by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Mar 5, 2021 | News

A conference tradition continues! The online format of our 2021 conference let TPE’s amazing photographers show off their work to more people than ever. Read on to see who won.

We received entries in five categories: people, seasons, flora/fauna, landscape and wabi-sabi (the beauty of transience or imperfection). Avid photographer and contest judge Jerry Newman narrowed each category down to one photo (thanks, Jerry!). During the conference, attendees voted for their favorite to pick the ultimate winner.

In the People category: “What Pandemic?” by Rob Baller

In the Seasons category: “December at Dower Prairie” by Steve Hubner

In the Flora/Fauna category: “Great Spangled Fritillary on Hill’s Thistle” by Eric Preston

In the Wabi-Sabi category: untitled photo by Ben Behrens

In the Landscape category: “Sedge Meadow Wildflowers” by Gary Shackelford

Congrats to STEVE HUBNER for taking first place! Look for his photo on the cover of our next Prairie Promoter newsletter.

by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Nov 5, 2020 | News

Here’s a recap of Driftless Area phenology from the past month, written by our very own Pat Trochlell. Pat’s inspiration comes from her career as a wetland ecologist with the Wisconsin DNR. She and her husband, Ken Wade, live near and are stewards of TPE’s 30-acre Parrish Oak Savanna, a diverse woodland ecosystem of over 240 native species.

Follow our Facebook page to read Pat’s column once a week.

1 October 2020

Autumn is well underway, with trees turning bright colors. In southern Wisconsin, a few tree species – ash, aspen, hickory and maples – are red, yellow, and orange, but the oak-rich landscape is still predominantly green. Some understory plants, like Indian grass and staghorn sumac, also turn brilliant colors. Another plant that is now very colorful is Virginia creeper or woodbine (Parthenocissus quinquefolia). This plant is a climbing vine with palmately compound leaves. It is a strong climber, with tendrils that form an adhesive disc when they come in contact with a support. It is also our only species besides poison ivy that develops short roots along the vine to hold onto tree trunks. It’s also found climbing on human-constructed structures and rock walls.

Woodbine on sandstone wall. Photo by Pat Trochlell

The woodbine in my photograph is growing on a tall vertical wall of sandstone. Using a nifty app called Rockd, I was able to determine the type and age of the sandstone formation. It is Cambrian-age sandstone from the Tunnel City Formation, which is approximately 495 million years old. The Rockd app is a great tool developed by UW-Madison geologists. You can download the free app onto your mobile phone. As long as you have cell reception, the app can provide information about the geology and rocks in the areas that you visit.

8 October 2020

Signs of autumn continue with oak trees turning rust-colored, the scent of falling leaves, flocks of white-throated sparrows singing in the woods, and prairie plant seeds piling up in sheds and barns across the area. At TPE’s Mounds View Grassland, seed collecting started around the first of June when pasque flower seeds were ripe. Volunteers will continue into early November to harvest seed from the last remaining asters and stiff gentians. Last week, we collected boneset and mountain mint; this week, we collect prairie cordgrass and rough blazing-star.

Mounds View is just one of TPE’s many sites where seeds are harvested, processed, mixed, and stored for planting. Over the season, about 50 people show up for collecting, but the number of people has increased this year. This is probably due to the current need for us to get outside and also because TPE is reaching out to more people. Last Sunday, a record high of 17 people showed up to help with the harvest on a beautiful sunny day.

How many species are collected? Rich Henderson estimates that at Mounds View about 150 plant species are harvested, though not all in every year. Volunteers collect 300 to 400 pounds of seed with a “street value” of $100,000 to $150,000!

The monetary value of the seed is high, but the value to the prairies and other natural areas under restoration is higher. Perhaps the most important value, though, is to those of us who help collect and process the seed. We can watch the progress over time as an old cornfield or pasture is restored into the yellow and purple wildflowers and sea of bluestem that make up a tallgrass prairie. We can say that we played a part in this amazing transformation.

