by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Nov 11, 2021 | News

Lonetree Farm, in rural Stockton, Illinois, gets busy this time of year with NIPE’s prairie seed mixes. Staff and volunteers spend hours picking native plant seeds from area prairies and savannas, separating seeds from the rest of the plant, drying seeds, and then sorting into their proper mixes for seeding and overseeding elsewhere.

Earlier this fall, NIPE received two and a half large lawn bags of common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) to help with these efforts. This is the milkweed that is so important to the Monarch butterfly life cycle. To use the seed in NIPE’s prairie seed mixes, it must be removed from the pods and de-fluffed. Paid staff and volunteers spent a total of 55 hours at Lonetree cleaning three wheelbarrows full of pods. The result was a little over eight pounds of clean seed.

(Photos of the Asclepias de-fluffing project: from wheelbarrows full of seed pods to de-fluffing to clean seed. Photos by Rickie Rachuy.)

In late September, NIPE’s Jim and Rickie Rachuy gave members of the Lake Carroll (Illinois) Prairie Club a tour of the rare plant gardens at Lonetree Farm. The tour also included time spent in the seed shed and greenhouse (currently housing more prairie plant seeds awaiting milling and bagging). Club members were allowed to process a few of their own collected seeds on the hammer mill in the seed shed.

In the Rare Plant Gardens at Lonetree Farm (photo by Pam Richards)

Working the Hammer Mill (photo by Pam Richards)

by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Nov 11, 2021 | News

Moely Prairie has had a presence on Instagram (@moelyprairie) and Facebook (For the Love of Moely Prairie) for the last several years, and during that time, my fellow volunteers and I have connected with many nature lovers around the world. One follower who I have come to know quite well is Stefan van Norden, the producer of a podcast called Nature Revisited. Earlier this spring, he asked if I would be open to doing a podcast about Moely Prairie. At first, I was a bit hesitant; my family and I have only been doing prairie restoration for about 5 years, and although we have certainly learned a lot about prairies in that time, we still don’t feel like we qualify as “experts” to speak with authority about prairie restoration.

Stefan explained that he was delighted by the photos on our Instagram page depicting our daily discoveries and was intrigued by our restoration efforts on this true remnant prairie. Sensing my hesitancy, he suggested that we forego the traditional podcast interview and instead create an episode that highlights the voices of the land owners, educators, students, conservation experts, and volunteers who appreciate, study, and work to restore Moely Prairie. Stefan’s excitement and vision made it an easy challenge to accept.

Over the summer, I conducted several on-site interviews. Barbara Moely, who owns the land with her sons and who donated the conservation easement that protects Moely Prairie in perpetuity, recorded her testimony from her home in California. My husband, Rick, went to work crafting a poetic narrative to highlight some of the natural and cultural history of the land, including the “where” and the “what” that make remnant prairies like Moely Prairie so special.

Week by week, I would send our audio files to Stefan, who wove parts of them into Rick’s narrative, and music created by Ben Cosgrove. We were given permission to use the song, “Cairn” from Ben’s most recent album, The Trouble with Wilderness. When I first heard the song, it immediately conjured pictures in my mind of Moely Prairie in its many seasons. We all agreed it would be the perfect accompaniment to the voices of Moely Prairie.

We are delighted with the final results and hope you, too, have a chance to listen. Find the podcast by subscribing to Nature Revisited on your favorite podcast streaming platform, on the Nature Revisited YouTube page, or at their website. As of this writing, the Moely Prairie episode has reached more listeners in the first 24 hours than any other podcast Stefan has produced. It’s a wonderful testament to the love people have for Moely Prairie and for all prairies in general.

by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Aug 31, 2021 | News

Learning about how to protect turtle nests. (Photo by Martha Querin-Schultz)

The Southwest Chapter of The Prairie Enthusiasts held a Wisconsin turtle workshop on Saturday, June 26, 2021, at Jack Kussmaul’s beautiful home near Woodman, Wisconsin.

