We were deeply saddened to learn of the passing of longtime The Prairie Enthusiasts member Tom Brock. A true champion for prairies, Tom was also an accomplished microbiologist. Take a look at these remembrances that have been shared everywhere from our own Prairie Promoter to The New York Times.

Photo by Kathie Brock

Tom and his wife Kathie were the driving force behind the 140-acre Pleasant Valley Conservancy. Pleasant Valley is an amazing example of remnant and restored prairie, oak savanna, oak woods and wetland ecosystems. Tom, an emeritus professor of microbiology, went “all in” on restoring the property starting in the late ’90s. The Brocks were also instrumental in rejuvenating Black Earth Rettenmund Prairie, a Prairie Enthusiasts-owned property about 5 miles north of Pleasant Valley. Kathie still plays a central role in the volunteer maintenance of this site.

Tom was also involved initially with what is now the Lakeshore Preserve on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus. He helped found the Invasive Plant Association of Wisconsin. More recently, he received the prestigious UW-Madison Distinguished Alumni Award. Tom’s writings about prairie management continue to provide advice and inspiration for countless prairie enthusiasts.

Tom’s obituary can be found here.

The article in The New York Times about Tom’s achievements in the field of microbiology can be found here.

An article about Tom’s honorary doctorate from UW-Madison can be found here.

By Willis Brown

What do The Prairie Enthusiasts member and emeritus professor Tom Brock have in common with rock-n-roll star Steve Miller? In addition to never hearing of the other, they both were awarded Honorary Doctorate degrees from UW-Madison in May.

Tom received the degree for his pioneering work on thermophilic (heat-loving) bacteria he had isolated and characterized from the hot springs of Yellowstone National Park. He was also recognized for the work he and his wife Kathie Brock did in the restoration of their property, Pleasant Valley Conservancy. In a relatively small area (140 acres) they have restored several ecotypes- wetland, prairies, oak savanna and oak woods.

(Miller, as you might suspect, was honored for his music.)

In 1980 and 1984, Tom and Kathie Brock purchased the PVC property in two separate transactions primarily for recreation. Sometime later, when Kathie was volunteering for The Nature Conservancy, she heard about oak savannas – the critically endangered ecosystem once common in southern Wisconsin.

Tom also recalled seeing side-oats grama on the property and remembering it was a prairie plant. The presence of

large bur and white oaks with the prairie plants suggested PVC once was an oak savanna. Overtaken by honeysuckle and buckthorn, and other invasives, the Brocks turned their property from recreation to re-creation of the oak savanna and prairie.

They went all in starting in 1997, going so far as to hire the town of Vermont crew for a week to remove trees along the south slope below a prairie remnant (still referred to as Kathie’s Prairie). They also had their first prescribed burn that year and hired some additional help. Soon after, in 1999, they hired Paul Michler and myself to cut and treat buckthorn. Our equipment in those days was marginal – one small Stihl brush cutter, a spray bottle of Roundup and a Geo Tracker – all borrowed from the Brocks.

In those early days, Kathie would sometimes locate desirable species along nearby roadsides and collect the seeds. One day she found a new species for us to collect. Before spreading the seed, she took a sample to Madison for positive identification. That proved fortunate as this was the first time any of us had encountered Japanese hedge-parsley.

Rather than burning large logs from the cleared trees, the Brocks would leave logs by the side of the road for neighbors to take for firewood. Some cherry and walnut logs were given away for lumber.

If you visit PVC, you may notice a relatively high number of paper birch in a fire-dependent area. Kathie likes these trees, so the area around them are cleared to avoid damage by fire. Happily, the birch seem to be good habitat for redheaded woodpeckers, a state endangered bird.

Tom and Kathie treated this property like a huge experiment. They kept extensive notes and have taken numerous photographs over the years. The property is divided into several management areas. A plant species list was prepared initially with about 300 species identified. A plant survey in 2008 identified 493 species present at PVC.

A geology professor was invited to come out to describe the geology. Once most of the invasive trees were removed, all trees over 10 inches DBH (a forestry term describing diameter at breast height) were tagged and geolocated. Over 4,000 trees were mapped this way and data entered as to size, species and whether dead or alive. This data was useful in showing the extent of bur oak blight at PVC, which Tom reported in the April 2018 edition of The Prairie Promoter.