Seeds drying in a TPE-owned barn. Photo by Pat Trochlell

Jan Ketelle searches for western sunflower gone to seed. Photo by Pat Trochlell

15 October 2020: Asters (again!)

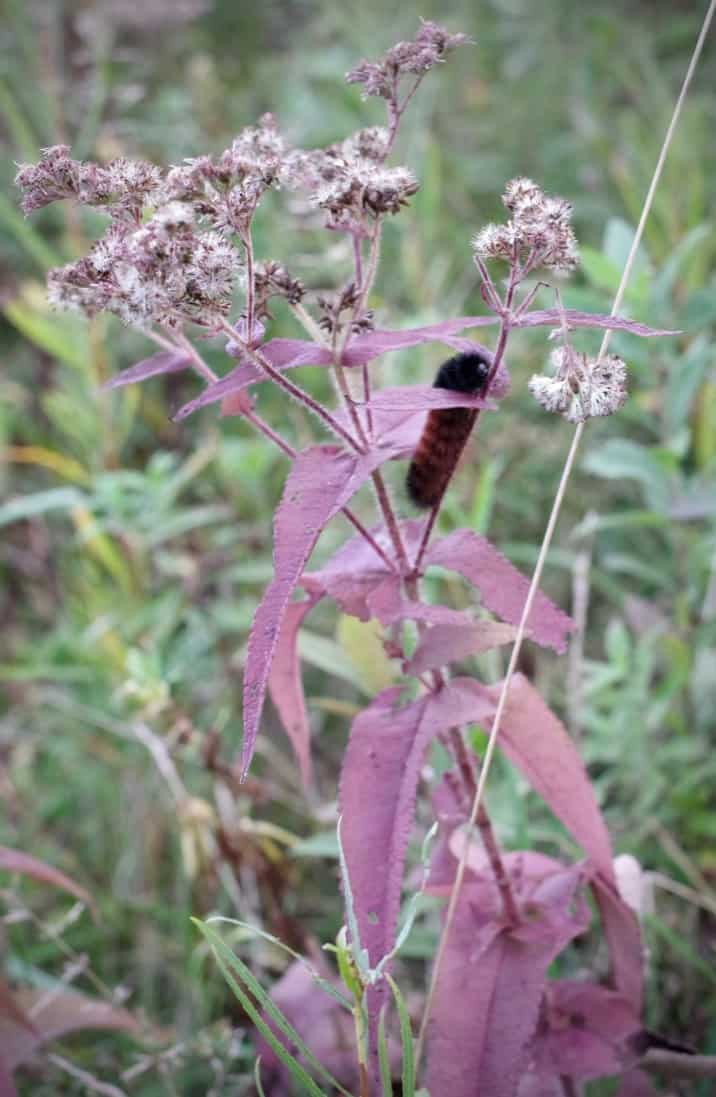

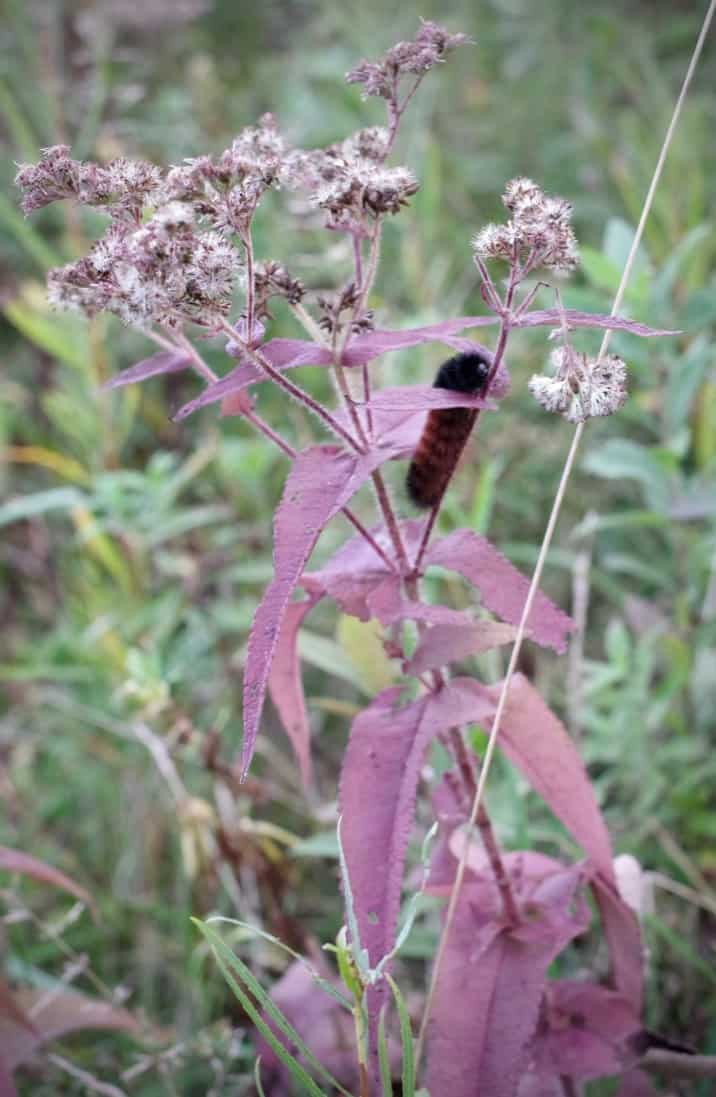

Asters are again (or still) in the spotlight for this week. We still have some species continuing to bloom, despite the colder weather and shorter day lengths. But most of them are showing signs of senescence. One species I hope to harvest seeds from along the hilly roadsides at this time of year is the flat-top aster (Doellingeria umbellata). When it blooms in late summer, the plant has numerous white flower heads in a flat-top cluster. It has many 3- to 6-inch leaves arranged alternately along the stem. At this time of year, the fluffy seed is ripe and ready to collect.

I associate this species with northern wetlands, especially in ditches along roadsides where it can be quite common. However, the plant is found throughout Wisconsin, including in the Driftless Area. Though mostly found in wetlands, it also grows in uplands. The range of habitat types in the Atlas of the Wisconsin Prairie and Savanna Flora lists “marshy, swampy or peaty ground, also in sandy or rocky uplands (such as bracken grasslands), north of the Tension Zone in spruce-cedar-ash swamps, moist fir-yellow birch-hemlock woods, and second-growth aspen, white birch, pine or red maple stands, edge of tamarack or sphagnum bogs… in the south …in fens, low prairies, sedge meadows, shrub cars, openings in low sandy woods, drained, burned or cut-over lowlands, margins of tamarack bogs and cranberry marshes, weedy in drainage ditches, roadsides and old grassy fields.”

With that broad range of habitat types, it seems capable of tolerating many conditions. But it is not a species that I have had much luck establishing from seed, despite my efforts. Maybe this year…

Sky-blue aster and a cold bumblebee. Photo by Pat Trochlell

22 October 2020

