata) and grove sandwort (Moehringia lateriflora). Other matrix species may be worthwhile to establish from plugs or to augment seeding—even if seed is more available. These include stiff sunflower (Helianthus pauciflorus), western sunflower (Helianthus occidentalis), Plains grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia gymnospermoides), prairie coreopsis (Coreopsis palmata), roses (Rosa arkansana and R. caroliniana), etc. Common matrix grasses like side-oats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula) are usually easy to establish from seed, so plugs are unnecessary.

- It’s a small-scale, residential project. In such projects, plugs for most species are a better choice than seeds. It’s easier to tell between weeds and desirable plants with plugs, and the planting will establish and look good much sooner.

There are drawbacks. First, plugs often need to be watered after their initial planting. This is especially true for plugs that are available or ready to plant in late spring. Sometimes I feel like the atmosphere knows I’ve planted plugs, so it decides not to send rain for weeks after planting. The best times to plant plugs are early spring and early autumn and when the soil is moist. However, plugs planted in early spring need to be pre-hardened against cool weather. Dormant roots, bulbs, corms or rhizomes from plants grown in propagation beds are easier because they are acclimated to the season and can be planted any time in the dormant season when the soil is workable. If I plant anything between April 1 and October 1, I assume that rain will fail. I mark the plants with flags, and plant only an amount I know I will have time to water as often as twice a week. If there is consistent soil moisture, plants will generally be well-established and need no special care after four to six weeks.

Many animals are adept at finding soil disturbances or added moisture associated with planting plugs and other vegetative material, and they often will uproot transplants to cache nuts/seeds or dig for insects or worms. I’ve even seen a video of a tiger salamander digging up freshly planted plugs on the prairie! Sometimes deer eat the tops off, and if the plugs aren’t yet rooting into the surrounding soil, they get pulled out in the process. In my experience, within a given year there tend to be particular areas where many plugs are dug up and other areas where none are dug up. One could try to fortify plants with small cages, but I’m more inclined to accept the losses and try again another time.

Planting vegetative material generally limits the amount of genetic diversity going into the site. This is especially true when roots/rhizomes of clonal species are planted, which were obtained from only one or a few clones. However, while there is more genetic diversity among seeds broadcast into a site, if seed establishment is low, the result won’t necessarily be the establishment of a population with more genetic diversity. For species that rely largely on clonal spread (e.g., Mead’s sedge), patches that establish can persist almost indefinitely despite limited genetic variation. When we harvest seed from these clonal species on remnant prairies where they’ve woven themselves through almost the entire site, we often don’t know if we are harvesting seed from one, a few or many genetic individuals unless there are conspicuous trait differences between patches or unless we do genetic testing. In such cases it is probably best to obtain material originating from at least a few sites or well dispersed parts of a single site.

Location where a stiff aster (Ionactis linariifolia) plug was planted and the top was eaten off. I was still watering it, because the crown and roots of the plant were still in the ground.

Sweetgrass (Hierochloe odorata) in September after being planted as a plug in moist, sandy savanna in May. It has already spread out by rhizomes several inches in all directions.

Plugs can be expensive, whether you buy them from a commercial source or produce them yourself. In the latter case, you’ll need a good medium for starting seeds and growing small plants, appropriate pots/flats, good artificial lighting, fertilizer and time. Vegetative material transplanted directly from outdoor propagation beds to sites is probably the easiest and generally less costly. However, it is best to remove soil and rinse roots being moved between sites, given the risk of spreading invasive species like jumping worms (Amynthas spp.) or unwanted plants, and even that won’t completely alleviate that risk. Don’t move plant material grown in soil where jumping worms are already known to occur. Finally, the most critical thing to do when you are in the process of planting plugs is to brush away some of the potting medium at the base of the shoot/top of the roots so that you can replace it with a thin layer of the soil from the site where you are planting the plug. Otherwise, moisture will wick from plug’s potting medium directly to the atmosphere and the plug will dry out very quickly. When the plug is planted in the ground, you should not be able to see the potting medium.

References

1. Plugs are generally small plants grown in flats of between 32 and 72 individual plants.

2. Except under rare circumstances and with permission, it is not ethical to dig and move wild plants. Use plants started from seeds or propagated in nursery beds.

3. Matrix species in this context are either abundant or co-dominant and woven throughout a community. A dry prairie might have a matrix of side-oats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), and Richardson’s sedge (Carex richardsonii) with a variety of other species embedded within it.

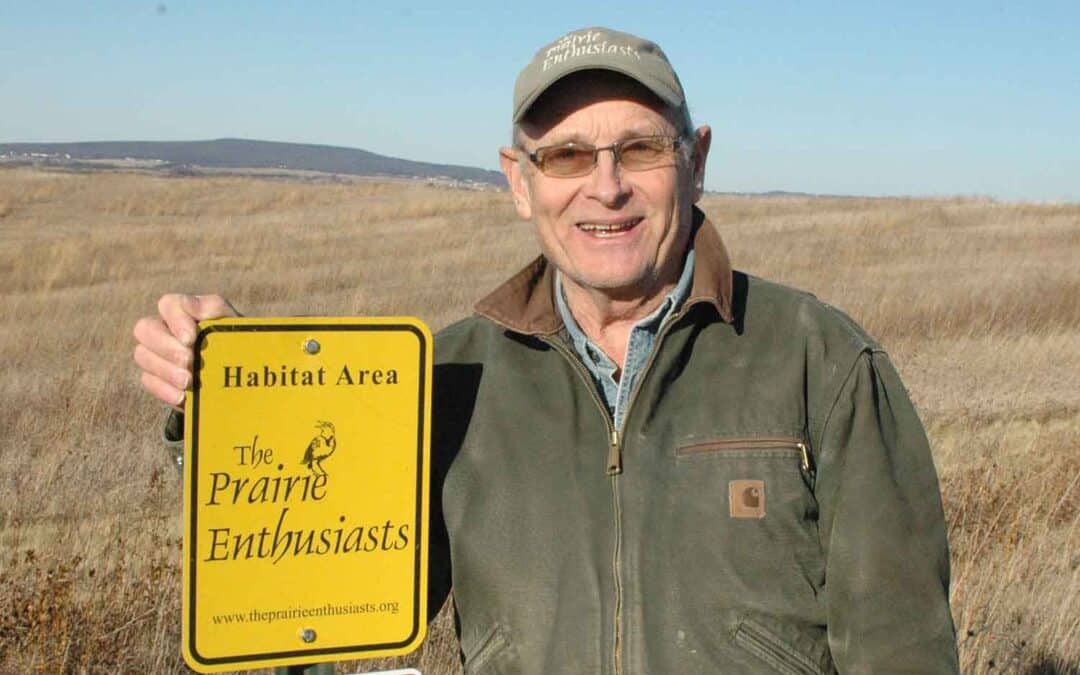

About The Prairie Enthusiasts

The Prairie Enthusiasts is an accredited land trust that seeks to ensure the perpetuation and recovery of prairie, oak savanna, and other fire-dependent ecosystems of the Upper Midwest through protection, management, restoration, and education. In doing so, they strive to work openly and cooperatively with private landowners and other private and public conservation groups. Their management and stewardship centers on high-quality remnants, which contain nearly all the components of endangered prairie communities.