“Taking Time for Turtles” was conducted by Dr. Rebecca Christoffel who is co-director of Turtles for Tomorrow, a non-profit organization devoted to protecting Wisconsin turtles.

Our enthusiastic group of 18 learned all about Wisconsin’s turtles from Dr. Christoffel, including who they are, how to identify them, where they’re found, and how they are managed and conserved. The group spent the morning in the classroom, learning about Wisconsin’s turtles and how to identify them including some practice identifications. Wisconsin has eleven turtle species. Ten are aquatic or semi-aquatic and one is strictly terrestrial (land dwelling).

Host Jack Kussmaul, along with guest speaker, Dr. Rebecca Christoffel, co-director of Turtles for Tomorrow). (Photo by Martha Querin-Schultz)

In the afternoon after lunch, we went to Jack’s amazing property which is along the Wisconsin River, searching for turtles and signs of turtles, and we learned what we can do to protect turtle nests found on our properties.

While we were out walking, a couple of wild turtles came right up on to Jack’s property to lay eggs. We also were able to get up close and personal with Dr. Christoffel’s “Ambassador Turtles” that she uses in her teachings. The group had the chance to meet and hold two of the endangered and threatened turtle species in Wisconsin, the wood turtle and ornate box turtle.

Thank you to Jack Kussmaul for hosting and thank you, Dr. Christoffel, for teaching us so much!

Article by Martha Querin-Schultz

by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Aug 31, 2021 | News

Some attendees trying to determine a species of native bumblebee (Photo & article by Susan Lipnick)

On June 27, biologist Bev Paulan treated Northwest Illinois Prairie Enthusiasts members and guests to the presentation “Native Plants Need Native Pollinators” at The Prairie Enthusiasts Hanley Savanna in rural Hanover, Illinois. The event, originally scheduled for late June 2020 but postponed because of COVID, was well worth the wait.

Topics included the following:

– Some history as to how native plants and native pollinators have adapted to each other and how the decline of one is contributing to the decline of the other in various areas of the world;

– The kinds of local native plant pollinators, which include bumblebees, wasps, flies, butterflies, moths, beetles, and birds. In other areas, bats and people are important pollinators;

– The needs of local native pollinators, including specific food and water sources, appropriate nesting sites, and overwintering sites;

– The dangers certain retail plants present to native pollinators, including cultivars or hybrids of native plants, nonnative plants, pesticides bred into GMO-modified plants;

– Problems resulting from efforts to boost populations of the nonnative honey bee; and

– Efforts home gardeners and prairie enthusiasts alike can take to boost populations of native plants. Bev also provided a list of “superfood” native forbs as well as the top five native tree species that support 90% of our local butterflies and moths. You can find This triptych of useful information on NIPE’s Facebook page, July 1, 2021 post.

After the presentation, attendees took the opportunity to ask questions and explored the prairies, trying to identify native pollinators on native plants.

Biologist Bev Paulan, presenter. (Photo by Susan Lipnick)

by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Jul 28, 2021 | News

“Success seems to be largely a matter of hanging on after others have let go.” William Feather

People who are passionate about prairie restoration are a rare breed. However, as the number of these prairie warriors grow, so too will the numbers of successfully grown rare and endangered plants in our states. We recently heard about some tiny successes with rare plants on a small farm in Illinois that are huge reasons for celebration.