What a difference a week makes! Vibrant-hued oak trees are turning brown and losing leaves, which cover the forest floor. Weather changes are bringing rain and, in some areas, record early snowfall. Many migrating birds, like the pine siskins which were feeding heavily on stiff goldenrod seeds, have moved south. So it’s nice to see the occasional late-blooming flower, such as biennial gaura (Oenothera gaura). The plant is a mesic prairie species in the evening-primrose family. The name “gaura” comes from the Greek word gauros, meaning proud. The name is apt, as the plant grows up to 7 feet tall with numerous showy white flowers that turn pink as they age.

Late-blooming gaura. Photo by Pat Trochlell

Fall is a good time to look for signs of springs and seeps. As the vegetation senesces, more ground is exposed. In areas where there is standing water you may see signs of groundwater influence, such as the presence of iron bacteria where soluble ferrous (reduced) iron leached from rocks discharged with the groundwater. Iron bacteria are thread-like cells that oxidize the ferrous iron to ferric iron for energy. The ferric iron is insoluble and precipitates as a rust-colored deposit. Once the bacteria cells decay, they release a reddish or brownish slime that has the appearance of petroleum. Petroleum contamination is unlikely in most natural seepage areas, but you can confirm that the oily sheen is from bacteria and not petroleum by pushing on this layer with a stick. If it breaks apart, it is caused by iron bacteria.

Iron bacteria showing up as an oily, orangeish deposit. Photo by Pat Trochlell

29 October 2020

Native plant foliage has largely fallen or changed color, but several non-native plants are still green. This makes searching for them very easy if you’re intent on controlling them. This is especially true of common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) and non-native bush-honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.). Staying green when other plants have senesced and dropped their leaves gives these invasive plants an advantage over native species. Both buckthorn and honeysuckle have wide ecological habitat ranges, tolerating both wetland and upland conditions. Both species can dominate the landscape, shading out native species. Buckthorn is also allelopathic, creating soil conditions that suppress native vegetation and reduce habitat.

