Karrikins & Soil Health: Emerging Tools for Accelerating Prairie Succession

Karrikins and Soil Health: Emerging Tools for Accelerating Prairie Succession

Article and photo by Brent J. Anderson, Minnesota Oak Savanna Chapter member

January 26, 2026

Prairie restorations often fall short of public expectations, not because of a lack of planning or care, but because the soil itself isn’t yet ready to support the species people hope to see in the first few years. “Patience is a virtue” reminders too often aren’t heard when the photos and plans suggest immediate gratification and beautiful outcomes. Early successional plants like black-eyed Susan and wild bergamot are always encouraging, but most audiences want richer diversity sooner than the traditional restoration timeline allows. Standard practices emphasize soil preparation, planting and weed management – then we wait for nutrient cycling, soil structure and mycorrhizal networks to mature enough for late-successional species to thrive. Depending on conditions and disturbance, that process can take 10 to 25 years.

Over the past four years, my interest in soil ecology has deepened, leading me to explore natural, largely native amendments that might promote earlier germination of a wider range of species. As I learned more about the chemical and biological signals within soil, I became especially intrigued by compounds associated with fire—particularly karrikins.

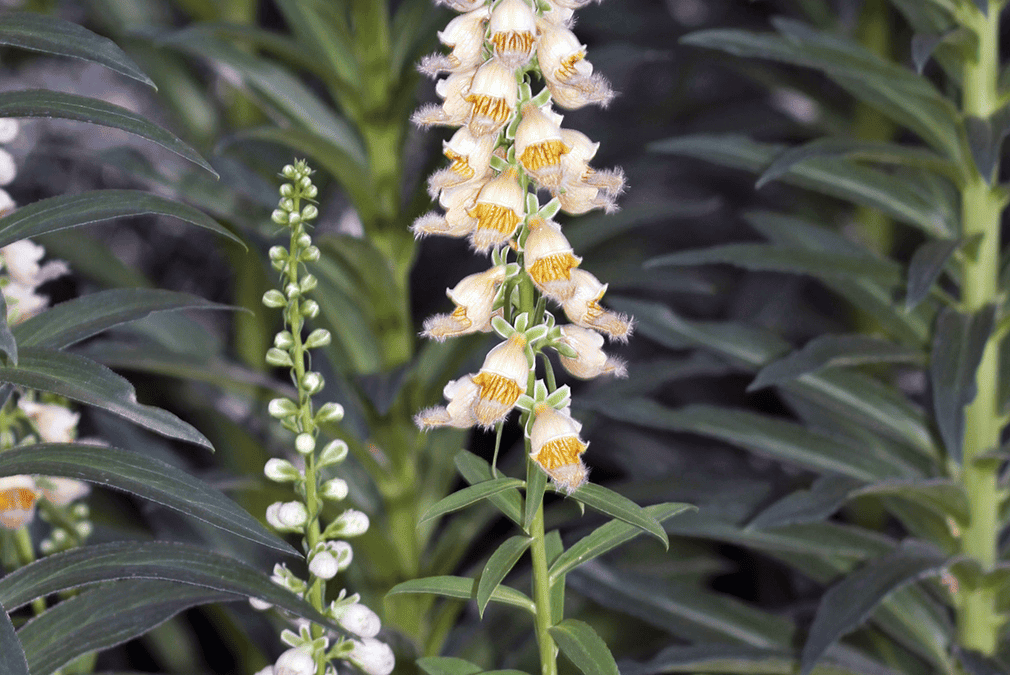

Karrikins were first identified in 2004 when Australian researchers isolated karrikinolide from the smoke of burned vegetation. These small organic molecules help explain why “smoke water” can stimulate dormant seeds and why fire-dependent species emerge so dramatically after wildfires or prescribed burns. In many ecosystems – including Midwestern prairies – certain species germinate only when fire releases karrikins that bind to soil particles and are later washed into the seed bank by rainfall. This is why plants like sundial lupine (Lupinus perennis) often appear only after several burns, and why some late-successional species remain hidden in restorations for a decade or more.

Plants that rely on this cue – often called fire-followers or fire-ephemerals – germinate rapidly after fire, grow, flower and set seed within a short window, leaving behind a new generation of dormant seeds in the seed bank. Rain alone cannot activate them. Without the chemical signature of fire, they remain dormant through many cycles of wetting and drying and may persist in the soil for decades.

However, emerging research also shows that karrikins are not a universal or unlimited solution. Concentration matters. While low levels of smoke-derived compounds can stimulate germination in some species, higher concentrations may actually delay or suppress germination in others. This variability suggests that prairie species respond differently to smoke cues, reinforcing the need for species-specific research rather than blanket applications. In other words, what “wakes up” one plant may tell another to remain dormant. Understanding these thresholds is critical if smoke-derived treatments are to be used responsibly and effectively in larger restorations or even small-scale projects.

For the “pocket prairie enthusiast,” smoke water is relatively simple to conceptualize, though it should be approached thoughtfully. Smoke water is typically made by capturing smoke from burning native plant material and dissolving those smoke compounds into water – essentially transferring fire’s chemical signal without applying heat to the soil. Importantly, any burned material should consist only of locally native grasses and wildflowers, free from treated lumber, invasive species or other contaminants. Using inappropriate plant material risks introducing unfamiliar chemical signals or residues that don’t belong in the ecosystem being restored. As with fire itself, restraint and ecological context matter.

Understanding these processes has meaningful implications for prairie restoration. If we can ethically and ecologically mimic or supplement natural fire cues – while respecting species-specific responses – we may be able to stimulate the emergence of plants that would otherwise take much longer to appear. Done carefully, this approach has the potential to advance prairie maturity without bypassing the natural checks that make these systems resilient.

Additional Research & Reading

- “What are Karrikins and How Were They ‘Discovered’ by Plants?” https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12915-015-0219-0

- “An Effective System to Produce Smoke Solutions from Dried Plant Tissue for Seed Germination Studies” https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4103107/

- “Karrikinolide1 (KAR1), a Bioactive Compound from Smoke” https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/13/15/2096

- “Using Smoke-water and Cold-moist Stratification to Improve Germination of Native Prairie Species” https://www.jstor.org/stable/26524807?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference

About The Prairie Enthusiasts and the Minnesota Oak Savanna Chapter

Established in 2024, this new Chapter covers the counties of Anoka, Carver, Dakota, Hennepin, Isanti, Ramsey, Scott, Sherburne and Wright Counties in Minnesota. We’re actively seeking passionate new members committed to the protection of prairie remnants, restoring degraded prairies, building new prairies and/or excited to learn more about prairie projects in their own communities. We invite you to subscribe to our Chapter updates and become a member. Learn more about the Minnesota Oak Savanna Chapter here.