Why Prairie Restorations Look Messy – At First

Why Prairie Restorations Look Messy – At First

Written by Brent J. Anderson, Minnesota Oak Savanna Chapter member

March 3, 2025

If you have ever stood at the edge of a newly planted prairie and thought, “This doesn’t look like much,” you’re not alone. I have heard it from landowners, neighbors and volunteers – and I’ve said it myself. The first year or two after a prairie planting can feel anticlimactic, even discouraging. Photos and seed mixes promise color, movement and diversity. What shows up instead often looks uneven, weedy or unfinished.

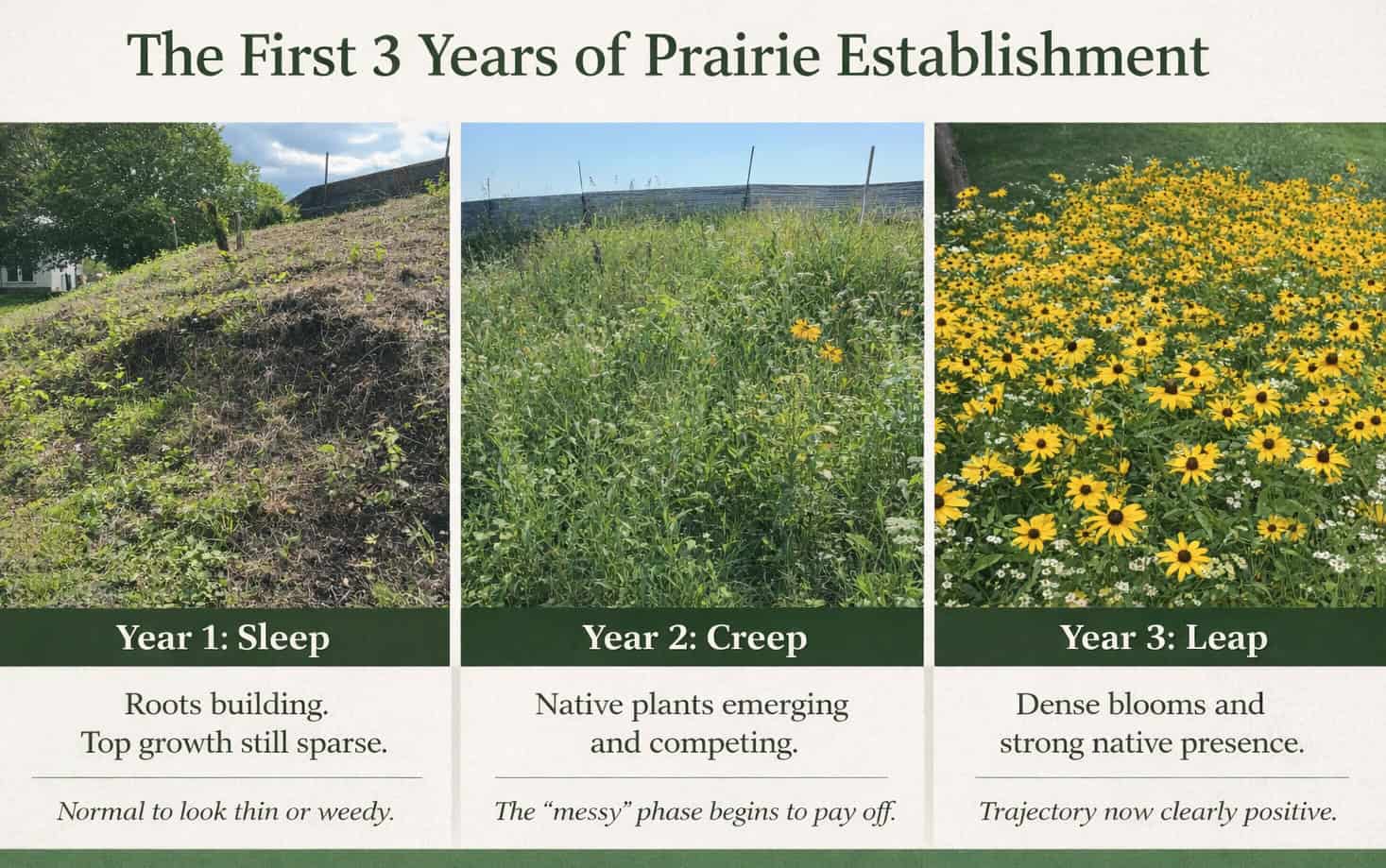

Among prairie restoration professionals, there is an old adage used to level-set expectations: “First year they sleep, second year they creep, third year they leap.” Experts know this rhythm well. Most newcomers do not – and that is understandable. We are used to landscapes responding quickly to effort. Prairies operate on a different timeline, and that early “messy” phase is not a sign of failure. It is a sign the system is getting to work.