For those of us who want to rid our natural areas of these non-native species, a great way to remove them is pulling them up, roots and all. While this may give us a good feeling, it’s limited to small plants only. For large plants or large infestations, herbicides are usually required. One great source of information on controlling invasive plants is the Midwest Invasive Plant Control Network (MIPN) Invasive Plant Control Database. This database is a great tool to determine the most effective means of invasive plant control. It contains information gathered from both the scientific literature and the opinions of experts. You can search for a particular species and indicate the habitat, season, and whether you are a novice or expert. The search results can give you information on different means of treatment and the short and long-term effectiveness of those treatments.

We can’t control invasive plants everywhere, but we can work toward this goal on the properties that we manage and where we volunteer. Every invasive plant you remove can help, and this may eventually result in a fall landscape without a green understory.

by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Oct 30, 2020 | News

Landowner Services Coordinator Dan Carter writes about some special moments from the highly successful first year of TPE’s Landowner Services program.

Dan’s schedule for 2021 is almost full. Email landowners@theprairieenthusiasts.org as soon as possible to discuss a visit to your property.

For each of us in our own way, it’s been a tough year. We’ve shelved the activities we love, seen less of the people we care most about, and suffered loss. The future seems more uncertain and the world less recognizable. That’s why getting out and visiting landowners this season has been such a privilege. The wild has never been a more important sanctuary. Each visit has been a reminder that there are people out there with whom we share values, who are doing what they can to carry forward our natural and cultural heritage. The successes are moving, and the challenges are sobering. We have community in the prairie. And there is room for that community to grow.

I was unsure early on how much interest there would be in the Landowner Services program, but the work picked up quickly. Between late May and mid-October, I visited 66 properties belonging to private landowners in three states and in every chapter’s domain. My goal was 50!

The Bennett property in central Wisconsin. Photo by Dan Carter

Visit content was extremely varied. Some landowners are considering new prairie plantings; others are restoring (or considering restoring) existing prairies, oak savannas, oak woodlands, sedge meadows, or fens. Many properties have yielded new discoveries, both good and bad. For just about everyone, though, invasive alien species and aggressive native species are burdens. Getting enough fire on the land is also an obstacle.

This summer, I shared some of my early travels on TPE’s blog. There have been more since that time than I have room to share, but here are a few highlights from various corners of TPE.

In mid-July, I visited Kurt Peters and Elizabeth Hopp-Peters at their property in far western Green County, Wis. The main focus of that visit was the ongoing conversion of a sandy old field into prairie and the restoration of some black oak woodland and savanna. As I walked the perimeter of the old field, an interesting plant caught my attention between the path and the woodland edge. It turned out to be hairy pinweed, a special concern species with only one other known occurrence in the state. This plant, though it may look nondescript, is among the rarest native plants in Wisconsin. The only other known occurrence in the state is in Iowa County.

Historically, the woodland adjacent to the old field had been an open savanna or barrens. The hairy pinweed presumably happened to have been among the species that managed to colonize the edge of the old field before the savanna canopy closed and brush moved in. Other remnant vegetation included goat’s-rue, narrow-leaved pinweed, bird’s-foot violet, and hoary frostweed.

Hairy pinweed. Photo by Dan Carter

Hairy pinweed. Photo by Dan Carter

In September, I visited Barb and Dan Le Duc, who have a somewhat similar property in Eau Claire County, Wis. They’re also working to augment the diversity of a sandy old field next to a Hill’s oak woodland. The old field had been colonized by many interesting native species including fork-tip three-awn grass, narrow-leaved pinweed, hoary frostweed, Great Plains sand sedge, and rock spikemoss.

In late July I went to Brad Gaard’s property near New Ulm, Minn. The main foci of the visit were some existing and planned conservation plantings, but the highlight for me was a small bluff-top bur oak woodland above the Cottonwood River. There, an abundance of hairy meadow-parsnip (state special concern) grew at its northern range limit at the top of the bluff. The woodland also supported some particularly nice grass species, including black-seeded ricegrass and long-awned wood grass (farther southwest than any documented occurrences in the state).

A fruiting hairy meadow-parsnip. Photo by Dan Carter

A fruiting hairy meadow-parsnip. Photo by Dan Carter

Among my last several visits was the Dale and Kim Karow property near Fort Atkinson, Wis., well-known for its exceptional remnant prairie, calcareous fen, and sedge meadow communities. (See the forthcoming issue of The Prairie Promoter to learn about Kim Karow’s legacy of stewardship.) Despite being a well-botanized property, the site offered up several new finds including new county records of Greene’s rush and large path rush, both firsts for me. And as I walked the site with Walter Mirk and Dale, there were four kinds of gentian blooming: greater fringed, lesser fringed, stiff, and bottle. Several dozen Great Plains lady’s-tress orchids were also in flower. These orchids typically flower in late September and have corolla lips flushed with yellow (variable), with lateral sepals spreading and curving upward. They are leafless when flowering, and have bracts that usually overlap on the upper stem.