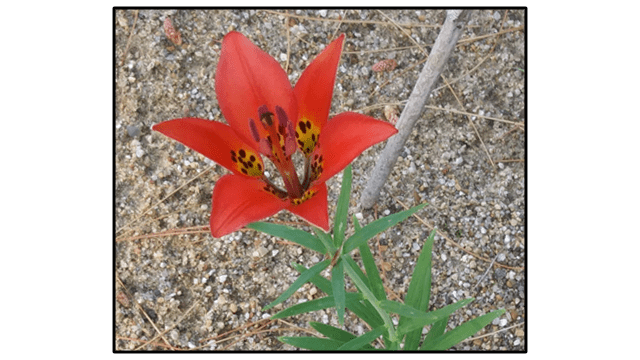

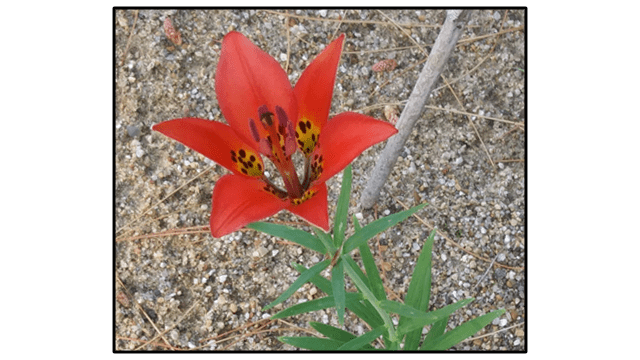

Wood Lily blooming – Photo by Rickie Rachuy

Where others might plant a seed and just move on if a plant didn’t grow, prairie enthusiasts often find the most rare or endangered plants and work for years to get just a single bloom on one plant. It is this grit and determination that will, over time, make an incredible difference in ecosystems across the upper Midwest.

One such story is unfolding in Stockton, Illinois. NIPEs Rickie Rachuy is thrilled to share some exciting success stories in the rare plants garden at Lonetree Farm.

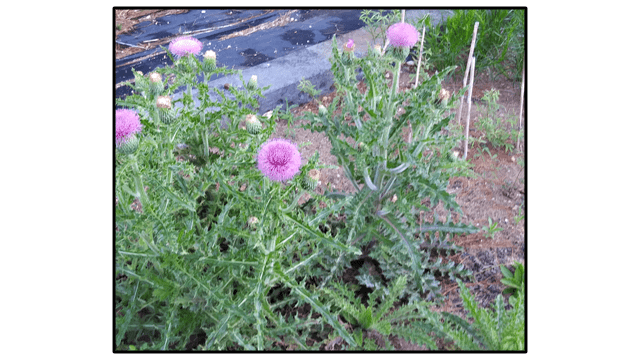

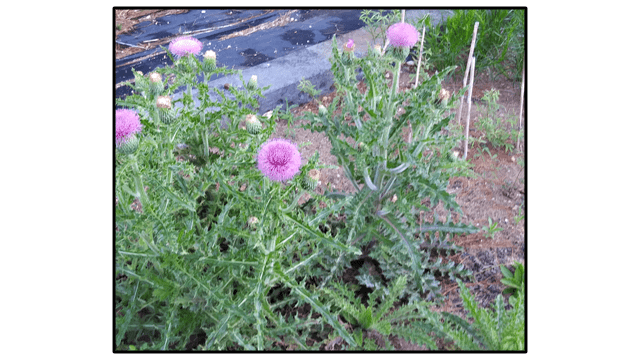

Hill’s Thistle – Photo by Rickie Rachuy

– The first blooms on Asclepias purpurascens, started from seed in 2015

– The first seedlings of Gentianella quinquefolia after three years of trying to get wild-harvested seed to germinate

– The first flowers on Lilium philadelphicum (wood lily) from seed donated by Kathie Brock after the initial seedlings were uprooted by raccoons in 2017

– The first flowers on Circium hillii (Hill’s thistle) from seed donated by Tom Mitchell in 2019

– Several healthy Clematis pitcherii plants from cuttings taken from the only known plant in northwest Illinois

– One seedling of Clematis occidentalis, from Prairie Moon seed started Feb. 1, 2020

