Paying Attention to the Season During Restoration Work

Paying Attention to the Season During Restoration Work

By Jim Rogala

October 3, 2023

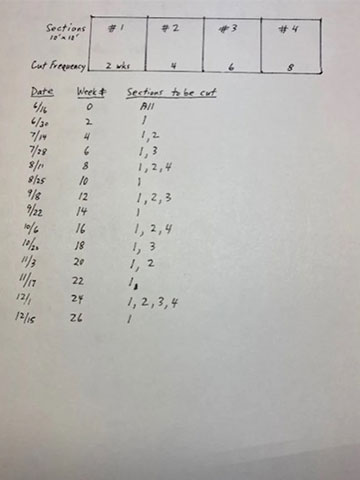

Prairie restoration land managers, whether landowners or those working on public or protected lands, typically have long lists of management needs. I’m no exception. My list contains many lifetimes of work I could do, so I prioritize tasks and tackle urgent needs first. These are typically long-range plans that span years and even decades. However, there is another component to selecting which task to work on at a shorter time scale: seasons of the year.

I’ve always had this seasonal aspect of restoration in my mind, but that is not very conducive to sharing it with others. As a past member of The Prairie Enthusiasts Education Committee, I proposed doing a simple guide to formalize the seasonal aspect of prairie restoration.

There are many factors that contribute to selecting which time of the year someone might do a specific task. Some examples are:

Plant Physiology

The translocation of materials in plants can vary drastically by season, not only in the rate of movement but also the dominance of some movement over others across seasons. Also, there are times when most of the energy in a plant is above ground, and other times it is below ground.

Herbicide Efficacy

Herbicides have temperature ranges that are best suited for their effectiveness.

Preparation for Upcoming Tasks

Some tasks are simply preparing for other tasks. If the work is not done to meet the requirements of performing an upcoming task, then you may have to delay doing something for a year.

Snow Cover

The presence of snow is a good time for some tasks and not good for others.

Keeping such factors as these in mind, it becomes obvious that performing some restoration work is best done in a particular season. Some examples are:

-

-

-

- When cutting and treating trees and brush, consider the optimum season to best translocate the herbicide to the location of action. If it is too cold or too hot, and the translocation is slow. Oil-based herbicides also volatilize at high temperatures.

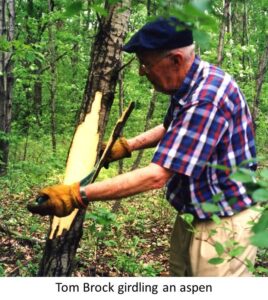

- For non-herbicide methods such as repeated cutting, summer is the preferred time because most of the energy stores are above ground. For clonal species, it is critical to not cut in fall or winter if you are not applying herbicide, as this will promote resprouting from nodes.

- Mowing firebreaks in preparation for a spring burn should be done before winter to minimize dry debris on the break.

- Brush pile burning is best done in the winter when there is snow on the ground.

-

-

The work of the Education Committee, with helpful reviews from our Science Advisory Group, yielded a document titled: Quick guide to restoration practices: Timeframes and general methods. We hope those that are doing restoration find the guide informative and useful in planning seasonal activities. And, as you might notice, there are no seasons with nothing to do!

This article appeared in the Fall 2023 edition of the Prairie Promoter, a publication of news, art and writing from The Prairie Enthusiasts community. Explore the full collection and learn how to submit your work here.