Great Plains lady’s-tress orchid. Photo by Dan Carter

My other photos are from Laurel and Alan Bennett’s property in Marquette County, Wis. (where they have successfully controlled reed canary grass in lower areas using Craig Annen’s systems approach, which in this case involved grass-selective herbicide and burning) and the Brian and Sheila Schils property in Pierce County, Wis.

If you’re considering a new project or simply want to walk and talk about your property, email landowners@theprairieenthusiasts.org soon to schedule a visit. My schedule for next year is already about one-third filled. In your initial email, include a little bit of background and location information for your site. Also, if you have success stories dealing with common problems like brambles, Canada or tall goldenrod, warm-season grass dominance, and the many varieties of invasive species, accounts of your successes would be welcome. Published science informs a lot of restoration and management, but anecdotes are where much of our collective knowledge resides.

Take care this fall and winter, get outside, and kill as much invasive woody vegetation as possible.

Above: In late September I visited Brian and Sheila Schils. We were joined by Abby Mueller, intern with the St. Croix Valley Chapter. The Schils’ bur oak woodland has been impeccably prepared for seeding by cutting and treating buckthorn throughout. Photo by Dan Carter

by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Oct 29, 2020 | News

This article was a collaboration with Rich Henderson.

We in the Empire-Sauk Chapter are dreaming of a day when more red-headed woodpeckers, regal fritillaries, and other grassland- and savanna-loving species will use Schurch-Thomson Prairie. That dream is one step closer now, as 25 acres around the Schurch-Thomson barn have been freed from a Managed Forest Law contract.

Woods in a sea of grass at Schurch-Thomson. Photo by Eric Preston

After many years of waiting, we’re now able to undertake the tree and brush removal that was prohibited by the contract. This is a crucial step for prairie and oak savanna restoration at this site, which is part of the Mounds View Grassland Preserve. Finally, the work has begun — and what a transformation!

In late August, with the generous loan of a forestry mower from The Nature Conservancy, we started clearing dense brush from the area. The next step was to harvest the larger walnut trees for sale. We engaged the services of Adaptive Restoration (located in nearby Mount Horeb), who brought their team of draft horses to the property. Rosebud and Duchess worked hard, providing excellent photo opportunities for at least one TPE volunteer.

Horse power. Photo by Eric Preston

The remaining walnuts under 12” in diameter, and some other non-oak species of all sizes, will be removed. We plan to give them away for firewood or small-dimension lumber over the winter, then pile and burn the tops. This will clear the way for follow-up brush and weed control. Next fall, we’ll seed in prairie and savanna species. The profits from the timber harvest will most likely pay for this follow-up work. However, the more work can be accomplished by volunteers, the more land management projects at Schurch-Thomson can be covered by the income.

If you would like to help clear the tree-tops and remaining trees, sign up for the Empire-Sauk Chapter’s weekly email notices (email empiresauk@charter.net). Look for work party announcements there and in the work party flyer on our webpage. Also, if you’re in need of firewood or free logs for lumber, or know someone who is, contact site steward Rich Henderson (608-845-7065, tpe.rhenderson@tds.net).

Soon, visitors to Mounds View will once again be able to appreciate the grandiose oaks that have been here for over 150 years.

Red-headed woodpecker in an oak savanna. Photo by Eric Preston

by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Oct 14, 2020 | News

Incoming TPE Executive Director Debra Behrens tells the story of her journey into her new role.

Debra wrote this additional greeting for our newsletter, The Prairie Promoter:

It started as a wish. As a child visiting my grandparents in rural Minnesota, I fell in love with the vast prairie skies and the steady hum of insects on summer nights. Only later did I realize that this place filled with wonder had long since lost the complex beauty that once thrived there. This growing awareness gave me a sense of responsibility to do what I could to heal the land. But finding an answer to the question of what I can do has been a 20-year journey.