One of the hardest mental shifts for people new to prairie restoration is realizing prairies are not gardens. They are not designed for immediate visual payoff. In the early years, the priority is not flowers – it is roots. Native prairie plants invest heavily below ground, building deep, resilient root systems that anchor soil, improve water movement and support microbial life. What we see above ground represents only a small portion of what is actually happening.

That is also why so-called “weeds” often dominate early on. Disturbed soils invite opportunistic plants responding to open space and sunlight. While no one wants invasive species to take over, the presence of certain early plants is not automatically a problem. Some have aggressive or deep roots that help break up compacted or clay-heavy soils, improving structure and water infiltration. In many cases, they act as temporary placeholders, occupying space while slower-growing prairie species establish themselves.

Management during this phase is important, but it often looks different than people expect. One of the most common and effective tools is mowing – especially during the cool season, when non-native plants thrive and grow fastest (overnight temps are below 70F – May and June). Early mowing helps prevent fast-growing non-natives from shading out young prairie seedlings that are still finding their footing. Typically, mowing continues through spring and early summer. After that point, non-native species mostly slow down and native plants can grow past them, and begin to take a competitive advantage. While most mowing efforts can lessen in July and August, it’s important to monitor the height of non-native species (e.g., Canada thistle and velvet leaf) and address out-competing stands as necessary. For smaller plots, I like to use a weed whacker or even a scissors to slowly move through the site and discover newly germinated species or get pics of bees and butterflies.

A simple rule of thumb many practitioners use is this: When non-native plants reach about 12 inches tall, mow or weed whack them back to roughly 6 to 8 inches. This practice stunts cool-season weeds without harming young native prairie plants intended for long-term establishment. Native prairie plants are also sensitive to cutting, but are often shorter in stature (especially year 1 and 2) during the cool season. For best results, it is generally wise to never trim closer than about 5 inches tall.

For small “pocket prairies” in backyards or front yards, weed whipping can be just as effective – and often more practical – than mowing. The goal is the same: reduce competition and light blockage, not create a manicured appearance. Used thoughtfully, these tools are not about “cleaning things up.” They are about guiding competition during a vulnerable stage.

Another common concern for newcomers is dead plant material left behind after a growing season. To many observers, it looks untidy or neglected. Ecologically, it is anything but. Standing stems and fallen leaves protect the soil surface, moderate temperature extremes and reduce erosion. As that material breaks down, it feeds soil organisms – bacteria, fungi and other microbes – that drive nutrient cycling. This quiet exchange between plants and soil is foundational to prairie health, even if it is not immediately visible.

I remember visiting an early restoration site a few years ago with someone who expected something closer to a wildflower postcard. What they saw instead was patchy growth, seed heads from the previous year and plenty of bare ground. We stood there for a moment before they finally said, “So … I’m not loving it. Is this the way it’s supposed to look?”

A year later, we walked the same site again. New species had appeared. The ground felt firmer underfoot. The prairie had not transformed overnight, but it had clearly turned a corner.

Prairie restorations reward patience because they are doing long-term work. In those early years, ecosystems are being rebuilt from the ground up – literally. Roots grow deeper, soil communities diversify and the seed bank begins to develop. Diversity comes later, once the foundation can support it.

Learning to read a prairie means learning to see beyond aesthetics. Messy does not mean broken. Sparse does not mean unsuccessful. Often, it means the system is doing exactly what it should. By the time a prairie begins to “leap,” much of the most important work has already happened, unseen.

If we can adjust our expectations and trust the process, we give prairies the time they need to become what they are meant to be: resilient, diverse and alive in ways that do not always announce themselves right away.

Minnesota Oak Savanna Chapter of The Prairie Enthusiasts

Our chapter includes the Minnesota counties of Anoka, Carver, Dakota, Hennepin, Isanti, Ramsey, Scott, Sherburne and Wright Counties. While our chapter prioritizes identification and management of remnant fire-dependent systems, many times we’re actively involved in restoration work – especially in creating buffers around existing remnants, or assisting landowners committed to re-creating prairies on their properties. We’re actively seeking new members committed to the protection and care of prairie remnants, managing prairies through prescribed fire, restoring degraded prairies, building new prairies and/or excited to learn about prairie projects in their own communities. We invite you to subscribe to our Chapter updates and become a member. Learn more about the Minnesota Oak Savanna Chapter here.

About The Prairie Enthusiasts

The Prairie Enthusiasts is an accredited land trust that seeks to ensure the perpetuation and recovery of prairie, oak savanna, and other fire-dependent ecosystems of the Upper Midwest through protection, management, restoration, and education. In doing so, they strive to work openly and cooperatively with private landowners and other private and public conservation groups. Their management and stewardship centers on high-quality remnants, which contain nearly all the components of endangered prairie communities.