In addition, many trees were present in aerial photos from the 1930s. Some of the larger oaks have been aged, and the oldest is over 200 years old. For several years, starting in 2003, Tom and Kathie hired summer interns to continue the restoration work. Always the professor, Tom would present a lecture on various topics on restoration during lunch. They are also willing to have research done on their land (with approval), including using plant hormones to control reed canary grass, or the study of great blue lobelia.

Tom conducted his own research on controlling invasives such as sumac and honeysuckle. He has published results of his work in Restoration Ecology and The North American Prairie Conference Proceedings in addition to The Prairie Promoter. They are always willing to share their experiences and show their results to various groups such as Madison Audubon Society, Blue Mounds Area Project, and Land Trust Alliance among others. They have guided tours of their property annually on Labor Day. They also host group tours to identify birds, butterflies and other fauna and flora.

Over the years, Kathie has propagated desirable plants from seed that were not present or present in small numbers such as purple milkweed, a state endangered plant. Purple milkweed appeared on their property shortly after initial clearing of non-savanna species. She transplanted the seedlings to appropriate areas, flagged them to determine survival rates and watered them if needed. In addition, Kathie has compiled data and produced a table of the best time of year to collect seeds from individual species.

They’ve collected and/or traded seeds with Goose Pond (Madison Audubon), Swamplovers and others. The result is a fabulous example of oak savanna (with added birches), remnant goat prairie, wetland, restored prairie and oak woodlands. The property was dedicated a State Natural Area on June 6, 2008. While Tom and Kathie received some money from grants, they paid for this beautiful restoration project essentially with their own money from which we all benefit and are grateful.

Salvaging Black Earth (Rettenmund) Prairie

About five miles north of PVC is Black Earth Prairie. It’s a prairie remnant of spectacular diversity. Previously owned by The Nature Conservancy, BEP was suffering from benign neglect because, as a relatively small property for TNC, there were only 1-2 volunteer work parties each year. The southern end of this 17-acre prairie had been severely taken over by brush.

Tom and Kathie gave TNC money in 2003 to have the brush removed by contractors. They also restored the area by the entrance, which had become mainly brome grass. They then took over stewardship of the prairie in 2005 by hosting monthly work parties to continue controlling invasives, collecting seeds and managing controlled burns. Due to the unusual configuration of the property, burning only within the boundary was difficult, so they convinced the neighboring landowner to include part of his pasture in the burn unit. This produced an unintended benefit with the appearance of copious little bluestem and butterfly milkweed in the pasture. TNC transferred BEP to The Prairie Enthusiasts in 2007. Tom and Kathie are the site stewards to this day.

Tom keeps a blog about PVC, found at pleasantvalleyconservancy.org. Tom recently compiled a history of the work performed over the years, entitled Restoring a Fragile Landscape. The two volumes can be readily downloaded from their website. While the number of pages may seem daunting, they consist primarily of photographs, and one can quickly discern how much Tom loves controlled burns. PVC is open to the public. There are several hiking trails and even a boardwalk to access the wetland. Check it out if you can.

Professor Teresa Schueller, Director of UWM at Waukesha Field Station (left) and St. Croix Valley Chapter member and TPE board representative Evanne Hunt (right) (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Professor Teresa Schueller, Director of UWM at Waukesha Field Station (left) and St. Croix Valley Chapter member and TPE board representative Evanne Hunt (right) (Photo by Caleb DeWitt) Tom Zagar, Ecologist and Burn Boss for the Glacial Prairie Chapter. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Tom Zagar, Ecologist and Burn Boss for the Glacial Prairie Chapter. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt) Professor emeritus Marlin Johnson leads a history tour. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Professor emeritus Marlin Johnson leads a history tour. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)  Introduction to the wood-fired kiln during the annual picnic field trips. (Photo by Ron Lutz II)

Introduction to the wood-fired kiln during the annual picnic field trips. (Photo by Ron Lutz II) More discussion of how the prairie restoration process began (Photo by Ron Lutz II)