The actual seed of an idea wasn’t formed until I met my husband and realized we shared the same dream: to become stewards of the land. We nurtured our seed along through the lean early years of our marriage until we were able to afford a small homestead near Viroqua.

We thought we had achieved our goal, but as part-time residents we weren’t making much progress. And it was becoming harder and harder to leave the beauty and tranquility of our rural home to return to the city for work. We resolved to find a way to make this our permanent home and spent the next year rearranging our lives to make that possible.

I first discovered TPE while researching what to do about our problem with wild parsnip. I followed your progress through the years with interest. When the Landowner Services program was announced, we reached out to Dan immediately for advice on the projects we were finally ready to undertake on our land. Then I saw your job posting for an Executive Director, and my heart skipped a beat. Here it was: my ideal job! The more I learned, the more I became convinced that my 20-year career in nonprofit development, combined with my values and my connection to this mission, were a match.

You have built a strong organization, and you have the ability to grow. Some of the most rewarding work I’ve done involved helping nonprofits through the next phase in their organizational growth. I’ve developed an entrepreneurial approach to solving problems, focusing collective energy, and building momentum. Together, we’ll pursue strategies that improve our overall health and viability so that what we leave for those coming after us is a thriving organization.

It all starts with having clear goals. We will need to work together to define what we want for our future. This is a grassroots organization, with all the beauty and messiness that entails. We won’t always agree, but we need to be willing to trust one another and commit to pursuing our strategic goals together.

There is much to learn. In the coming weeks and months, I will be reaching out to gather your stories, ideas, and advice. But please feel free to share your suggestions at any time. There will be challenges ahead, and we’ll be prepared to meet them through the strength of our commitment — not just to our mission, but to one another.

by The Prairie Enthusiasts | Sep 27, 2020 | News

It’s been 4 years since our chapter started the Species Conservation Project (SCP) in northwest Illinois (see the feature article in the March 2016 Prairie Promoter here), and in those years I have occasionally written about the rare plant gardens we started to help the SCP along.

Lonetree Farm’s rare plant garden beds. Photo by Rickie Rachuy

In my earlier articles, I mentioned the patience required when trying to duplicate what Mother Nature so willingly bestowed on us over the eons. I could not have known then what we all know now: a need to reach deep and summon the patience required to deal with a very changed world. Personally, I’ve been active outdoors in this time of isolation. The hubby, too, has become an excellent gardener. Together we now tend 117 native plant species in and around the two rare plant gardens here at Lonetree Farm.

We’ve learned a lot in the intervening years. Two important lessons are not to space plants too closely together (it’s hard to compost ‘extra’ seedlings when they’ve been lovingly nurtured under grow lights for months) and to hold back exuberant growth with stakes and chicken wire so other species don’t get smothered.

We pick seed from many of these plants, then overseed onto suitable protected sites. But some species are still coming into their own. The rarest of the rare we are tending include Cirsium hillii (Hill’s thistle), Dalea foliosa (leafy prairie-clover), Lespedeza virginica (slender bushclover), Lithospermum incisum (fringed puccoon), Lonicera reticulatum (yellow grape honeysuckle), Pediomelum esculentum (breadroot or prairie turnip), and Penstemon calycosus (calico false foxglove). Each has its own quirks and its own story.

Cirsium hillii: Cirsium derives from the Greek word kirsos, meaning “swollen vein”. Thistles were used as a remedy against swollen veins. The species epithet hillii is in honor of Ellsworth Jerome Hill (1833-1917), an American botanist and Presbyterian minister.

Cirsium hillii. Photo by Rickie Rachuy

Dalea foliosa: Dalea is a genus of flowering plants in the pea family, Fabaceae. Members of the genus are commonly known as prairie-clover. Its name honors English apothecary Samuel Dale (1659-1739). Foliosa means “leafy”. This is one of the rarest plants in North America.

Dalea foliosa. Photo by Rickie Rachuy

Lespedeza virginica: Lespedeza is derived from a mistaken reading of the name of an early Spanish governor of Florida — Vicente Manuel de Céspedes — by André Michaux, a French botanist and explorer. The specific name virginica refers to the Colony of Virginia.

Lespedeza virginica. Photo by Rickie Rachuy

Hairy pinweed. Photo by Dan Carter

Hairy pinweed. Photo by Dan Carter A fruiting hairy meadow-parsnip. Photo by Dan Carter

A fruiting hairy meadow-parsnip. Photo by Dan Carter