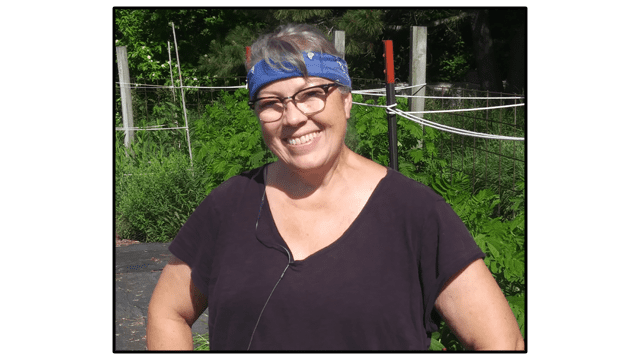

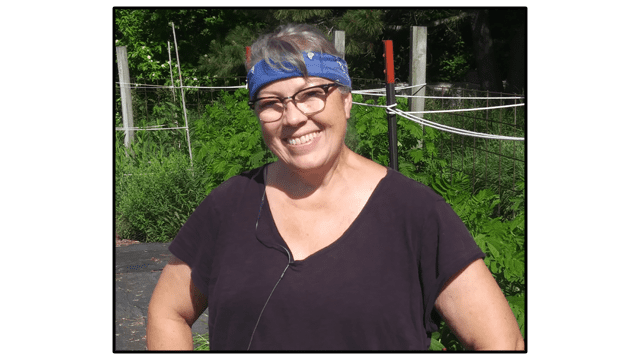

Karen Reed, newest addition to the NIPE team, and garden/seed shed helper. (Photo by Rickie Rachuy)

Thank you for sharing this great news, Rickie. While to the general population, these may appear to be little events, in the world of prairie restoration, these are some moments to truly treasure and celebrate. We can’t wait to have an update a year from now to hear how things are going.

Do you have some success stories you would like to share? Please send those to ksolverson@theprairieenthusiasts.org for possible inclusion in one of our future newsletters.

by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Jul 28, 2021 | News

There couldn’t have been a more idyllic scene for The Prairie Enthusiasts picnic and annual meeting. Basking in the glow of a perfect summer day, members gathered on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 at the UW-Milwaukee Field Station at Waukesha to learn and celebrate together. There was a palpable energy, a feeling of hope permeating the day, given all that has been accomplished in the past year. After a year of working independently in the field under COVID-19 restrictions, it was a welcome day of celebration. This day was all about reconnecting our prairie community through conversation, sharing, education and the passion that is at the heart of all we do.

Professor Teresa Schueller, Director of UWM at Waukesha Field Station (left) and St. Croix Valley Chapter member and TPE board representative Evanne Hunt (right) (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Professor Teresa Schueller, Director of UWM at Waukesha Field Station (left) and St. Croix Valley Chapter member and TPE board representative Evanne Hunt (right) (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

This year, the Glacial Prairie chapter of The Prairie Enthusiasts hosted our event. Many thanks to the volunteers who put in long hours to pull this together, as it is no small task. Members gathered for a potluck followed by a speaker from each one of the chapters.

Tom Zagar, Ecologist and Burn Boss for the Glacial Prairie Chapter. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Tom Zagar, Ecologist and Burn Boss for the Glacial Prairie Chapter. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

After lunch, it was time to fill our minds with educational tours. The tours were a great success and filled with incredible conversation. Marlin Johnson, the resident manager of the 98-acre field station for 45 years, gave a tour and discussed the process of how a dedicated group of individuals were able to convert fields into a sustainable prairie/savanna.

Professor emeritus Marlin Johnson leads a history tour. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Professor emeritus Marlin Johnson leads a history tour. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Bill Schneider led an Aldo Leopold tour focused on Leopold’s use of prairie/savanna plants and animals to make a philosophical statement. There was also an opportunity to visit a unique wood-fired kiln, built with more than 8,000 bricks, which was modeled after an ancient Japanese Anagama kiln.