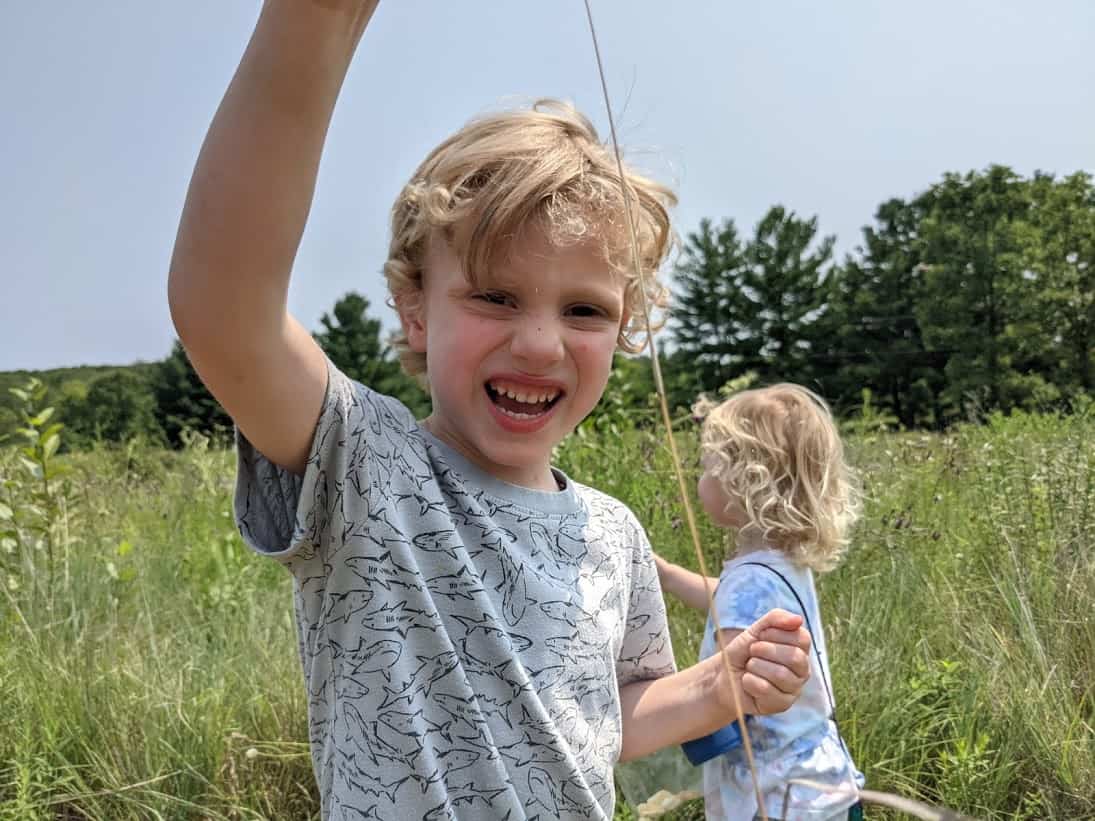

More discussion of how the prairie restoration process began (Photo by Ron Lutz II) Young prairie enthusiasts showing off their discoveries and enjoying the prairie. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Young prairie enthusiasts showing off their discoveries and enjoying the prairie. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

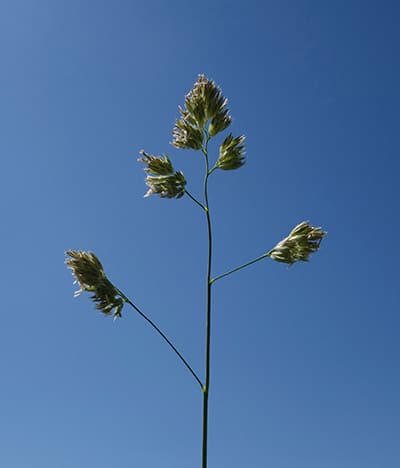

Hoary puccoon with friend. Photo by Rob Baller

Hoary puccoon with friend. Photo by Rob Baller

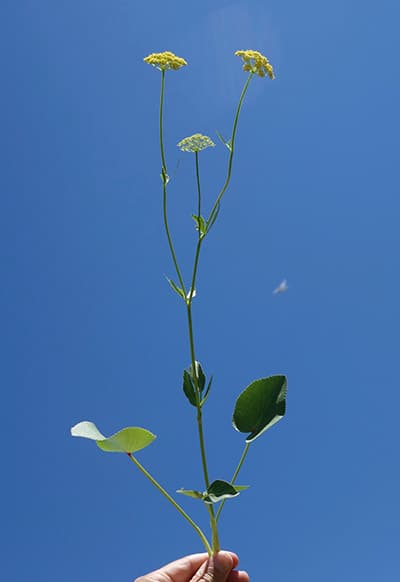

Blue sky hairy puccoon. Photo by Rob Baller

Blue sky hairy puccoon. Photo by Rob Baller