Introduction to the wood-fired kiln during the annual picnic field trips. (Photo by Ron Lutz II)

Introduction to the wood-fired kiln during the annual picnic field trips. (Photo by Ron Lutz II)

More discussion of how the prairie restoration process began (Photo by Ron Lutz II)

More discussion of how the prairie restoration process began (Photo by Ron Lutz II)

The prairie was teeming with life, and the perfect setting for our time together. Walking among the ancient oaks, members were drawn to one particularly majestic specimen. Reconnecting with the oaks, the plants and living creatures of the prairie, and the people who make this all possible gave everyone a renewed sense of purpose as we prepare for the next season of prairie restoration and management.

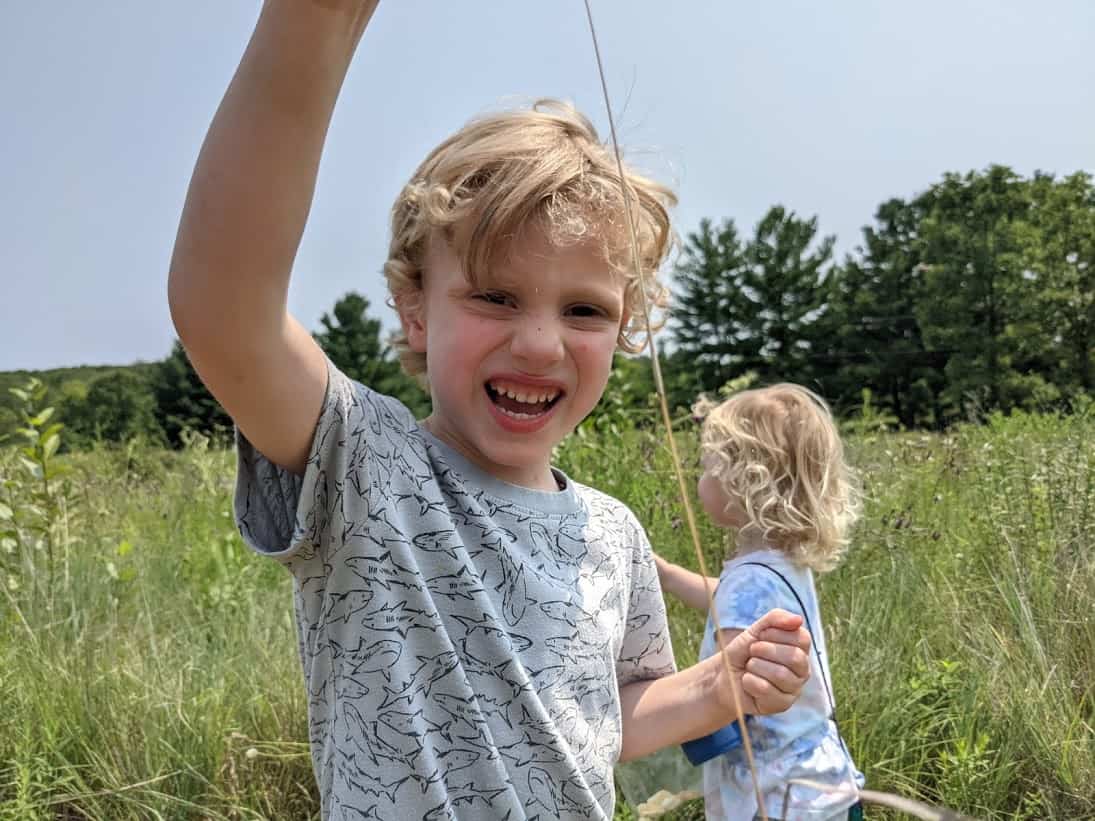

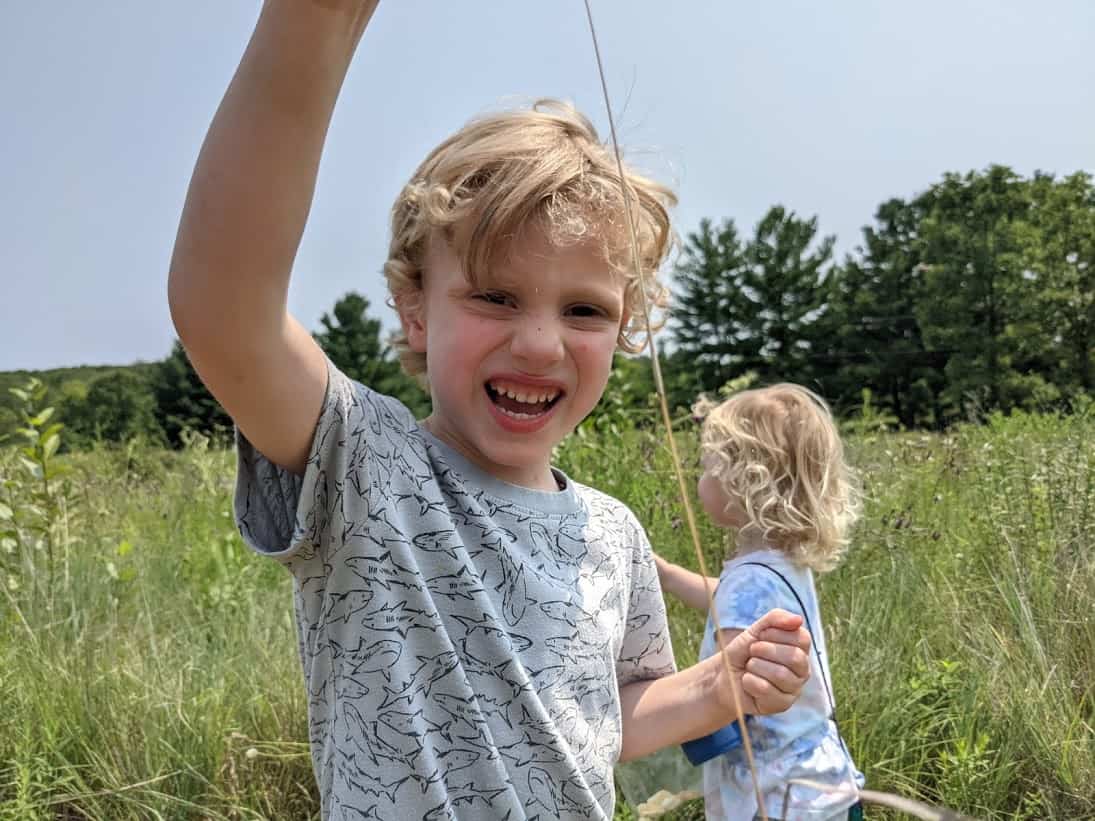

Young prairie enthusiasts showing off their discoveries and enjoying the prairie. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Young prairie enthusiasts showing off their discoveries and enjoying the prairie. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Just as the prairies come back stronger than ever after a fire, we also look forward to a year of tremendous growth in the coming year.

Professor Teresa Schueller, Director of UWM at Waukesha Field Station (left) and St. Croix Valley Chapter member and TPE board representative Evanne Hunt (right) (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Professor Teresa Schueller, Director of UWM at Waukesha Field Station (left) and St. Croix Valley Chapter member and TPE board representative Evanne Hunt (right) (Photo by Caleb DeWitt) Tom Zagar, Ecologist and Burn Boss for the Glacial Prairie Chapter. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Tom Zagar, Ecologist and Burn Boss for the Glacial Prairie Chapter. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt) Professor emeritus Marlin Johnson leads a history tour. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Professor emeritus Marlin Johnson leads a history tour. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)  Introduction to the wood-fired kiln during the annual picnic field trips. (Photo by Ron Lutz II)

Introduction to the wood-fired kiln during the annual picnic field trips. (Photo by Ron Lutz II) More discussion of how the prairie restoration process began (Photo by Ron Lutz II)

More discussion of how the prairie restoration process began (Photo by Ron Lutz II) Young prairie enthusiasts showing off their discoveries and enjoying the prairie. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)

Young prairie enthusiasts showing off their discoveries and enjoying the prairie. (Photo by Caleb DeWitt)